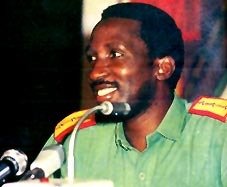

Captain Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara

This month, at the time of his birthday, Africa remembers Captain Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara (December 21, 1949 – October 15, 1987). He was the president of Burkina Faso (formerly Upper Volta) from 1983 to 1987.

As Africa looks desperately for leaders of integrity and vision, the life and ideals of the late Thomas Sankara seem more and more relevant and exemplary with the passage of time. Sankara is still venerated on his own continent as the ‘African Che,’ a legendary martyr like Patrice Lumumba or Amilcar Cabral.

His brief four-year rule and his revolutionary program for African self-reliance as a defiant alternative to the neo-liberal development strategies imposed on Africa by the West, still rings out today. Sankara is one of the most exceptional figures in the history of African liberation and a true visionary for Africa’s future.

Sankara, a charismatic army captain, came to power in Burkina Faso, in 1983, in a popularly supported coup. He immediately launched the most ambitious program for social and economic change ever attempted on the African continent. To symbolize this rebirth, he even renamed his country from the French colonial Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, ‘Land of Upright Men.’ As soon as he took office, he reduced the salaries of all public servants, including his own, and forbade the use of chauffeur-driven Mercedes and 1st class airline tickets. Like many revolutionary leaders, he banned unions, a free press, anything which might stand in the way of the immediate and radical transformation of society.

In the 1970s, Sankara became ideologically close to communism and the examples of the Cuban revolution and Jerry Rawlings in Ghana. As a commando trainer for the Alto Voltaire army, Sankara met Blaise Compaoré, with whom he would form the secret organization “Regroupement des Officiers Communistes” (ROC).

Sankara was appointed Secretary of State for Information of the military government installed in September 1981, but resigned on April 21, 1982 in opposition to the anti-worker drift of the government, which had just prohibited the right to strike and dismantled the main trade union of the country. A new coup, on November 7, 1982, brought Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo to power, and Sankara became his prime minister in January 1983, but resigned on May 17 and was arrested, along with other ROC leaders, under pressure from the French government. This provoked a popular uprising.

A Libyan-backed coup d’état made Sankara president on August 4, 1983, at the age of 33. With a potent combination of personal charisma and a social organization with democratic participation, his government brought initiatives against corruption, and improved education, agriculture, and the status of women, as well as combating the caste system and the traditional privileges of the tribal elites. His revolutionary program provoked strong opposition from the traditional leaders of the small but powerful middle class, as well as misgivings from France, as being against its neocolonial interests in Africa. In addition to friction with the more conservative members of the ruling junta, these actors led to his downfall and assassination in a bloody coup d’état on October 15, 1987. His successor was his onetime comrade, Compaoré.

Sankara was the first to recognize that key to the development of Burkina Faso and Africa was improving the status of women. He was the first African leader to appoint women to major cabinet positions and to recruit them actively for the military. He outlawed forced marriages and encouraged women to work outside the home and stay in school even if pregnant. He launched a nation-wide public health campaign vaccinating over 2 ½ million people in a week (Yellow Fever, Measles), a world record.

He was also one of the first African environmentalists, planting over 10 million trees to retain soil and halt the growing desertification of the Sahel. He promoted local cotton production and even required public servants to wear a traditional tunic, woven from Burkinabe cotton and sewn by Burkinabe craftsmen. He redistributed land from the feudal landlords and gave it directly to the peasants. Wheat production rose in just three years from 1700 kg per hectare to 3800 kg per hectare, making the country food self-sufficient. He started an ambitious road and rail building program to tie the nation together, eschewing any foreign aid by relying on his country’s greatest resource, the energy and commitment of its own people.

Sankara’s experiment attracted intense interest far beyond Burkina Faso, posing a serious threat to the status quo, especially to France’s continued dominance of its former West African colonies and to the corrupt regimes ruling these client states. Sankara spoke eloquently and unflinching in forums like the Organization of African Unity against continued neo-colonialist penetration of Africa through Western trade and finance. He opposed foreign aid, saying that ‘he who feeds you, controls you.’ Decades before talk of cancellation of Africa’s debt became acceptable in world banking circles, Sankara called for a united front of African nations to repudiate their foreign debt. He argued that the poor and exploited did not have an obligation to repay money to the rich and exploiting.

There were flaws and contradictions as Sankara followed a Bolshevikist revolutionary path. At this time, he was isolated and had no method to pattern on for his revolution. By 1986 Sankara’s rapid, sometimes authoritarian changes had begun to alienate larger sectors of the Burkinabe population, leaving him more isolated, even from elements in his own ruling circle. Like revolutionaries as far back as the French Revolution, Sankara was committed to achieving his ideals, but was unskilled at the time factor and did not give enough time for the changes to take root in the people. Yet, he was a beloved man, in among the people. There was a great recognition that he is working for the people. This is very similar to the Russian Bolsheviks, (Russian Communist Party of Bolsheviks) who refused to share power with other or even moderate the revolutionary drive.

As one close friend observes, ‘Sankara was an impatient man,’ driven by the desperation of his people. As opposition mounted, Sankara attempted to repress it. He established Peoples Revolutionary Tribunals in towns and workplaces around the country where people were tried without counsel for being corrupt officials, counter-revolutionaries or just lazy workers, based not on credible evidence just private grudges. He also encouraged the formation of Revolutionary Defense Committees, gangs of armed youth who terrorized ordinary citizens. When the nation’s school teachers went on strike, Sankara dismissed all of them, leaving the education system, his country’s greatest hope for progress, a shambles. Thomas Sankara became a theat to the neo-colonialists. To today it is a question whether his opposition were grassroots, or encouraged by France and France neo-colonialists in Africa.

By the beginning of 1987, Sankara’s position had become more precarious. He was warned to take action but fatalistically refused on the grounds that he needed to remain true to the ideals of his revolution. He noted prophetically that Che Guevara had been executed when he was 39 as well. Clandestinely, elements in the Burkinabe leadership forged relationships with Côte d’Ivoire president Félix Houphoet-Boigny, France’s staunchest ally and an outspoken opponent of Sankara’s increasingly influential attacks on neo-colonialism. On October 15th during a staff meeting, a gang of armed military, either led or ordered by Blaise Compaoré, Sankara’s closest friend and most trusted comrade throughout the revolution, assassinated him. His body was dismembered, buried in a make-shift grave and any mention of him was erased from public view. Twenty years later, Blaise Compaoré had remained dictator of Burkina Faso; he has become immensely wealthy and was France’s most reliable proxy in the region.

We recently posted an essay from Femi Akomolafe explaining how the French neo-colonialism is only now being dealt with in the Sahel and how ECOWAS, the sell-outs, will shrink. https://sovereignista.com/2024/12/22/10-days-to-ecowas-rupture/

Burkina Faso, the land of upright men is part of the three countries in the Sahel that is leading this charge. This is Sankara’s legacy.

Sankara was a proud and noble man. At the end, he was like so many other leaders with ability, simply done away with when the progress became real and the changes that he worked for became threatening to the colonialists.

Speech at the United Nations