Spotlight (Part 2) – The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Arctic maritime routes

With thanks to Nat South, the author

1st part: The Spotlight, Part 1 – The geopolitical and military Implications https://sovereignista.com/2023/03/10/spotlight-on-the-northern-sea-route-nato-the-us-and-china/

Abstract: The article discusses the Chinese government-led project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which aims to increase global economic interdependence and trade relations. However, the BRI has met resistance from the US and the EU, who view it as a threat to their national interests and global reach. The article also explores the conflict between Ukraine and Russia and how it has affected the BRI’s engagement in the region, particularly in Russia. The article also highlights some of the issues affecting geopolitical relations between the West and China, on how this affects the future development of BRI. One aspect outlined in the article is the potential role for maritime routes within the BRI infrastructure, in particular in the Arctic.

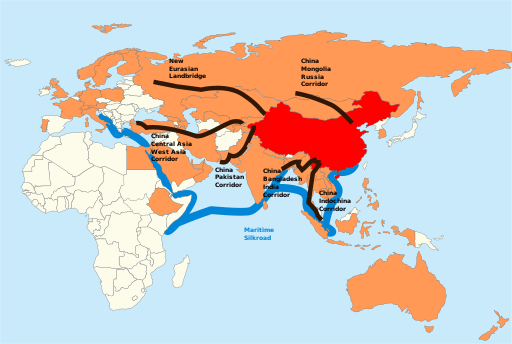

The BRI or the One Belt One Road, (OBOR), project is a Chinese government-led project that started in earnest in 2017 to increase global economic interdependence and trade relations, with emphasis on infrastructure development and investment project that seeks to build transportation and communication networks connecting Asia, Europe, and Africa. Yet it has met continued resistance, largely due to the U.S. efforts to hamper its global roll-out. Back in 2013, the BRI in its initial stages outlined two routes, one an overland route through the heart of Asia, (road and rail transport) and also a maritime route. It has two main components:

- the Silk Road Economic Belt, which focuses on land-based infrastructure projects, (SREB, in black)

- the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, which focuses on maritime infrastructure projects, (MSRI in blue).

The Eurasian overland routes go along six main corridors, these also branch off to various destinations along the links, to various transport nodes. A number of these corridors included Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus. The maritime element includes the Polar Silk Road, (PSR), which was developed by China in a White Paper in 2018.

Washington’s stance

Let’s face it, Washington continues to take a very dim view of both the BRI, the PSR, since the very existence of an alternative transport and trade infrastructure is seen as a potential threat to the U.S. national interests, to its global reach and of course, by default, a threat to NATO as well. NATO leaders back in 2018, made it clear that the BRI presents potential security implications particularly in areas of strategic importance to NATO, such as the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions. Later, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said in a speech (September 2020) where he expressed the fact that there are “concerns about the size of China, the technological advances of China, the size of the Chinese economy, soon the largest economy in the world, defence budgets, their new military capabilities. The size of China is of concern in the United States.” He added that “So, if anything, the rise of China makes NATO even more important for all of us, but especially for the United States.”[1] As the expression goes, it takes two to tango, since there is a very intimate symbiosis between the U.S. and NATO. A year later, Stoltenberg stated the following “At the same time, we need to also realise the security consequences of the rise of China, because China is a power that doesn’t share our values”. [2]

The U.S. has stated that countries need to be to be wary and consider the long-term implications of participating in BRI projects. The U.S. frequently accuses China of using debt-trap diplomacy, as well as seeing the BRI as potentially extending a Chinese military footprint. The hard long look in the mirror by Washington just isn’t attainable. “Bolton characterized China’s presence in Africa as predatory, opportunistic and power-hungry.” [VOA, December 2018]. In reality, Western multilateral financial institutions and commercial creditors hold most of the debt owed in Africa, accounting for 35%, [3] compared to Chinese debts owed, (12% coupled with a lower rate). Similarly, right on script, NATO leaders have at times expressed concern about the “lack of transparency, non-market-based practices, and the risk of indebtedness” associated with the BRI.

Washington sees it as a tool for China to extend its political influence and gain strategic advantages around the world, usurping decades long Euro-Atlantic hegemony. There are two very contrasting viewpoints: the U.S. sees military security as a key factor in foreign policy, China, on the other hand, greatly values economic security above all.

Outline of BRI corridors, transport nodes, [4] What is noticeable on the visual is the total lack of routes or nodes on the North American continent.

The BRI and the conflict between Ukraine and Russia

Taking a closer look at the BRI in Russia and Eurasia, Russia has been among the top beneficiaries of the BRI Chinese development spending up to 2021. Now this is down by 100%. [5]. The Russian Special Military Operation in Ukraine had a profound effect on the overall BRI engagement, as it was a significant geopolitical shock, that is still being felt, especially taking into consideration of energy price hikes. There is now also an increased pivot to the Middle East and Africa, with Saudi Arabia being one of the main beneficiaries of BRI investment last year.

Global trade has taken a turn for the worse in recent years, with positive signs now being just felt, which also impinges on the whole BRI financial infrastructure and also shapes China’s post-COVID outlook. There are several factors that curbed China’s keenness to continue heavily investing via the BRI in Russia. The conflict in Ukraine has proven to be highly problematic given the vision of the BRI includes the following pillars, Unimpeded Trade, Infrastructure Connectivity and Understanding between People. More specifically, US and EU sanctions have severely hampered any normalcy of trade, notably on the “gateway to Europe” corridor, the New Eurasian Land Bridge (NELB) corridor, the much-vaunted backbone of the Chinese European BRI route. It heavily relies on rail freight, with a reported pre-2022 figure of 90% of rail cargo using the NELB to ship goods to Europe.

Understandably, the importance of a peaceful gateway for trade is key to a successful realisation of the BRI. Thus, China has put some distance between Russia, due to the geoeconomics consequences of the conflict in Ukraine, as it has severely jeopardised Chinese trade routes as well as undermined a broad range of Beijing’s geopolitical interests. Despite this, it has to be stressed that China’s fundamental strategic outlook, has not changed, as evidenced by the visit of President Xi Jinping to Russia this week. Additionally, Beijing has taken onboard Moscow’s security concerns and has taken a dim view of both the U.S. and EU sanctions, as they had a negative impact on global trade and security.

Noticeably, strenuous efforts are being made by China to seek a peace deal and unveiled a 12-point peace roadmap, this is not reciprocated whatsoever by either the U.S. or Europe, as evidenced by the hard response of the White House [6], viewing any possible ceasefire brokered by China, as a potentially ‘bad deal’ for Ukraine, also seen by a media outlet as “Beijing’s effort to highlight Washington’s unreliability”. The hardliner stance of the U.S. and EU, along with a bitter cynicism on this relationship has no limits. Lastly, a consistent narrative is being shaped by Washington and Brussels on China’s perceived implicit support to Russia, the latest being claims made by US officials that Chinese ammunition has been used in Ukraine. This narrative effectively scuppers any intention to see China in a positive way.

https://twitter.com/globaltimesnews/status/1637741640646537216?s=20

Increasing US-instigated hostility towards China, especially through the decoupling efforts, aimed at derailing China’s increased influence, just isn’t conducive to continuing to substantially promote BRI engagements in the Euro-Atlantic region. Along with similar antagonism towards China being expressed at the highest levels in Europe, many of the BRI linked Chinese projects in Europe have already been cancelled or delayed indefinitely. The EU’s stance is unlikely to change in the short term or even medium-term for that matter.

Washington is persistently souring relationships in a drip-by-drip manner. None of which will lend to an enduring fruitful relationship being cultivated between the US, the EU and China. With doors being continuously slammed in the face of Chinese investment and projects, Beijing will eventually distance itself and increasingly pivot elsewhere, to the benefit of Central, South America, Africa, as it is already the case in the Middle East.

Bilaterally, there are lots of opportunities going forward between Russia and China, that sit outside of the BRI, but are equally significant, namely in trade, with parallel imports, (Russian LNG and oil are one example). Likewise, China is learning about the wide-ranging potential risks it could face from the West, should a raft of sanctions be imposed on China.

Taking a step back, it would be wrong to say that the BRI projects are no longer valid but need to be considered as being on hold regarding Russia for the foreseeable future. Yet, other trade associations and routes are being developed, in parallel to the BRI, notably, the creation of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), and the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) pushed by Russia, Iran, and India. Arguably, such initiatives will help to reconfigure the bulk of BRI engagement elsewhere. It can also be argued that in the long run, the potential synergy could fit into a more diffuse BRI network, by the fact that these are independent transport links and nodes, that might be key to circumventing Washington’s growing ambitions to strangle Chinese trade.

A broader image appears internationally, one where President Putin described as “multilateral structures such as the SCO and BRICS”, which will become more widely promoted and become more prominent globally. Part of this will be elements of the BRI, the EAEU, all of which setting the stage for a new era of multipolarity.

The maritime aspect

Since numerous spanners have been thrown into the works, the interconnectivity and efficiency of the BRI overland routes through Eurasia is in disarray, particularly through Russia and of course Ukraine, it is quite possible that the maritime routes, (MSRI & PSR) will slowly take on more importance on a longer time span, although at the moment, it is not clear how this will evolve.

Arctic shipping has gained increasing attention in recent years due to the use of the Arctic Northern Sea Route (NSR)”, (Северного морского пути), as an alternative shipping lane for Asian trade, and the potential benefits it could bring to global trade. China values the NSR as a key segment of the BRI [7], becoming more significant when the Polar Silk Road, (PSR), was subsequently developed. Notably, a significant proportion of this continued predicted increase in traffic growth along the NSR is due to the ongoing development & construction of Russian oil & LNG projects, resulting in cargo deliveries through the Russian Arctic to Asia, (more on this in a forthcoming article).

Most of the maritime portion designated in the BRI uses long-used conventional sea transportation routes, via the Suez Canal. Yet, both the BRI and the Polar Silk Road have provided the foundation for investments and increased cooperation between Russia and China in the Arctic, in particular the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation (AZRF). As part of the ongoing efforts by Russia to revitalise the AZRF, includes a new generation of icebreaker fleet being built, new ports being built and existing ports getting progressively modernised. The words of President Putin back in March 2018,[8] that the NSR will become “the key to the development of the Russian Arctic, the regions of the Far East”, is starting to take shape.

The use of the NSR along with Chinese investment will ultimately stand to provide an economic impetus to planning and creating infrastructure in the region. Although maritime trade is an important element, there are other areas that will be economically interesting. Consequently, China will want to get a foothold in the region, regardless of the current geopolitical turmoil.

This is especially noteworthy since EU and NATO member Arctic states had grown wary of any potential Chinese investment in their territories, since the authorities see potential ulterior motives, (whether it is economic entrapment, military encroachment, a threat to national security). A case in point was a Greenland mining licence given in 2021, that provoked a sharp response by Washington, [9]. The Russian controlled NSR and Arctic infrastructure will likely provide a less troublesome investment opportunity. However, this greatly depends on the fundamental reaction by EU and NATO members on maintaining trade relations.

A critical geopolitical juncture

Russia is at a crucial turning point, both economically and geopolitically, in a pivot, that the US Carter administration was adamant not to see, through the implementation of “the triangular diplomacy”, since it believed that such an alliance could pose a significant challenge to US interests and security, [10]

Regarding the goal of keeping China and the Soviet Union separate, National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski stated in a speech, on June 26, 1978, at the Asia Society in New York City.

“The triangular relationship must not become a triangle of hostility. It is essential that both the Soviet Union and China be convinced that neither the substance nor the rhetoric of our efforts to improve relations with the other is aimed against them.”

Department of State Bulletin, Vol. 78, No. 2012, July 1978, pp. 22-28.

That type of diplomacy is now well and truly dead and buried, amply helped by a succession of US administrations in the last decade. The world is moving once more into divided blocs, the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific bloc, (NATO, EU, AUKUS) versus the rest of the world. The BRI was initially meant to overcome antagonistic blocs being locked into an adversarial “Cold War II”, yet it will continue to exist, evolve and develop in other parts of the world. The old and new maritime routes will hopefully prove to be resilient and enduring, in maintaining global and regional trade.

[1] https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_178355.htm?selectedLocale=en

[2] https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_182812.htm?selectedLocale=en

[4] https://thediplomat.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/thediplomat_2022-03-17-193524.png

[5] https://greenfdc.org/china-belt-and-road-initiative-bri-investment-report-h1-2022/

[7] https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/zchj/qwfb/14216.htm

[8] http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/56957

[9] https://www.politico.eu/article/china-arctic-greenland-united-states/

In the discussion of Nat’s article before it was posted, Nat specifically mentioned that the part of the puzzle with Saudi Arabia and BRI is reaching clarity. I have this bookmarked to take a look at in depth, after the summit. Can any of you see this?. I’m so glad… Read more »

Hi Nat, welcome. I talked about this very Bolton quote, the Imperial attitude par excellence to push out any honest competitor from the Global South. The Trump regime brought a clarity and honesty not seen seen Truman or Bush II. It is sad how the West shoots itself in the head. Mindlessly… Read more »