Latin American Liberation Day : From political independence to debt peonage.

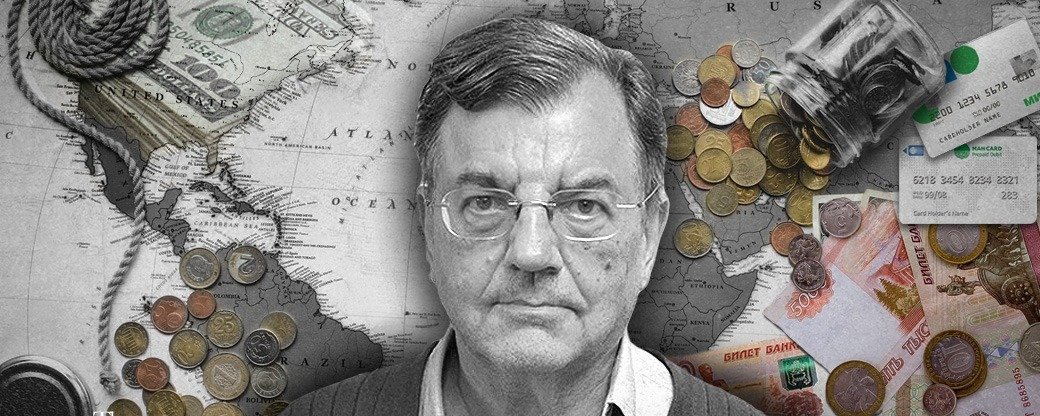

In relation to the piece that I posted on Daily Chronicles regarding Hispanic Heritage Month, and the list of countries that declared independence in the month of September 1821, Michael Hudson kindly participated by sending in the history of the financial sector, which is a chapter in his new book, ranging from the Crusades to WW I. After enjoying the idea of massive independence, Mexico, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and Chile, this may evoke sighs or tears.

—

Latin American liberation struggles open a new European credit market

Latin America’s movements for political independence and the abolition of slavery were sidetracked into one of the great tragedies of modern history. Slavery was indeed replaced, but was replaced by debt peonage on a national level, leading to impoverishment, underdevelopment, and a pattern of trade and debt dependency involving a loss of economic sovereignty – all of which still continue today.

Like other countries emerging from colonialism, those of Latin America felt obliged to borrow from European bankers in their attempt to create viable independent economies by modernizing their industry and basic infrastructure. But given the fact that no market had developed for international lending to governments other than for war financing, and the inherent risk of non-payment by debtor economies that were not yet financially viable, bankers imposed harsh terms. And Latin American countries had few resources to earn the money to pay the debts that they took on. The upshot was that their former colonial rulers were replaced by equally extractive bank consortia, and the slavery from which they sought to free their population was replaced by national debt peonage.

The borrowing terms set for Mexico, the second largest Latin American debtor after Brazil, show how lucrative the new “emerging market” bonds were for bankers, and how onerous their terms were for debtor countries. In 1824, Mexico’s main banker, B.A. Goldschmidt & Co., arranged the issue of bonds with a face value of £3.2 million and a 5% interest coupon. As was the usual practice to attract buyers, the bonds were issued at 58% of that price, a discount leaving just £1.85 million in proceeds. That increased Mexico’s effective interest rate to 8.6%, which was even higher after the banker deducted £750,000 in commissions and other fees, leaving Mexico with just £1.1 million.[1]

The inevitability of default was built into such arrangements from the outset, giving Europe’s financial powers a control over debtor countries that made their nominal political independence almost irrelevant. What triggered the first wave of defaults by Latin American and other countries was the London stock exchange’s own panic from December 1825 to spring 1826, triggering the first truly international financial crash. Twelve smaller British banks failed, leading the Bank of England and other major banks to freeze their lending. That cutback made credit unavailable to finance trade and hence the ability of nations to earn the revenue to pay their bondholders. Russian, Haitian and Greek bonds were affected, as well as those of Latin America.

In April 1826, Peru (owing £1.2 million) became the first Latin American country to default on a scheduled debt payment. But by July the panic had run its course. Prices for foreign bonds recovered as normalcy returned as “all of these borrowers renegotiated and settled their debt situation starting by the mid-1830s.”[2] In fact, there were no outright repudiations of official Latin American borrowings throughout the century as the continent’s debts held up better than most.

Historians of debt have noted that “the colonial wars and foreign control commissions that could be observed in Southern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East were seldom seen in Latin America.” [3] But in addition to France’s military intervention in Haiti to enforce collection of reparations debt (discussed below), it intervened in Mexico to oppose what stands as really the first claim for debt repudiation based on what came to be called the “odious debt” principle (also described below). When Mexicans elected Benito Juarez president in 1861, the Conservative oligarchy embarked on a civil war to overthrow him. Its leaders borrowed from the Swiss bank Jecker and Company to finance the fight, and seized a deposit earmarked to pay British holders of Mexican bonds. But the Republicans overthrew the Conservatives in the ensuing Reform War, and Juarez refused to pay the debts the Conservatives had taken on when illegitimately claiming to represent Mexico.[4]

Demanding some 60 million francs in respect of the Jecker bonds and other debts, France got Britain as well as Spain to join it in signing the Convention of London treaty in autumn 1861 backing a war to extract payment. Britain and Spain, however, decided to avoid the risk of armed conflict with the United States by leaving France to fight by itself. In 1862, France’s Emperor Napoleon III (ruled 1852-1878) embarked on a six-year war to install the Habsburg Archduke Maximilian as Mexico’s monarch. But the pretender lost and was shot by a firing squad in 1867, and Juarez was restored to the presidency. The United States backed his policy of driving foreign powers out of the Western Hemisphere. Indeed, it had helped Juarez arrange an estimated $18 million financing for the arms used by his troops. But Mexico’s economy remained so debt-burdened and economically polarized that social revolution continued throughout the remainder of the century.

—

[1] The 58% rate seems to have been typical. Toussaint, “How Debt and Free Trade Subordinated Independent Latin America,” https://www.cadtm.org/spip.php?page=imprimer&id_article=13665, June 28, 2016, walks readers through the technicalities. After paying £0.5 million in interest between 1824 and 1831, Mexico “still had to pay at least £6 million in principal and interest,” draining its resources and crippling its ability to pay.

[2] della Paolera and Taylor, Sovereign Debt:29 and Triner, “Emerging financial markets”:14-17. Goldschmidt had been one of the first banks to fail already in December 1825, but for bad domestic loans, not those to Mexico.

[3] Juan Flores Zendejas and Felipe Ford Cole, “Sovereignty and Debt in Nineteenth-Century Latin America,” March 2021:49-72, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198866350.003.0003.

[4] William Wynne, State Insolvency and Foreign Bondholders. Selected Case Histories of Governmental Foreign Bond Defaults and Debt Readjustments, vol. 2 (New Haven, 1951), describes the corrupt self-dealing behind the Jecker loan and other French claims. It was a model of European creditor practice.

“The inevitability of default was built into such arrangements from the outset … that made their nominal political independence almost irrelevant.”

☝️👇🏽☝️👇🏽☝️👇🏽

everybody knows Michael Hudson is a genius, having the privilege of reading or listening to him is like gazing upon Winged Victory or David for the first time. every time. history is fortunate to have been gifted such perspicacity as michael’s to bear witness to the creation & implementation of… Read more »