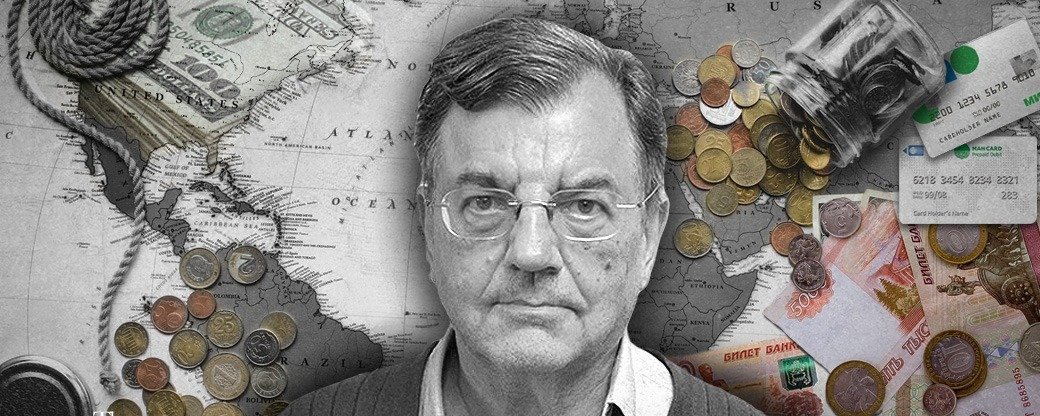

Michael Hudson: The New Civilizational Divide: Rentier Empire vs Productive Economy

With Glenn Diesen

GLENN DIESEN: Welcome back. We are joined today by Professor Michael Hudson to discuss the direction of civilization. So thank you very much for coming back on.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, thanks for having me again, Glenn.

GLENN DIESEN: So I’m thinking when we assess the economic, political, and social condition today, I can’t help but feel that we’re no longer at the peak of civilization. And you, of course, have written a book in the past with the title The Destiny of Civilization: Finance, Capitalism, Industrial Capitalism, or Socialism. And I’m thinking there must be a lot of new material for your book now if you wanted to do a remake. But I thought overall a good place that we could start is how do you link the economic system to the rise and fall of civilization? And what are the economic indicators of civilizational decline?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, I’m not going to write a remake, but I will make a sequel. And the sequel goes back in time to really review what classical political economy was all about and why classical economics was really the plan for industrial capitalism. And so I have to review some economic theory here because there is a great difference between the decline of an economy or an economic system as we’re seeing today and the decline of a whole civilization. Even though there’s called as a civilizational conflict between today’s finance, rentier capitalism in the West and the industrial capitalism with Chinese characteristics, which is amazingly like the American protectionist characteristics and the British characteristics under David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill and the German characteristics.

All of the industrial societies and the whole takeoff of what we think of as our civilization is actually a transformation of the economy itself. And the takeoff of industrial capitalism was really in Britain. And I think if we look at what they thought the course of industrial capitalism and the civilization and the world that they were going to dominate was all about, that’ll set the stage for what went wrong and why haven’t we achieved what all of the classical economists were expecting for industrial capitalism to develop a mixed economy, public, private, with rising government spending on infrastructure to keep the cost low, and especially to do the one thing that was revolutionary in industrial capitalism. And that was to get free of feudalism and get free of the legacies of feudalism. And the major legacy was the hereditary landlord class that still dominated the House of Lords and wanted to protect the land rents of the landed aristocracy, mainly in their agricultural lands.

Real estate rents and housing rents hadn’t really taken off yet, but the big problem that faced Britain was how to feed the population in the face of this protectionist landlord class. And Ricardo in 1817 explained what threatened to block the takeoff of British industry, and at least to bring its expansion to a halt, was the need to employ labor to produce commodities, to sell at a markup. And ultimately, the end of these, most of these products, according to Ricardo, as labor theory of value, the price and value of them was reducible to labor. And that included the labor that was embodied in the machinery that industrialists used, as well as to produce the food and the other products that labor had to pay for out of its wages.

Well, employers had to pay high enough wages to cover the cost of subsistence. And because well-educated and well-clothed and healthy labor that was well-fed was more productive, these costs had to be covered by the employer. Well, the aim of the industrial capitalist, therefore, was to reduce the costs of consumption needed by labor in order for employers to hire it. And the most pressing cost of his day, certainly the most pressing rising cost of Ricardo’s day, was the rising price of food that resulted from the Corn Laws, the tariffs on food imports that prevented free trade in food.

Britain in 1815 had emerged from the Napoleonic Wars that had isolated Britain. And as a result, Britain had to depend on its own landlords, its own land to feed itself. And as soon as foreign trade began after the return to peace, the landlord said, well, our rents are going down. You have to protect them by imposing tariffs on them. And that prevented British employers from being able to import lower-priced food to feed their labor so that they didn’t have to pay such high wages. [When I say this], I think of the parallels with the modern economy, which I’ll get into. The landlords demanded land rent.

And so the fight for 30 years from 1815 to the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 was for free trade. And the fight for free trade, that was the first step in overcoming the landlord’s resistance, saying the economy for us is all about land rent, not for industrial profits. We don’t care about industry, we just want our rents. And Ricardo gave the explanation for what would happen if you lent, if you permitted the economy to turn into a rentier economy, paying its rents to landlords, first for food, and in time for housing, for land rents for housing. And later economists of the 19th century said, well, it’s the same thing with monopoly rents. We don’t want monopolies because that’ll increase the cost of living and doing business. And then finally, at the end, they said, well, you know, the biggest payment of rent, rentier income at all, is to the creditors, to the bankers, and the bondholders in the form of interest and financial fees.

And so, the role of industrial capitalism in all these countries was to minimize these three classes: the landlord and raw materials-producing owning classes, the monopolists and the banking classes. And that’s what made industrial capitalism so successful in countries that were undergoing these reforms. Because in countries that didn’t have the reforms, because the landlords were powerful enough to block free trade, to block taxation of their rental income, and to block governments from minimizing rents to streamline the economies and cut the costs of living and doing business, they were going to be left behind.

So, what Ricardo did was formulate classical value theory, which said value is produced by labor, and the, but prices don’t reflect this value. Prices are much higher than this value, and the excess of prices over value was economic rent. And that rent is unearned income. John Stuart Mill said that landlords collect rents and also the rising prices for their land in their sleep.

So every economy, as viewed by the classical economists, was divided into two parts. There was a production part of the economy, and then there was a rentier part of the economy, the property relations and credit relations and rent relations that were superimposed on the productive economy as an economic overhead. And the idea of the industrial economy was to bring prices in line with the actual cost value as little as possible. And that was what was going to make economies more successful and make industrial capitalism so much more powerful.

Well, if the Corn Laws continued to block lower priced imports, that was going to keep food prices up and hence the subsistence wage, and that would discourage new investment. [And landlords waged] a huge campaign. They lost. And Ricardo said that would bring capital accumulation to an end. And he wrote, “capital can then not yield any profit whatsoever, and no additional labor can be demanded. And consequently, population will have reached its highest point. Long indeed before this period this very low rate of profits will have arrested all accumulation, and almost the whole produce of the country, after paying the laborers, will be the property of the owners of land and the receivers of tithes and taxes.”

And the taxes were mainly to pay financial charges. [The chart bellow] will show how the economy will grow, but as rent takes more and more, the profit will fall to a point where it’s utterly extinguished. And without profits, there’s no incentive for industrialists to invest. And Ricardo wrote all this in his chapter on profits, in his book on The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.

And in the Destiny of Civilization, I discuss in more detail the reform program of industrial capitalism. And the point of writing my book on civilization is there are two kinds of economies. We’re no longer in an industrial capitalist economy. And most people call our economy capitalist, but it’s not the industrial capitalism that was discussed in the 19th century or what Marx meant in Capital or what Werner Sombart meant when he coined the word capitalism in the 1920s. It’s finance capitalism. And the financial sector now backs the monopoly interests and the rentier interests and the real estate interests.

And you’ve had land no longer belonging to a hereditary monopoly. Anybody can buy a house or a commercial building, but they have to go into debt to do it. And the land rent is all paid to the banker, not to a landlord class anymore. And over the course of, say, the 30-year mortgage that was standardized after World War II and created the American middle class, the banker actually got more money in the form of interest than the seller of a house or a commercial property building got.

So you have the price of housing, or whether you rent it or whether you buy it, that employees have to pay in the United States and Europe has to be high enough to cover the costs of paying interest and fees to the banks. And you have, if you look at both the European economy and the American economy, what they call gross national product seems to be growing, but almost all this growth in gross national product is rentier income. Interest is charged as providing a service. And late fees for banks, for credit cards that are higher than the interest rates charged, are providing a service and monopoly prices are all included in GDP. And so there’s very less of product in gross domestic product and more and more of economic overhead.

Well, how did this come about? By the late 19th century, the landlords and especially the financial classes fought back against classical economics. And classical economics was the ideology of industrial capitalism. Free economies from rent. A free market was a market free from rent. And the reaction in the United States, it was led by John Bates Clark. In Europe, it was led by the Austrian school of anti-government, anti-socialist economists. In Britain, it was led by the utilitarian theorists that said, well, there’s no difference between price and value. A price is whatever utility consumers are going to pay. They used a circular reasoning for all this.

So I think I had my next book that I’m working on now has to take a step back and say, how do you think about an economy and how it works? And that is the key to understand why this fight between the West, America and Europe, looks at China and Asia and other countries that are following this original plan of free market classical economists as civilizational, because they look at the rentier interests, the interests of bankers and bondholders, the interests of landlords, and the interests of monopolists. For them, this is civilization. And for the whole takeoff of individualism and free markets in the 19th century, Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, and what became the whole socialist movement and social democratic movement that was backed by the American industrialists and the conservative parties in England, they said, well, we all want to make our economies more productive and we have to get rid of classes that collect income without adding to production, without working, that make money in their sleep.

So there’s this fundamental distinction between earned and unearned income, a productive sector and an overhead sector. And none of that occurs, is taught in today’s economics curriculum. The fight by the finance and real estate sector, mainly together, says there’s no such thing as economic rent. There’s no unearned income. And they’ve used the rental income that they have and all of the debt-financed capital gains from real estate and from their investment in corporations to buy control of the political process and to privatize it. And since the 1980s, especially, from Margaret Thatcher in England to Ronald Reagan in the United States to the social democratic parties of Europe, you’ve had a movement towards privatizing public infrastructure, saying, well, private managers can do a much better job. So let’s privatize the water system. Let’s sell Britain’s water to Thames Water Company. Private enterprise can certainly be much more efficient and less bureaucratic. Let’s have British railroads, in turn, privatized. That’s certainly going to be more efficient.

Well, you’ve now seen water prices go way up for British consumers and industry. You’ve seen railroad prices go way out, and they’re not serving suburbs like they were before. The bus company that was public was privatized, and to make more money, it just cut back the routes to places that had low ridership further out from London. You have the whole thing free in Europe.

Well, what do we have today that’s the equivalent of the high price of corn and meaning grain, for England? The equivalent today would be energy because every industry needs energy, houses need electricity for heating, and they need gas for cooking if there is a gas line around. And the labor theory of value did not take into account capital productivity. The Americans did. Starting in the 1850s. The Americans, and I wrote my dissertation on the economist Erasmus Peshine Smith, who developed this theory as the basis for the Republican Party platform when it was created in 1853. They said, well, the shift, the progress of civilization has been from natural wind energy and water power to first to coal and then to oil and gas.

And at that time, nobody had seen other forms of electricity, atomic power, for instance. And nobody had anticipated that what had been windmills in Holland and other places would be these gigantic wind power constructions that China has made in the Gobi Desert and throughout China. And today you have China realizing that, well, we’re not going to leave this to private enterprise to develop because it takes a long time to develop electric power as an alternative to oil and gas. It takes a long time to make an electric utility in the United States. When you go through all of the filing and meeting all the requirements and the bureaucracy, it takes 10 years for a new electrical company utility to be built in the United States.

Well, there’s another problem that the, one of the major rent-seeking classes that’s taken over politics in the United States, in addition to banking and real estate, is the oil industry. And the coal industry, in particular states, is very powerful too. And they’ve bought control of the Trump administration. And Trump has said, I represent the coal industry. We’re really, the oil industry. We’re really going to take off with oil, with natural gas, and we’re going to use that as power. We’re going to, number one, we’re going to block Europe from depending on energy and oil that is not produced by the United States and its allies. We’re going to say, you cannot import oil from Russia anymore or from Iran or from Venezuela. You have to buy oil and LNG, natural gas, from us. And that’s happened. And one of the results of America selling the liquified natural gas to Europe is that gas prices in the United States are rising.

Well, all of this has become what the government describes as civilizational because of the intention of the American economy to say, we have a problem. We no longer can compete with other countries in an industrial capitalist way like we could in 1945. We’re no longer an industrial company. We’ve offshored our labor and industry to other countries, mainly to Asia. And the only way that we can, have other countries subsidize us is to say there’s a Cold War with Russia and China. And we have to defend Europe from the imminent invasion in a year or two that Russia is going to be willing to lose another 22 million people trying to invade Europe and recapture East Germany for itself. Well, this is all nonsense, but on the umbrella of this fiction, this fictional narrative of a Cold War, the United States convinced the NATO members: yes, you have to avoid free trade.

Well, this is the fight that British industrialists won in 1815 and German industrialists lost today after 2022 by cutting off the trade, the energy trade with Russia and other countries, and following it up by cutting off technology trade with Russia, such as Holland did when it said it closed Nexperia down and said we’re taking it over because we cannot permit any Chinese-owned firm in the West. And just a few days ago, Donald Trump, America, put pressure on Panama’s Supreme Court to confiscate China’s investment in the port development in the Panama Canal to try to prevent that. So you’re having what does indeed threaten to be a civilizational war. And it’s the war about, is there going to be a government that represents the development of the people at large in economic growth and prosperity, or will it be the government of the enemies of prosperity, the rentier class.

If you let the financial sector and the real estate sector and the monopolies take control of all of the public utilities, of the land and untax it and create credit to essentially create financial wealth by creditor claims that represent the debts of the 99%, or at least the 90%, well, then you’re going to have the economy coming to a halt. And if the United States is really serious about the Cold War, if it says to Europe, we’ve already convinced you to fight to the last Ukrainian for land, we can’t give Russia an inch of land. So Mr. Zelensky tells us we’d rather have the Ukrainian people die. People don’t matter. Control of land matters. Hurting Russia matters. And the fact that you Germans lost to Russia twice, World War I, World War II, maybe you can get even this time. Let’s fight the war all over again by military Keynesianism. If you make the military arms, you’re going to actually use them in Russia.

Well, this fight between rentier finance capitalism centered in the United States based on infrastructure, on artificial intelligence monopoly, on computer monopoly, and information technology is supposed to be able to replace America’s industrial profits that it had made in agricultural exports, which were the key to America’s balance of payments and dominance of the system after 1945. They want to replace this with monopoly rents for information technology and artificial intelligence. Well, Europe had threatened to say, well, one of the problems is not only are you charging monopoly rents, but you’re insisting that we Europeans don’t even tax them. We’re supposed to tax our labor. Shift it onto labor, shift it off business and the rentier income, and especially shift it off the Americans.

And so Trump said, well, we’ll stop that. We’re going to slap tariffs on you and disrupt your economy. [And your companies] will not be able to have access to the U.S. market. And also, through NATO, fortunately, we’ve used NATO to control the European Union, as you and I have discussed before, and they’re surrender monkeys. And they surrendered and said, okay, we’re not going to tax the United States monopoly. We are going to be dependent not only for gas, on the natural, on the United States, but on information technology. We’re going to let all of our growth in wages and growth in income be paid to the United States, after all, because we depend on you to protect us from the threat of Russians marching right into Germany on their way to Britain.

This is crazy. And I guess you could say that civilizations fall because they don’t understand the economic dynamics that have made them successful in their takeoff from the very beginning. My whole, my book on the collapse of antiquity showed that the first form of rentier income that ended up destroying antiquity after centuries of civil war from the 7th century BC right down to the time of Caesar and the end of the Roman Republic was the demands of the population for a cancellation of debts and a redistribution of land. That fight failed, and the result was feudalism.

So we’ve had the Roman Empire, which was, I guess you could call it Western civilization at that time, lose its quality that had made it civilization and become decadence. You’re having the same thing happen today in similar terms. Asia, for thousands of years, had a completely different basis for social philosophy and government, all the way from Confucianism that said that if you have an emperor, the emperor’s role is to keep the population happy and not revolting. If there’s a revolt, then the emperor loses his justification for being an emperor. Same thing in the takeoff of Western civilization, which was really in the Middle East, in Mesopotamia, in Egypt, in Sumer, Babylonia, and Egypt.

And all the early Bronze Age civilizations from the third millennium BC down to the first millennium BC regularly canceled the debts to prevent an oligarchy from taking over. Every king of Hammurabi’s dynasty began his rule by canceling the debts, returning land to cultivators that had lost it so they could regain it and begin to pay taxes again and serve in the army and serve as corvée labor building the infrastructure projects that Mesopotamia had. Same thing in Egypt. When archaeologists and Egyptologists finally began to be able to translate what the Egyptians wrote, it was the Rosetta Stone that was a debt cancellation, canceling tax debts. When the young pharaoh was told, well, do what the earlier pharaohs did, cancel the debts and free the population so that it can work. Otherwise, you’re going to have a concentration of land ownership and it’ll be impoverished.

The same thing happened in the Jewish lands in Judea. After the Babylonian captivity and the Jews returned, they brought the laws of Leviticus, the Mosaic law 25, saying word for word, what Hammurabi’s debt cancellation did: free the debt bondservants, cancel the debts, and redistribute the land that had been forfeited. That was put at the center of their religion because by that time, in the first millennium, kings were no longer good, certainly in the West, and Israel had become part of the West pretty much at that time.

And so you could say that change in civilization occurred really beginning 2,000 years ago, 2,500 years ago, between the West that did not cancel the debts and restore order by circular time. The Asian countries from the Middle East to China all recognized that economies tend to polarize as the wealthy people take over government, become the vested interests, and essentially try to dismantle public authority and prevent rulers from protecting the population and its means of living and its land tenure from being concentrated in the hands of an oligarchic class.

The West emerged as an oligarchy from the beginning. In that sense, we’re in a civilizational conflict today because, again, it’s between the rentier class, originally the creditor class, becoming the landowning class for land rent, and gradually monopolies that were created in the feudal Europe in order to enable kings to find an income source to pay the international bankers for the war loans they were taking out to fight each other and take over land.

So you have a complete, you do have a civilizational dynamic, and the civilizational dynamic began to merge and become more reasonable in the Industrial Revolution. It was industrial capitalism that was radical. It said, we want the same thing that was fought over in Rome, in Babylonia, and in the Jewish lands when Jesus opposed the vested interests and gave his first sermon, unrolling the scroll of Isaiah and saying, I’ve come to announce the cancellation of debts. That was what the original of Jewish Christianity, you could say Jewish Christianity.

So this is what’s tearing things apart today. Well, I mentioned in the United States, there’s a problem with how can America get the monopoly in artificial intelligence and computer manufacturing and other high-tech Silicon Valley technology if it doesn’t have electricity. And Trump has prevented America from getting electricity in the form of windmills or solar energy. And he says coal is one of the fuels of the future. And the Trump administration has canceled the planned close down of coal utilities because the Biden administration at least had scheduled these for closed down because of global warming.

And so Trump not only has closed alternatives to carbon energy, but he’s also withdrawn from the Paris Agreements and is opposing the whole movement by the rest of the world to try to free energy production, which is the key to productivity, from dependence on carbon. That has become a civilizational threat because global warming is in the natural environment is one of the things that destroyed the Babylonian civilizations after 1200 BC when there was global freezing that caused droughts and huge population movements. Climate change had also destroyed the Indus civilization in 1800 BC. So there are certain external factors, in addition to internal dynamics, that threaten to destroy a civilization.

It’s happened before, and you can trace it throughout history. And it’s threatening to transform and even destroy the way in which Western civilization and the world that’s been brought into submission to Western civilization’s values, live for the present. The financial return lives for the present. The present is the future. All that matters is year to year. The oil companies don’t care if the burning oil is going to add and accelerate global warming and make it worse because they’re in the business of making profits, I should say, economic rents, from their oil.

Well, without Western civilization going back to the analytic value, price, and rent theory of the classical economists, it’s not going to realize the fact that, oh, we’re not really being productive anymore. And we’ve deindustrialized. And by letting Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan be the tools that have represented this anti-government, anti-socialist philosophy saying it’s a free market not to distinguish between productive and unproductive labor. No such thing. It’s a free market to let the rich property owners do whatever they want and take control of government and finance the election campaigns and essentially wage war against any countries that do not follow the same anti-government, pro-rentier, pro-oligarchy form of government that Western civilization has become.

Well, I think that the problem you could, the great threat to Western civilization is neoliberalism, which denies this existence of economic rent and it treats rentier income as an actual product and thinks that, well, GDP is going up. If the bankers are getting rich, all of this debt service payment of interest is going up, that’s a product. All of the rents that people are paying for the rising cost of real estate, that’s a product. And somehow monopoly prices are all, well, it’s all if people are willing to pay it, it’s consumer choice to pay the monopolies. There’s no such thing as economic coercion. The whole rhetoric of economic thought has been changed into a kind of vocabulary of deception instead of a vocabulary explaining the actual dynamics of how economic systems and, ultimately, how civilizations work. I think that was a long answer to your question.

GLENN DIESEN: Well, no, it’s an excellent answer. And well, I find it fascinating because, you know, as I said, with the classical economists, the industrial capitalists, they focused so much on exactly this issue of, well, reducing the role of the rentier class or at least reducing the rent-seekers altogether. And again, this is a key focus. And but yet, now that we’ve seen this shift into this finance capitalism, where we now look at the rentier class as just a great, excellent capitalists, it’s fascinating because we invoke, we refer to John Stuart Mill and all to justify why there should be no redistribution as if the concept of a classical economy or industrial capitalism is some kind of a socialist conspiracy. But so it is strange to see how the neoliberal capitalist idea, how it formed an ideology which allows it to borrow from the same thinkers (inaudible) to some extent.

I just had a last question about well when you refer to the Europeans. Obviously, the United States can’t compete with China. It seeks now rent from around the world, which is a beneficial position the United States has been in. But with the Europeans, it appears to become more aggressive, as you said. They say, you know, you have to buy weapons, you have to buy energy. And as you learn, there’s a very heavy markup there or an ability to extract a lot of rent. And also, if the Europeans want security, they should also make sure that their profits are reinvested back into the United States. And of course, the Europeans are doing so, but this is also resulting in economic devastation for the continent, which will then, I guess, at some point play out both in political and security problems.

But China and Russia, though, they seem to be, as they decouple from the American-led system, is this I guess a source of economic growth for them? Because one of the ideas was we’re going to put sanctions on the Russians, we’re going to crush their economy. If you remember at the beginning of the war, you know, the ruble was going to become rubble and we would have their economy smashed before the end of the weekend. And it didn’t work this way.

Instead, we saw that as the Russians cut themselves off from Western technology, banks, currency, that instead they had significant growth, of course, based more in the industrial sphere as opposed to this traditional or not traditional, but this new finance capitalism. But do you see part of the successes for both China and Russia being that they cut themselves off from this, I guess, uncompetitive, rent-seeking American technologies, banks, and currency?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, it’s not that they cut themselves off. Donald Trump cut, and America cut them off, much to their benefit. You mentioned that socialism was a conspiracy. That’s not it. Socialism was viewed as the next stage of industrial capitalism. In the late 19th century, not only Marx was talking about socialism, there were all sorts of kinds of socialism. There was Christian socialism, there was anarchist socialism, there was social democracy. And what everybody was in agreement, all of the vested interests, was you needed governments to play an added role in the economy to provide basic needs at subsidized prices. And it was the America’s first economics professor at the first business school, the Wharton School, that said, Simon Patten said that public infrastructure is a fourth factor of production besides labor, capital, and land, which really isn’t a factor of production, but rent extraction.

But public infrastructure doesn’t aim at making a profit. It aims at minimizing the price of basic needs so that labor doesn’t have to cover these costs and employers won’t have to pay for these costs because public investment is more productive and less high-priced than private investment because the aim of public infrastructure, canals, railroads, public health, is not to make a profit, it’s to make the economy profitable. Well, it was the Conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli in Britain that said health, public health, that’s the center of things. And it was Disraeli that promoted public health, as opposed to the United States under President Obama that says we’ve got to privatize public health. And the American Medical Associations, ever since the 1950s, fighting, we’re against socialized medicine. Well, it ends up that instead of socialized medicine taking over the medical practice of doctors, the private health insurance companies have taken over what doctors can do here and pressed the cost of medical care to 20% of GDP.

Well, this is far in excess of what other countries from Europe to China do. China offers public health and also free public education, as England did for a long time, and as many European countries did. But now it’s very expensive, everywhere from over $50,000 a year at least in the United States to high prices for English, Australian, and other Western English-speaking universities, and I guess in German universities. All of these functions that were supposed to create a competitive, low-priced economy are now being privatized, high-priced, and countries such as China and Russia are keeping the price of basic needs low, and they’re doing what is supposedly what democracies are supposed to do. The Americans say, we’re democracy against autocracy, but that’s not what this fight is all about. It’s against Western oligarchy versus socialism, state industrial capitalism with a strong public subsidy. And this subsidy prevents a financial oligarchy from developing because what China has done in going further than the socialist movements have advocated in the West is to say, money is a public utility and we’re creating money and credit through the People’s Bank of China to not to finance corporate takeovers and making money financially by financial engineering. We’re using money and credit to finance actual construction.

Well, they’ve over-financed housing construction, obviously, but they’ve also financed their industry, they financed their wind farms, they’re financing their basic research, or at least providing government subsidy and support for private enterprise doing all of these. There’s a mixed economy. Every successful civilization in history has been a mixed economy. And when you have the vested interests saying we don’t want a mixed economy. We don’t want government regulating or taxing us. We want to control the economy ourselves. We want the money that the government would tax to come to ourselves as our own income. We want to impoverish the rest of society and make it dependent on ourselves. Maybe it’ll create a revolution, then we’ve just got to fight them. And we’ve got to fight other countries that want to get rich by a strong public sector.

So it’s China above all that’s doing what Western democracies claim to be doing, but they’re not doing because they’re not democracies. They’re oligarchies. And the vocabulary that is used for the Western narrative is, well, China is an autocracy. And if any, they say, if you regulate a company and regulate monopolies, that’s autocracy. If you tax the rich instead of taxing the wage earners as much, that’s autocracy. If you’re preventing us from charging monopoly prices or exploiting people or raising interest rates to usury levels, well, that’s autocracy. Anything blocking what we want to do to make money by indebting the population and by turning it from a home-owning, self-sufficient class into a rentier, renting, dependent class, that’s autocracy. Well, they’re making autocracy sound like something that is really, really good. And of course, it used to be called socialism.

So, again, you’re having the economic vocabulary of deception become the basis of this narrative. And I wrote my book, J is for Junk Economics, on exactly this transformation of vocabulary. And if you have an adequate vocabulary, that’s going to help you understand the actual dynamics of how the economy, any economy, works.

GLENN DIESEN: Well, thank you for the extensive answers. I really think people should appreciate more the concept of rent-seeking in order to appreciate the stage we have in the current economy and also what this means for civilization. So, as always, thank you so much for sharing your wisdom on this. And for anyone who wants to buy the book, I will leave a link in the subscription. And again, you’re quite a prolific author so there’s plenty to get there. And also, of course, I’ll leave a link to your website as there’s excellent material there all the time. So thank you very much.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, thanks. I also describe this whole account of economic rent in Killing the Host, which is an early version of my history of rent theory and what’s happened there. And my Superimperialism has just been created, by the way, as an audio book, and that’s just being made available now. So people are picking up this idea. But the fact that, you know, if you look at what are the Nobel Prizes given for. They’re given for denying the theory and the concept of economic rent. They’re essentially, it’s for junk economics that denies all of this. We’re really, that is the civilizational fight over how do you understand an economy and think of its dynamics. That’s really what this is all about. So you’ve asked the right question. You always ask the right questions, Glenn. That’s why I like being on your show so much.

GLENN DIESEN: Thank you. I appreciate that very much.