Outlaw US Empire’s Hegemonic Spasms

A Chinese View.

with appreciation to Dr. Karl at karlof1’s Geopolitical Gymnasium.

“the more the United States openly abuses its remnants of military might, the weaker its actual power becomes .. the new order is struggling to draw strength and try to break through the ground .. China and Russia are more likely to choose to wait for the dust to settle and use this [Venezuelan] incident to alert the “Global South” .. a kind of strategic patience in the gap: low-cost, high-leverage, turning the overreach of the United States into a self-devouring fire.”

Events are happening on close to a daily basis as the Outlaw US Empire tries to mask its decline by using what remains of its ability to project power. Many know of the recent illegal seizure of a Russian flagged vessel in international waters by the Trump Gang. Russia’s MFA issued a statement that I translated and posted here that’s very legalistic serving as a message to the Global Majority on the grounds Russia stands on when the next attempted seizure occurs. One other important note; I discovered that the Novgorod area the Outlaw US Empire attacked using Ukraine as a mask wasn’t just the location of a nuclear command bunker and adjacent presidential residence, but is also the area where Putin’s family resides (yes, he does have extended kin), which is an old Mafia tactic to attack one’s family to obtain compliance. Since that attack, the Kremlin has been silent except for Putin’s New Year’s and Christmas messages to Russians. The same can be said for almost all other areas of the Russian government. The negotiation kabuki theatre has ended, and we’re back to the Biden Era stand-off.

All that aside, I came across what IMO is a good evaluation of the situation from a Chinese academic writing under his pen name Bao Shaoshan that was posted at Guancha. Here’s my translation of its title: “When a Hegemon Declines, It Turns to Its Waning Military Strength, Thus Proving Its Decline:”

Late at night on January 3, 2026, the United States launched an airstrike on Venezuela and forcibly took President Nicolas Maduro and his spouse from his residence with special forces. The Trump administration described the operation as a “law enforcement operation” against so-called drug trafficking, but it was undoubtedly a military attack that was a flagrant violation of international law. The operation was not only accompanied by bombing, but also the blatant abduction of the Venezuelan president and his spouse to the U.S. amphibious assault ship USS Iwo Jima on the high seas.

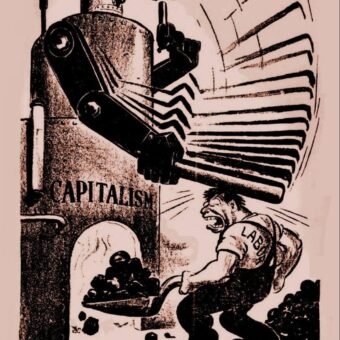

This act is not only a blatant violation of international law, but also a clear reflection of the reality of the continued decline of the United States. The international reaction further highlighted the waning of U.S. hegemony when Venezuelan Vice President Delci Rodríguez denounced the move as a kidnapping aimed at plundering the country’s oil resources. Instead of demonstrating unshakable strength, the operation revealed how a superpower turned to naked aggression and coercion at a time of decline in influence.

The abduction of a sovereign leader of a country in the absence of any international authorization or due process is contrary to the fundamental principles of the post-World War II international order. Article 2, paragraph 4, of the UN Charter expressly prohibits the use of force or the threat of force to violate the territorial integrity and political independence of States, and the airstrikes and the kidnapping of the Venezuelan president to New York for trial are a violation of that principle.

UN Special Rapporteur Ben Saul characterized it as “illegal aggression” and echoed widespread condemnation in Latin America and beyond. Within the United States, voices, including Rep. Delia Ramirez, have accused it of being a “war crime” and linking it to a series of U.S. histories of intervention in the region. These interventions have left a legacy of poverty, displacement, and long-term instability.

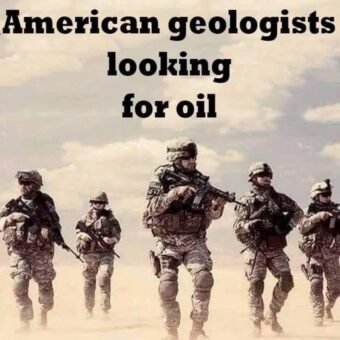

Trump’s claim that the United States will “regulate” Venezuela until a “suitable transition” occurs unabashedly reveals its true intentions: U.S. operations in Venezuela are not anti-narcotics, but resource control grabs similar to those in Iraq or Syria. In a world where hegemony is no longer stable, such behavior does not send a signal that the strength of the United States is still the same, but reveals traces of hegemonic despair.

Emanuel Wallerstein pointed out in his book The Decline of American Power (2003) that American hegemony peaked between 1945 and 1970, and then gradually declined driven by structural factors such as the rise of economic competitors, the trauma of the Vietnam War, the process of decolonization, and the ideological shock of 1968.

By the beginning of the 21st century, military superiority was still the main pillar of its influence, but its excessive use of this tool exacerbated the vulnerability of its hegemony. As a summary of its argument: the more the United States openly abuses its remnants of military might, the weaker its actual power becomes.

The case of Venezuela vividly illustrates this mechanism. The unilateral nature of the operation highlights the boundaries of its power: it alienates partners and stimulates a backlash from opponents. Putin’s warning about a potential global escalation is a reflection of this backlash. From Mexico to Brazil, Latin American countries are mobilizing diplomatically and economically to resist this neocolonial practice.

In his 2006 book The American Power Curve, Wallerstein pointed out how unilateralism after 9/11 transformed an otherwise slow decline into a more violent and rapid decline: foreign intervention aimed at reaffirming hegemony not only fails to consolidate dominance, but instead consumes resources, erodes the foundation of alliances, and gives rise to broader resistance.

This is mutually confirmed by the recurring history: the Bay of Pigs, the invasion of Grenada, the invasion of Panama, and the Iraq War, almost all of which ended in backlash and continued to accumulate resentment in local society. In Venezuela, where prolonged sanctions and external interventions have weakened economic fundamentals and driven population exodus, the Maduro regime has been able to maintain its resilience through ties with countries such as Russia, China and Iran.

Today, the kidnapping could trigger an escalation at the proxy level and even a broader regional conflict; The Venezuelan leadership has publicly vowed to resist. According to Wallerstein’s judgment, countries in the late stages of hegemony often turn to “military strength” when their economic and cultural dominance declines.

This approach usually frustrates the hegemonic state, which in turn accelerates the process of multipolarization. In this context, when more hidden, sophisticated and institutionalized control methods fail, violent coercion is grasped by the declining hegemon and becomes a last resort and a tool of last resort.

If we want to understand the essence of the decline of the United States reflected behind the US invasion of Venezuela, we must go back to the deeper roots of economic imperialism. This is the path that Washington has relied on for more than a century. Venezuela has the world’s largest oil reserves, a structural resource advantage that has long made it a key target for external powers, especially the United States.

As early as the 19th century, Washington intervened in Venezuela’s affairs; The discovery of oil in the early 20th century further strengthened this involvement. During the reign of dictator Juan Vicente Gómez, the ruler, known for his corruption, amassed a fortune equivalent to billions of dollars today via lucrative concessions for U.S. oil companies such as Standard Oil, as well as Royal Dutch Shell.

Romulo Betancourt, an important figure in Venezuela’s mid-20th-century democratic politics, once described Gomez as “a tool for foreign powers to control the Venezuelan economy, an ally and servant of powerful external interests.”

This exploitative structure did not end in subsequent regime changes. The United States has supported the repressive dictatorship of Marcos Perez Jimenez: its security forces have tortured, killing thousands of people, but at the same time offering extremely favorable conditions to multinational corporations. Washington awarded Jimenez the “Legion of Merit” and assisted its NSA in suppressing dissent.

Even after the fall of Jimenez in 1958, when a nominal democracy was established, American influence continued and solidified its influence through economic leverage and support for anti-leftist forces. Its policy logic is clear: the U.S. strategy toward Venezuela prioritizes access to oil resources and related interest arrangements over Venezuela’s sovereignty claims or human rights situation.

By the end of the 20th century, this economic domination continued to accumulate and induce systemic crises, paving the way for the rise of the Bolivarian Revolution. In the 80s and 90s of the 20th century, Venezuela promoted neoliberal policies under pressure from U.S.-backed institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, which often focused on austerity measures and severely damaged the living standards of the general public.

Under these policies, Venezuela’s domestic poverty rate soared from less than 20% in 1979 to more than 50% in 1999, causing large-scale unrest, such as the 1989 Caracasso riots, in which security forces killed hundreds of people in protests against rising prices.

Spreading corruption, rising inequality, and growing alienation from the political system controlled by the elite all combine to create fertile ground for change. Hugo Chavez drew on Simón Bolívar’s ideals of independence, anti-imperialism and social justice, winning the 1998 elections and promising to redirect oil wealth to the people.

The “Bolivarian Revolution” promoted the nationalization of key industries, funded social programs such as education, health care and poverty alleviation, and significantly reduced inequality, with the Gini coefficient falling from nearly 0.5 to 0.39 between 1999 and 2011.

The U.S. response was swift and punitive. Washington immediately saw Chavez’s resource nationalism as a dual threat to corporate interests and ideological hegemony and escalated its intervention. The United States provided tacit support for a coup in 2002 that briefly overthrew Chavez. Sanctions against Venezuela were officially launched in 2006 in the form of an arms embargo on the grounds that Venezuela “does not cooperate” in counter-terrorism and counter-narcotics.

During the Trump presidency, sanctions were further extended to financial restrictions (2017 E.O. 13808 prohibits U.S. involvement in Venezuelan debt and Venezuelan National Oil Company PdVSA-related transactions), oil sector bans, and sub-sanctions against third parties. The Biden administration proposed a temporary relief mechanism linked to election concessions, but it has regained weight in the 2024 election dispute. These measures hit Venezuela’s economy hard, exacerbating shortages and migration, but failed to achieve the goal of overthrowing the government until military intervention in 2026. This intervention became the “logical end” after decades of accumulating economic wars and regime change demands.

This narrative in Venezuela is also embedded in the broader history of regime change in Latin America. Stephen Kinzer examines this in his 2006 book, Overthrow: America’s Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq. Kinzer pointed out that for more than a century, the United States has instigated and overthrew 14 governments around the world, often driven by economic interests, supplemented by ideological and security narratives as justifications.

In Latin America, this pattern dates back to the imperial era: the United States intervened in Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Nicaragua and Honduras, and the U.S. military or its agents took over key matters to secure access to resources and markets. [Many interventions aren’t mentioned nor is the “imperial era” over.]

During the Cold War, “anti-communism” further amplified and institutionalized these actions: the 1954 CIA-orchestrated Guatemalan coup that overthrew President Jacobo Arbenz was directly triggered by land reforms that touched the interests of the United Fruit Company, culminating in a civil war that lasted decades and killed tens of thousands of people.

In Chile, the United States supported the 1973 coup d’état that overthrew Salvador Allende and supported Augusto Pinochet to establish a dictatorship, resulting in the killing of more than 3,000 people and the torture of tens of thousands. Kinzer defined Grenada (1983) and Panama (1989) as typical examples of the “era of invasion”: direct military operations in the name of democracy or anti-narcotics, overthrowing incumbent leaders, but whose real intentions were often to obscure deeper objectives such as resource grabbing or strategic control.

Kinzer’s analysis further reveals the recurring motivational structures in these actions: protecting the interests of multinational corporations, curbing nationalist demands, and suppressing perceived threats from the left. However, such interventions rarely deliver on their public commitments. Original triumphalist narratives such as George W. George W. Bush under the banner “Mission Accomplished” in Iraq. It was soon replaced by a more chaotic reality: chronic instability, human rights violations, and a backlash of anti-American sentiment.

In Guatemala, the coup induced guerrilla warfare and eventually turned into genocide against indigenous peoples; The Pinochet era in Chile solidified inequality and oppressive rule, which in turn fueled regional resentment; The failure of the Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba (1961) not only lost face to the United States, but also consolidated the Castro regime and inspired revolutionaries throughout Latin America. In Nicaragua, U.S.-backed “rebels” waged a decade-long war against the Sandinists, causing widespread atrocities without lasting regime change.

Even seemingly “successful” cases like Panama’s “Just Cause” overthrow of Manuel Noriega where the operation also brought short-term confusion and long-term deep doubts about U.S. intentions. According to Kinzer, these interventions often sow seeds of instability, erode U.S. credibility, and breed the threats it claims to eliminate.

Antonio Gramsci’s insight in “Notes from Prison” in the 30s of the 20th century is particularly enlightening here: “The crisis lies precisely in the fact that the old is dying, and the new cannot be born; During this ‘gap period’, there will be all kinds of pathological symptoms.”

Ninety-five years later, we seem to be walking in a similar gap. The unipolar era is collapsing under the multiple squeezes of continuous conflicts, economic shocks and the rise of emerging forces. The future contours of the multipolar or “multi-node” era are still uncertain. The future direction of the world is still an open question, and its direction depends on the evolution of events, not some inevitable fate.

Gramsci’s so-called “pathological symptoms” are particularly concentrated in the eerie repertoire of a hegemonic country kidnapping the leader of another country in the name of law: it puts on the cloak of so-called legitimacy while avoiding its own responsibility in global scourges such as drug proliferation or rights violations. This transitional phase is also more prone to confusion. The emergence of roles in the Trump cabinet, such as Marco Rubio, who advocate regime change, is a concrete manifestation of this decay.

Rubio portrayed raids as routine law enforcement, almost unbelievable; That’s nothing more than a modern warfare version of old gunboat diplomacy. Meanwhile, the Global South is exploring alternative options such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative or BRICS, which promise aid without an invasion, but these arrangements also create feedback loops in their own ways, triggering and amplifying Washington’s anger.

The United Nations, originally conceived as a bulwark against aggression, is now more like a decorative relic of 1945 optimism: it has become an arena for speeches with collective security as its institutional goal. The Security Council is subject to the veto mechanism, and its resolutions have been repeatedly ignored by the powerful.

The rapporteur’s weak condemnation of the Venezuelan events underscores this institutional incompetence: neither the ability to urgently convene a meeting nor the substantive punishment of the provocateurs. In the face of systemic destruction, there are only words left. The ICC presents a similar dilemma: it hunts down the weak while ignoring the centers of power. Wallerstein foresaw the delegitimization process of such institutions in the process of hegemonic decline, which would eventually become a relic of the previous era.

The uncertainty of this gap period will also further amplify systemic risks. Multipolarity can produce collaborative equilibrium, such as de-dollarization, regional integration, innovation-driven partnerships; It may also dissolve the world into opposing camps.

China’s rise, Russia’s resilience, and India’s growth all suggest that there is no longer a single arbiter in a decentralized order. However, the actions of the United States in Venezuela have objectively promoted division and camping. Europe’s mild-mannered reaction to the Venezuelan attack encapsulates this sense of fluidity and disorder. The United Nations and all its subsidiary devices are more like a façade. With the end of “peace under American rule” and the gap period unfolding, the “age of monsters” has indeed arrived.

Liberalism is de facto over; it has been abandoned by the United States, reduced to an organizational idea, or reduced to a smoke bomb. It remains to be seen what kind of “post-liberal” system and structure will emerge. What is certain is that the current liquidity has increased significantly compared with the previous period. Moreover, there is far more than one possible form of “postliberalism”.

As for the United Nations itself, although China and Russia have always been firm in their support, at least formally, for the United Nations and its subsidiary organizations, it is becoming increasingly difficult for Russia to believe that this framework will be maintained for a long time as the situation progresses. Only the naïve will believe that real governance can happen within the United Nations at this moment. The cloak of liberalism has been torn apart by the United States. And above the multipolar horizon, it is full of uncertainty, and perhaps even grotesque, terrifying trajectories.

Expanding the horizon to a broader historical picture will make the above judgment more profound. After 1945, the American empire thrived on reconstruction aid and cultural exports. But the oil embargo and inflation in the 70s of the 20th century have exposed its structural cracks. Reagan used policies and narratives to cover up industrial hollowing out in the 80s of the 20th century. The unipolar self-confidence of the 90s gave birth to excessive complacency, which eventually gave birth to endless overseas intervention after 9/11.

The Afghanistan collapse in 2021 and the continued defeat of Ukraine reflect the backlash mechanism revealed by Wallerstein that is working. Venezuela adds another to the list: a resource-rich target is once again locked in as U.S. energy anxiety rises.

The specter of Gramsci also hovers in the United States: deepening domestic political divisions, income disparities, and a political logic of diverting attention from domestic decline through external adventures. Trump’s “return” combines isolationism and aggressiveness to reflect the paradox of the gap period: the new order is struggling to draw strength and try to break through the ground, while vested interests such as the energy cartel, the combination of the military industry and nostalgic imperialism continue to stall its evolution.

This uncertainty means that there is no predetermined trajectory ahead, but the general trend seems to be more inclined towards escalation rather than relief. In the next decade, the spillover and amplification of violence may be even more pronounced: not only in conventional warfare, but also in “invisible wars” – cyber infiltration, economic siege and influence infiltration operations.

Aggression in the “gray zone” that can circumvent open conflict may become the norm. At the same time, unstable dirty wars and terrorist acts may increase in various places. This is not a probability or advocacy, but a probabilistic judgment made during a transitional period without a leader: the power vacuum often induces opportunism.

However, there are also opportunities in this liquidity. The openness of multipolarity provides space for diverse political and development expressions: Africa’s claim to resource sovereignty, Asia’s technological leap, and Latin America’s progressive alliances. Venezuela’s resistance may coalesce broader anti-hegemonic solidarity, and its role can be compared to the catalytic effect played by Vietnam in a sense. The plasticity of this era is summoning a variety of “post-liberal” forms, allowing people to transcend existing and increasingly outdated structures.

Presenting the task as “being a good midwife of multipolarity” aptly captures the challenge of the moment: to support in a prudent way in the throes of labor, so that the new order can grow, rather than forcefully presuppose and shape its results. The reader may naturally infer that stability should take precedence over turmoil, but the focus here is on the fragile openness of the moment rather than the proposal of normative initiatives. Diplomats can certainly push for de-escalation, advance reform of a fairer forum, and facilitate the replacement of force with dialogue. But these are only possibilities after all, not imperative inevitability.

For Donald Trump, 2025 was supposed to herald a triumphant return: a second term would be marked by a “America First” victory narrative, border walls strengthened, trade agreements renegotiated, and global respect regained through a more aggressive posture.

However, the reality is presented as a series of retreats, failures and embarrassments. Economic headwinds persist: inflation remains lingering after promises of rapid relief. Supply chain disruptions reveal structural vulnerabilities in a changing world. As BRICS accelerates its de-dollarization efforts, the dominance of the US dollar is also weakening.

At the domestic level, political stalemate deepens, with congressional infighting blocking infrastructure bills and culture wars distracting from rising inequality and the hollowing out of the middle class. Trump’s signature policies have also suffered setbacks: the tariff war with China has brought the nickname “TACO”; The immigration crackdown has overwhelmed the court system but failed to curb cross-border movements; Foreign alliances were further broken.

Venezuela’s move on the node of U.S. action can be called a symbol of desperate hegemony that punches externally at a time of internal weakness. Narcissistic arrogance aside, the bad year ended in a raid on Venezuela – a high-stakes bet to show toughness and deflect domestic woes.

But as Wallerstein might remind, this high-stakes game itself is a classic symptom of a declining power: when the economic and political situation deteriorates, the declining powers respond to external suspicion with overexpansion, which only exacerbates the downward spiral. Such actions also show that the United States has not adapted to the economic realities of the post-unipolar era, and still clings to outdated tools of coercion, rather than institutional and technological innovation for multipolar markets.

Once upon a time, American companies dominated the global value chain. Today, competitors from other parts of the world are outpacing in areas such as technology and renewable energy. Whether in domestic education and infrastructure investments or embracing multilateral trade, the vulnerability of empires is exposed. In this context, military adventures become expensive distractions to mask the structural decay of their countries.

And historical experience shows that plunging Latin America into turmoil often creates a power vacuum that echoes northward in a vicious feedback loop. Instead of ensuring access to resources or achieving the goal of curbing drugs, U.S. intervention in Venezuela could amplify the crises that Trump has vowed to address.

Historically, there have been regime changes in the region, with Guatemala, Chile, and Nicaragua all having flows of refugees fleeing violence and poverty, which has increased immigration pressure at the U.S. border. Today, Venezuela is a source of millions of migrants. Further disruption could lead to larger cross-border flows, crushing an already strained immigration system and intensifying a domestic political backlash.

At the same time, drug networks that are adept at exploiting volatile environments may be more rampant in the lawlessness that ensues. At a time when regional governance capacity is weakened, they may deliver cheaper and deadlier drugs to the streets of the United States. These are not abstract threats, but more like imperial boomerangs: external intervention will eventually return in the form of internal risks.

Some observers have seen the Venezuelan action as an indirect attack on the broader BRICS ecosystem. Although Caracas is not a key member of the bloc, its alliance with the anti-hegemonic network, its oil, its resistance to sanctions, and its symbolic adherence to anti-American domination in Latin America make it an important node to be reckoned with. Both China and Russia have strongly condemned the intervention: Beijing has accused it of being an “act of hegemony” and Moscow has called it “armed aggression,” but there are very few retaliatory measures that China and Russia can take.

Therefore, China and Russia are more likely to choose to wait for the dust to settle and use this incident to alert the “Global South” to the continuation of Washington’s (and the groveling European Union) colonial reflex, as well as the possible backlash of instability in northern Latin America to the United States. This is a kind of strategic patience in the gap: low-cost, high-leverage, turning the overreach of the United States into a self-devouring fire. The more Washington tries to compensate for its decline with a punch at the outside world, the more it is accelerating the process of multipolarity it fears.

The U.S. invasion of Venezuela is not a dominant expansion, but more like a spasm of a low tide colossus. While unipolarity subsides, the dawn of multipolarity is still full of uncertainty. There are many shadows on it, and possible ghosts lurk. The old order is dying. The shape of the new order depends on how we respond to the uncertainties of the transitional period. And the arrogance of the empire will eventually lead it to decline and become an irrelevant actor. [My Emphasis]

Much discussion at Moon of Alabama echoes the above content, particularly in these two threads chronologically ordered here and here, although there are many distractions within them. The signs of imperial decline of the Collective Western Empire have existed since the end of WW2 until we now have the waning of the Outlaw US Empire. Ridding the world of Imperialism, hegemony and the gross atrocities they generate, some of which were described above, will be a boon for Humanity. However, we must consider what drives those behaviors to which there are several schools of thought, which I won’t go into here. The great irony is the Outlaw US Empire is responsible for its own downfall via its Neoliberal and Neocon policy dogmas, the results of which cannot be undone. It might be possible for an America First policy to succeed, but it’s impossible to Make America Great Again because the foundation of its greatness was offshored and will not return. It’s the latter reality that all too many are denying. And that denial drives Trump’s pleonexia and megalomania that are at the root of his narcissism and the behavior we see.

Yes, there’s little Russia and China can do to enforce the law that’s being continually broken—again, the problem of dealing with a nuclear armed outlaw. IMO, the best the world can do is to arm itself with the types of weapons that will deter the very limited ability of the Outlaw to project power—the very first step is to replace all US related electronic equipment with Chinese or Russian equivalents since all US gear have backdoors that can be controlled by CIA/NSA. Yes, that will take time, but the “gap” period we’re in may last several decades and there’re too many examples of what can be done via that control as was just demonstrated in Venezuela. Even if Trump were to die tomorrow, Vance is just as bad, and the rest of the Gang remains. And remember, the Ds were little better as they’re controlled by the same Donor Class.