Colombia’s Left Faces Political Siege as Electoral Council and Courts Undermine Unity

Colombia is being internally attacked as part of the Venezuela threat. A commentator asked for reading material on Colombia a while ago, and I said at the time it is difficult as Colombia is divided. Now the results of that is becoming clear. The hegemon wants its backyard back. This is detailed and perhaps difficult to understand.

If you don’t get it, get the final sentence.

And if the institutions won’t listen?

Then it’s time to build new ones.

Colombia’s Left Faces Political Siege as Electoral Council and Courts Undermine Unity

The leftist coalition sabotage unfolds as Colombia’s National Electoral Council obstructs the Pacto Histórico while courts overturn convictions of far-right leaders tied to paramilitarism.

Colombia’s leftist coalition sabotage intensifies as the CNE blocks the Pacto Histórico and courts free Uribe — exposing deep judicial bias and electoral manipulation.

Related: Bolivia Backs Colombian President Petro After Trump Sanctions

On Sunday, October 26, 2025, Colombia held a pivotal primary consultation intended to unify the country’s fragmented left under a single presidential banner. But what should have been a moment of democratic consolidation turned into another chapter in a deepening political crisis — one marked by institutional obstruction, judicial reversals, and growing fears that the nation’s progressive movement is being systematically dismantled from within.

At the heart of the turmoil lies the Historic Pact (Pacto Histórico), the coalition led by President Gustavo Petro, which sought to formalize its internal unity ahead of broader elections in March 2026. However, decisions by the National Electoral Council (CNE) have thrown the process into legal limbo, effectively blocking the coalition from registering as a unified political party — a move that could disqualify its winner from participating in the upcoming Broad Front (Frente Amplio) primary.

“This isn’t just bureaucracy — it’s sabotage,” said Senator Iván Cepeda, one of the leading candidates in the consultation. “There must be total clarity: we’re participating under the guarantee that we’ll go to March.”

National Electoral Council of Colombia – Official Resolutions

A Coalition Under Fire

For months, progressive forces in Colombia have faced relentless pressure from multiple fronts. The U.S. revoked President Petro’s visa earlier this year, a rare diplomatic rebuke widely interpreted as political retaliation. At the same time, conservative sectors have weaponized the judiciary and electoral institutions to weaken the left’s momentum.

The latest blow came from the CNE, which refused to recognize the Historic Pact as a single party despite formal merger requests from key organizations: the Polo Democrático, Partido Comunista Colombiano, Unión Patriótica, Minga Indígena Social y Popular, and Progresistas, a breakaway faction led by Senator María José Pizarro.

The CNE excluded Colombia Humana for allegedly lacking quorum, Progresistas for lacking legal status, and offered no explanation for rejecting Minga Indígena.

This ruling transformed the October 26 consultation into an “inter-party” rather than “intra-party” process — a distinction with major consequences. Only parties with full legal recognition can feed candidates into larger coalitions like the Broad Front.

“They’ve killed the Historic Pact consultation,” declared Daniel Quintero, former mayor of Medellín and a contender in the vote, who subsequently withdrew from the race. “It’s clear the right wants to prevent us from uniting next year. I won’t fall into that trap.”

Former Health Minister Carolina Corcho, another candidate, vowed to continue: “We remain firm in our participation in the October 26 consultation.”

But without legal backing, her campaign — and those of others — faces an uncertain future.

Truth Commission Report – Victims of Paramilitarism in Colombia

Power Behind the Curtain: The Shadow of Álvaro Uribe

The CNE’s controversial decision was spearheaded by Álvaro Hernán Prada, its president and a member of the Centro Democrático, the far-right party founded by former President Álvaro Uribe Vélez.

Prada is currently under investigation for alleged witness tampering and judicial intimidation against Justice Minister Eduardo Montealegre — allegations that fuel widespread doubts about his impartiality.

His leadership at the helm of Colombia’s top electoral body has raised alarms among civil society groups. The Electoral Observation Mission (MOE) has long warned that the CNE suffers from partisan quotas, compromising its independence and transparency.

“The system is designed to favor traditional parties,” said MOE spokesperson Ana María Ospina. “When judges are appointed based on political loyalty, not merit, democracy becomes a rigged game.”

Seven of the nine CNE magistrates supported the decision — most affiliated with opposition or traditional parties, including Liberal, Conservative, Green Alliance, and Centro Democrático members.

MOE – Mission for Electoral Observation in Colombia

Judicial Impunity: Uribe Walks Free

While the CNE blocked leftist unity, Colombia’s judiciary delivered another shock: the full acquittal of Álvaro Uribe on charges of bribery, procedural fraud, and witness intimidation.

Uribe, sentenced in August 2025 to 12 years of house arrest for attempting to discredit Senator Iván Cepeda, walked free after the Bogotá Superior Tribunal overturned the conviction.

President Petro denounced the ruling as a green light for impunity:

“This grants protection to politicians who rose to power allied with narcotrafficking and unleashed genocide in Colombia.”

The case dates back to 2012, when Uribe accused Cepeda of offering benefits to witnesses in exchange for testimony linking him and his family to paramilitary networks.

Instead, evidence emerged that Uribe himself helped create and finance the Bloque Metro, a paramilitary faction of the AUC (United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia), from his family estate, Hacienda Guacharacas in Antioquia.

Juan Guillermo Monsalve, a former paramilitary serving over 40 years, testified that the Uribes were directly involved.

In May 2024, prosecutors formally charged Uribe, arguing he orchestrated a scheme to manipulate justice by forcing retractions from key witnesses.

Yet in October 2025, three judges reversed the conviction without addressing the core evidence. The ruling emboldens Centro Democrático to reposition Uribe as a Senate candidate in 2026.

“Álvaro Uribe will be number 25 on our list,” declared party president Gabriel Vallejo.

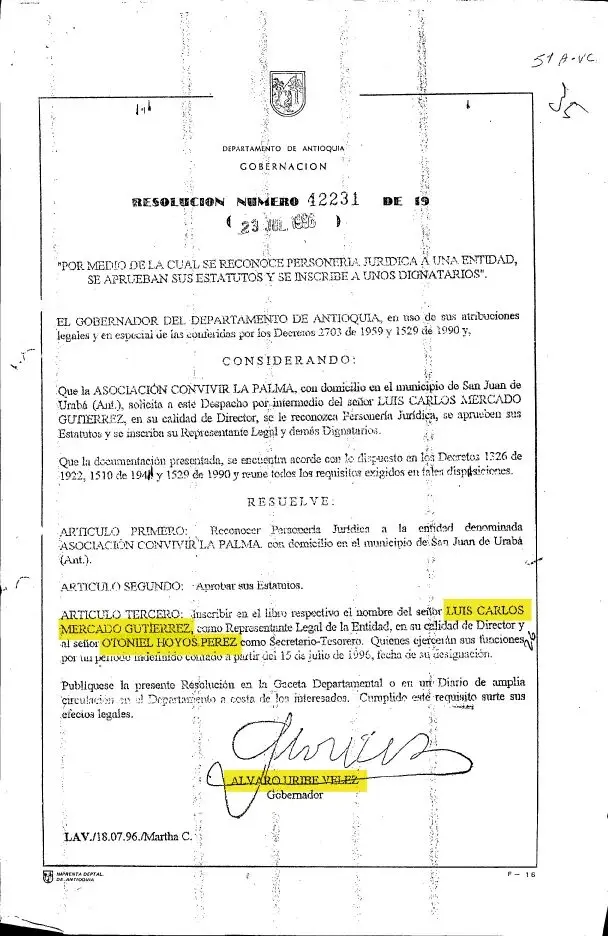

The Convivir Legacy: Paramilitarism Legalized

Central to understanding Uribe’s rise is the Convivir system — rural security cooperatives created during the presidency of César Gaviria and aggressively expanded by Uribe during his tenure as governor of Antioquia (1995–1997).

Though presented as civilian auxiliaries to the military, many Convivir groups became recruitment fronts for paramilitaries.

To establish a Convivir, three approvals were needed:

- Legal personhood from the governor (Uribe)

- Military endorsement

- Operating license from the Superintendency of Private Security

Uribe signed personhood documents for numerous groups led by known paramilitary commanders. He later defended the system before the Constitutional Court, ignoring links to massacres like Mapiripán (1997) and Tocaima (1997).

Under his leadership, Antioquia saw 69 Convivir groups — part of a national network exceeding 600.

According to Colombia’s Truth Commission, between 1995 and 2004 — the peak of Uribe’s influence — 45% of all conflict-related victims were recorded, with paramilitary groups responsible for 205,028 deaths and 63,029 forced disappearances.

Antioquia, Uribe’s home department, suffered the highest toll: 125,980 victims.

Miami Honors a Controversial Figure

Even as Colombian courts absolve him, Uribe enjoys growing honors abroad — particularly in Miami-Dade County, Florida, where pro-Uribista groups have successfully lobbied local officials to name streets in his honor.

In August 2025, Commissioner Roberto González announced a new “Avenida Colombia” tribute to Uribe — coinciding with his judicial release.

This follows earlier tributes: in 2020, a stretch of SW 117th Avenue was renamed “Álvaro Uribe Way”, and in 2021, “President Álvaro Uribe Way” was inaugurated in Hialeah, with Uribe attending via video call.

These gestures normalize a figure implicated in mass atrocities — and reveal transnational support networks for Colombia’s far-right.

Tactical Retreat: Parties Withdraw Legal Status

In response to the CNE’s restrictions, the Communist Party and Unión Patriótica formally withdrew their legal status from the CNE, Registraduría, and Procuraduría — a tactical retreat to preserve autonomy and avoid future sanctions.

Gabriel Becerra, head of Unión Patriótica, said the move ensures the Pacto Histórico can still participate in the Frente Amplio primary.

Jaime Caicedo of the Communist Party stressed this is not a break, but a protective measure.

As a result, the Polo Democrático Alternativo will now hold the consultation alone, determining its own representative — not a unified leftist standard-bearer.

Petro’s Counteroffensive: A Call for a New Constitution

Faced with institutional siege, President Petro has shifted from reform to revolution. He called on the people to enter “constituent mode” and collect 2.5 million signatures to convene a National Constituent Assembly.

“If they block every path within the system, we must change the system itself,” Petro declared.

The proposed assembly would draft a new constitution incorporating long-demanded social reforms: land redistribution, environmental protection, healthcare expansion, and demilitarization.

Petro confirmed he intends to run in elections for the constituent body — positioning himself as both president and revolutionary.

He predicted that progressive forces will triumph in the 2026 presidential and legislative elections, despite current setbacks.

A Regional Pattern of Democratic Erosion

Colombia’s crisis is not isolated. Across Latin America, right-wing sectors — often backed by U.S. interests — use judicial coups (lawfare), media smears, and electoral manipulation to weaken or remove leftist leaders.

From Brazil to Mexico, Ecuador to Honduras, the playbook is the same: criminalize dissent, control institutions, and delegitimize reformist agendas.

What happened to Lula, Dilma, Bachelet, and Morales is now unfolding in Colombia.

The international community must recognize what is happening: a soft coup disguised as legality.

Conclusion: The Fight for Colombia’s Future

October 26, 2025, may go down as the day Colombia’s left was tested like never before.

Blocked by courts, sabotaged by electoral councils, and mocked by foreign tributes to a disgraced ex-president, the movement faces unprecedented challenges.

But it also has something powerful: a base of millions who voted for peace, justice, and dignity in 2022.

They know the stakes. They have seen the graves. They carry the trauma.

And still, they march.

Because in the end, no court ruling, no electoral trick, no street named in Miami can erase the people’s will.

And if the institutions won’t listen?

Then it’s time to build new ones.

a couple of weeks ago i met a man that i assumed was venezuelan employed in the picture framing department of an art supplies shop. his english was flawless, he was amiable & obviously a first rate picture framer. turned out he wasn’t venezuelan but colombian & only recently settled… Read more »