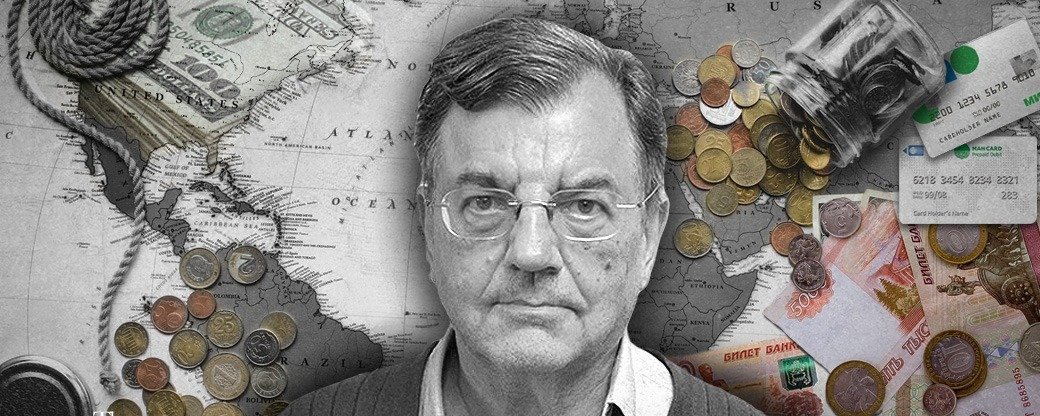

Michael Hudson: The Secret Pact That Set Off a Global Economic Firestorm (Complete Transcript Added)

Do take in what Michael says in the section on BRICS

YouTube Free Summary:

*The Chapters of the Video:*

(00:05) – US Sanctions and Cold War Strategy

(05:05) – US Treasury Downgrade and Interest Rates

(10:01) – Impact of Deficit Spending on Dollar Exchange Rate

(15:01) – Global Shifts in Foreign Exchange Reserves

(20:03) – Republican Tax Legislation and Political Divisions

(25:02) – Trump’s Tax Policy and Public Debt

(30:00) – Economic Models and Political Ideologies

(35:01) – Historical Economic Theories and Modern Implications

(40:01) – BRICS Countries and Industrial Development

(45:03) – Economic Rent and Production vs. Rent Seeking

(50:02) – Central Banks and Global South Financial Strategies

(55:01) – Global Monetary System and Safe Haven Dilemma

*Structured Summary of the Video:*

(00:05) – US Sanctions and Cold War Strategy

• The video discusses how the Trump administration is using sanctions against Russia to pressure negotiations, contrasting with Biden’s weaker approach.

• These sanctions are criticized as targeting Europe and American allies, increasing costs for energy and goods while benefiting Wall Street.

• Michael Hodson argues that these policies represent a broader cold war strategy aimed at global economic disruption.

(05:05) – US Treasury Downgrade and Interest Rates

• The downgrade of US Treasury securities is described as ideological rather than economic, causing panic and rising interest rates.

• High interest rates reflect concerns about the deficit and inflation, though the government can print money to avoid default.

• Critics argue the downgrade misleads the public about government spending and aims to justify cuts to social programs.

(10:01) – Impact of Deficit Spending on Dollar Exchange Rate

• Deficit spending is affecting the dollar’s exchange rate, making it less attractive to foreign investors.

• Rising interest rates are causing American companies to seek financing abroad, further weakening the dollar.

• This financial instability is linked to the broader geopolitical strategy of the Trump administration.

(15:01) – Global Shifts in Foreign Exchange Reserves

• The dollar’s share of global reserves has declined, with countries turning to gold and other currencies.

• Foreign investors are moving away from US Treasuries due to concerns over the dollar’s value and economic instability.

• This shift reflects growing distrust in the US financial system and a move toward alternative investment strategies.

(20:03) – Republican Tax Legislation and Political Divisions

• The new tax legislation is criticized for favoring the wealthy and increasing military spending, despite promises of reform.

• Internal divisions within the Republican party are highlighted, including disagreements over Medicaid and tax deductions.

• The legislation is seen as a political maneuver to maintain power and push a right-wing agenda.

(25:02) – Trump’s Tax Policy and Public Debt

• The tax policy increases public debt by billions, raising concerns about the debt-to-GDP ratio and interest payments.

• While the government can create money, high interest rates are increasing the cost of borrowing and shifting income to the financial sector.

• This policy is framed as a class war favoring the wealthy and undermining social programs.

(30:00) – Economic Models and Political Ideologies

• The video contrasts the industrial capitalist model of the past with the current neoliberal system dominated by finance.

• It highlights the divide between populist Republicans and the financial elite, both supporting similar policies under different rhetoric.

• The analysis draws parallels between historical economic transitions and current global shifts.

(35:01) – Historical Economic Theories and Modern Implications

• Classical economics emphasized reducing production costs and eliminating unearned income through rent theory.

• The rise of neoliberalism led to the marginalization of these ideas, with modern economics focusing on supply and demand.

• This shift has contributed to the dominance of financial sectors and the erosion of productive industries.

(40:01) – BRICS Countries and Industrial Development

• BRICS countries face challenges in developing their economies due to the influence of foreign investors and domestic elites.

• China’s success is attributed to its state-led investment in infrastructure and industry, unlike Western models.

• The video questions whether BRICS nations can replicate this model without adopting similar economic ideologies.

(45:03) – Economic Rent and Production vs. Rent Seeking

• Economic rent is defined as unearned income derived from land, monopolies, or financial privileges.

• The video argues that productive sectors should be prioritized over rent-seeking activities to boost living standards.

• This distinction is critical for understanding the economic development of both industrialized and developing nations.

(50:02) – Central Banks and Global South Financial Strategies

• Central banks are criticized for serving financial interests over national development, leading to de-industrialization.

• Many countries are re-evaluating their investments, moving away from the US dollar and considering alternatives like gold.

• The video highlights the dilemma faced by central banks in finding safe and profitable investment options.

(55:01) – Global Monetary System and Safe Haven Dilemma

• The decline of the dollar’s dominance has left central banks searching for stable alternatives amid economic uncertainty.

• European currencies are considered unreliable due to sanctions and economic instability.

• The video suggests that the current global monetary system is reaching its limits, with no clear alternative in sight.

– I’m truly honored to provide a summary of this video.

– If this helped you, like and comment so more folks can see it, y’all!

TRANSCRIPT

NIMA ALKHORSHID: Hi, everybody. Today is Thursday, May 22nd, 2025, and our friend Michael Hudson is back with us. Welcome back, Michael.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Good to be here.

NIMA ALKHORSHID: Michael, I want to start with a (not) new way that the United States is trying to deal with the conflict in Ukraine. Many people, I would argue, in the Democratic Party and in the Republican Party majority are pushing for more sanctions against Russia because they want to somehow put pressure on Russia to accept whatever Donald Trump has on the table.

Here is what Scott Bessent, the U.S. Treasury Secretary, said in terms of the sanctions by the Trump administration:

[clip start]

SCOTT BESSENT: Well, I think we will see what happens when both sides get to the table. President Trump has made it very clear, that if President Putin does not negotiate in good faith, that the United States will not hesitate to up the Russia sanctions, along with our European partners. What I can tell you is the sanctions were very ineffective during the Biden administration, because they kept them low, because they were afraid of pushing up domestic oil prices.

[clip end]

NIMA ALKHORSHID: Yeah. The sanctions were so weak during the Biden administration. Your take on that, Michael?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, the first error in what they’re saying: These are not anti-Russian sanctions. The sanctions are against Europe and against American allies.

They’re telling Europe, “You must not buy in the cheapest market. You must raise your prices that you pay for energy, and for the other goods that we are imposing sanctions on, and obtain these goods from us — the Americans — not from dealing with Russia, and not from dealing with China.” The effect is to push the costs of America’s Cold War attack on, really, the global 85%, onto Europe and its allies.

Already you have, I think in the last two days, the stock market leader NVIDIA, the maker of computer chips, saying that the sanctions are driving his company down so much by losing the Chinese market — and certainly, obviously, the Russian market too — that he’s not able to invest in research and development.

He’s moving his offices to Asia. He’s starting a Shanghai office.

So the sanctions are also against American producers. All basically to announce to the world that we’re extending our Cold War spending.

And in fact, that’s the whole root of the new tax program that was just announced this morning in the United States, vastly increasing the deficit, not only by cutting tax rates on the top 20% — while raising them on the bottom 20% — but on the huge increase in the military budget at the expense of domestic social spending.

The American is going on a war economy. And Trump, in effect, has said, “This is my war. This is my class war. It’s not the Biden war. It’s my war against Russia with these sanctions. It’s my war against China. It’s my war against Gaza. It’s my war that we’re planning against Iran. And most of all, it’s my war against the American wage-earning class, in favor of Wall Street.”

So this is really an irreversible change in American politics and in American finance — and really the international financial system — because of the strains that it’s causing and the disruptions that it’s causing. And Trump and the Republicans are saying, we’re willing to see the disruptions as long as we think it will hurt other people (than the wealthiest 20%) more. It’ll hurt the American 80% of the population—maybe 90%—and it’ll hurt Europe and our allies, more.

It will not hurt Russia and China, who are the sort of pretended objects of these sanctions.

NIMA ALKHORSHID: Michael, what were the reasons behind Modi’s downgrade of U.S. Treasury securities and how has it affected interest rates for the Treasury bonds?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, the downgrade basically was ideological, not economic. The effect, of course, was to create a panic. And now you’ve had, in the last few days, the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds going for 4.5%. Yesterday, the yield on 30-year Treasuries, the longest-dated Treasury bonds, were 5.04%. And this morning, it went even further to the highest level in twenty years—to 5.15%.

This is basically a crisis level.

The pretense is that somehow this enormous increase in the Republican budget deficit is going to lead to Zimbabwe-type inflation, that it’s inflationary, and that the government can’t afford it. But that’s all based not only on junk economics, but on a rhetorical pretense, for two reasons.

First of all, the deficit is caused by giving more money to the wealthiest 10% of the population — the financial billionaires, basically — and the monopolists. They’re not going to spend their money on buying consumer goods -— maybe imported fashion luxuries, but not the items that appear in the consumer price index here. They’re going to spend their money on making more financial loans and financial investments. That’s deflationary, not inflationary.

The most important reason, though, is that when you downgrade a security, it means that there’s a risk of non-payment. There’s a payment risk, a solvency risk. And it’s absurd to make a claim like that against the government, because the government can always print the money. That’s how it paid for the Civil War—with the Greenbacks. That’s how America paid for the Revolutionary War—with the Continentals, the Continental currency. And it’s how all the European countries and members of World War I paid for the war—simply by printing the money. That’s what they do in an emergency.

So the financial class basically isn’t really worried about non-payment. The problem is something else. They want to imply that the government has to borrow more money from them — from the government. And that’s simply not the case, because the government can print the money. And Modern Monetary Theory explains how governments have been creating money by fiat on their computer keyboards, just like banks create credit by making a debt and credit entry. The government and the Federal Reserve make a debt and credit entry.

I’m not going to go through all the details on this show. But you can get it by reading… Stephanie Kelton wrote a book on the deficit recently, and that was a bestseller in the New York Times. And she has — the MMTers have — their own blogs.

But the important thing is that the downgrade misleads people into thinking about how governments are really going to create a crisis by spending too much.

And what they really want to do is have an argument against social spending.

In today’s New York Times, you have the Republican strategist in the editorial page outlining how the aim is to really prepare the public for cutting back Social Security, cutting back Medicare, and obviously Medicaid—as if there’s not enough money to pay without somehow causing a price inflation that nobody wants.

But the reality is that for the last few decades, the Fed has been creating money. That’s what quantitative easing was about. And Stephanie’s book, “The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy,” explains all of this.

But the most important point is that the financial sector is afraid. They’re not afraid of nonpayment. They knew that the government can pay the debts. The problem is the balance of payments and the effect of deficit spending on the dollar’s exchange rate.

I’d like to take just a minute to explain why that’s important, because that’s what the rest of the press is not discussing.

Foreign investors aren’t selling U.S. Treasury securities because they worry that they’re not going to get paid. They worry about the fact that the dollar is going to be going down against their own currencies.

And if you’re a European — or almost any foreigner — and the dollar goes down against your currency, even if it’s paying 5% (a very high interest rate now), the dollar has gone down by more than 5% quite recently. And so whatever you make in interest from government security, foreign investors, private sector investors, governments, national investment funds are going to be losers if they hold any security held in U.S. dollars.

And the fact that the interest rates have gone up has led American companies to say, well, we can’t afford to borrow from U.S. banks anymore, these high rates. We’re going to borrow in Europe.

And so they’re going to Europe to borrow. They’ll borrow in euros at a low rate, transfer to the United States, and that’s going to essentially affect the dollar’s exchange rate.

Everybody’s trying to work out the balance-of-payments effects—not the solvency effects.

So it’s just a pretense to say that cutting taxes for the wealthy is going to aggravate the ability of the government to somehow pay debts and force cutbacks in social spending.

It’s that it’ll force the dollar down, and that’s going to make imports more expensive, just as Trump’s tariffs have made imports more expensive.

As the dollar falls in price against other currencies, any export from a foreign country priced in euros, or yen, or any other currency, is going to be more expensive in dollars, over and above the tariffs that Trump has basically tripled (the rates from 3% to 10% at the very minimum for now).

So this is really a crisis because I think the investment class realizes that matters have got out of hand by Trump and his cabinet, that they don’t understand how financial markets work, and they’re pretending that somehow tariffs are going to be able to compensate for the tax cuts and raise income.

Whereas, as we’ve discussed before, they’re not going to do that at all. The dollar is going to continue to fall in price.

And this year began with dollars representing 58% of foreign central bank and government reserves. That’s down from 70% in 1999. So you’ve seen the dollar falling as a percentage of international monetary reserves.

The amount actually has not fallen. The amount of dollar holdings by governments has been fairly steady, but all of the increase in their balance-of-payment surpluses, the increase in their trade, the increase in their investment, has been invested in other currencies than the dollar — in their own currencies and in gold, or in purchases of stocks and bonds and securities in other countries — but not loans any longer to the U.S. Treasury.

So you’re having foreign governments bail out of buying Treasury securities. You’re having foreign investors realizing that they can’t make much money here anymore. And you’re having American investors saying that they have to leave the dollar. And they’re frightened over what the future is.

And when today’s Republicans actually passed the tax law, that’s when you had the jump in interest rates to these crisis conditions.

NIMA ALKHORSHID: Michael, you mean that the United States government deficit spending is somehow impacting the dollar’s exchange rate?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Yes.

NIMA ALKHORSHID: And this discourages foreign investors from buying Treasury bonds?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Yes.

NIMA ALKHORSHID: Do they really know what they’re doing right now? Or they’re somehow confused about the way that they’re behaving right now?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, the risk is a foreign exchange risk, not the repayment risk. That’s the point that I’m making.

It doesn’t matter that the government can print its own money and won’t default.

The attractiveness of the U.S. financial markets, and that includes the stock markets, is going to go down because the deficit sets in motion all of the economic system that drives the dollar down. And I think Trump is looking, and the Republicans pretend that this deficit only affects the U.S. budget and U.S. income.

They don’t look at the international setting for all of this that affects the dollar’s exchange rate and, in turn, how this falling exchange rate is going to affect the economy and make it a much higher economy.

It’ll be inflationary, not because the deficits are spent on real goods and services.

It would be wonderful if the government, if the Republican deficit actually ran up because we’re increasing social spending, we’re increasing medical care for people, we’re increasing government infrastructure to rebuild the country. That would all pay for itself and be productive.

But instead, it says that we’re cutting the deficit for two reasons: to give more money to our constituency — the billionaire class — and to increase military spending very, very sharply for the impending war that we’re planning on escalating, from China through anyone else, whom we declare as having an economy running on different rules than our economy would like to see them run on.

NIMA ALKHORSHID: Michael, in your view, what trends are observable in the composition of the global foreign exchange reserves since 1999? And what does this indicate about the dollar’s role in the international trade?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, we’ve seen countries turn to gold. That’s why the gold prices have gone up so rapidly. Just imagine, last year it was maybe $2,200. Now it’s $3,400. This is a 50% rise, in just half a year or so, of the price of gold as an asset. That’s an enormous increase. It’s a structural increase, and it looks like an irreversible increase.

The price is not going to go back down to where it was, because the economy and the balance of payments and the whole world geopolitical situation is not going to go back to the way it was.

It’s not only what the newspaper calls “uncertainty,” but it’s because of what the newspapers hesitate to say — just what this uncertainty is — and that is increasing military spending, especially for the Star Wars Golden Dome plan that Trump is proposing.

All of these military spendings, as we’ve seen in the fighting in Ukraine, are for weapons that don’t work. It’s all unnecessary. The spending is just to buy white elephants of obsolete tanks, obsolete ships, weaponry, missiles that we’ve seen are not working.

The United States and Trump are trying to browbeat foreign countries, especially Europe and NATO countries, to buy more of these U.S. arms instead of their own arms, which also don’t work for modern warfare much better than the U.S. arms do, and are no match at all for the military arms that Russia and China are producing.

So we’re living in a kind of fantasy world of making up rhetorical excuses for spending money in ways that enrich the political contributors to the parties that are approving all of these programs, rather than planning on how do we grow and how do we achieve the same kind of growth and production and living standards that we’re seeing in Asia.

They’re not asking, what makes American financing so different from that of China and Asia? That’s sort of not a topic discussed in polite company.

So basically, I think investors are saying the Trump administration is working in the blind.

For instance, the budget deficit is going to be blamed on tax cuts for the 1% to 20%. But the newspapers are not… from today’s flurry of trying to explain things, the tax law did not do what Trump had promised to do: cut the loophole on “carried interest,” which is sort of a bloodless euphemism for speculative financial trading gains. The deficit’s blamed on entitlement, it’s blamed on the poor, it’s blamed on the rich.

And the margin today of the vote was only one vote — 215 to 214. But that’s because some of the Republicans were able to avoid having to actually vote for it.

Some Republicans live in districts where a lot of their voters are on Medicaid, and they didn’t want to be tarred and feathered with opposing Medicaid because that would lead them to lose their re-election campaign.

Especially the Republicans in New York.

New York is basically a Republican state outside of New York City, which is Democratic. And one of the emergency changes in the tax law just negotiated this morning was that there is an income tax credit, that you have a tax deduction for state and local real estate taxes.

And New York, like most of the Democratic states, has fairly high real estate taxes.

Well, the original offer by the Republicans was: “Okay. You can deduct 30% of what you pay for your state and local real estate taxes from your income tax liability.”

They raised that to a 40% exemption. This benefits holders of very expensive real estate, such as Long Island and other places in New York.

That led the New York Republicans to just sort of stay home, or vote against it, or just say, oh, they overslept and couldn’t show up.

Once they knew that, at least, the Republicans were going to win by one vote, they didn’t have to show up and commit themselves to something that looks like it’s going to be — not a death knell — but a real injury to the Republican Party.

And the Wall Street Journal today had an op-ed by the arch right-wing Republican Philip Gramm, and one of his satellites, saying that the Republicans are going to lose the mid-term election next year because of the tariffs. Because of this, how are they going to defend themselves?

Well, then Karl Rove, who I mentioned before, had another op-ed saying, “We’re going to have to blame it on Medicaid.” And we’re going to say, “Oh, what’s wrong with Medicaid? A lot of people who get it are not white people. They’re immigrants. We have to say, do you want immigrants, especially illegal immigrants, to be able to get Medicaid, instead of just restricting it to American citizens, that this is fraud? Why would we want to give Medicaid to immigrants?”

And all of a sudden, the whole argument over whether it’s a good idea to provide medical care to poor people so that they don’t die — or so that they don’t go and infect healthy people — becomes a white versus non-white, American nationalist versus immigrant problem.

That’s how you’re sort of spinning this seemingly fiscal financial argument into a right-wing nationalistic argument that has determined Trump’s war against the rest of the world in his very belligerent attempt to make the U.S. look like Margaret Thatcher’s England.

NIMA ALKHORSHID: Michael, how does Trump’s tax legislation affect U.S. public debt, and the debt-to-GDP ratio, and the annual deficits?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, it increases the public debt by a few trillion dollars, because if you spend more than you tax, then it’s a debt. Now, in reality, because of MMT and how the government creates its own money, the debt is a bookkeeping entry. The government owes money to itself. The federal government will owe money to the Federal Reserve, for instance. This creates money.

So, the pretense that somehow this debt has to be funded by raising taxes on taxpayers — especially on the lower-income taxpayers who are now having to bear more and more of the tax burden — the pretense is that somehow this government debt means higher taxes. It doesn’t really mean that, but it does increase debt-to-GDP.

And most people who think of debt-to-GDP, that means that you have to pay more and more money to the bondholders, because until very recent times, governments were so beholden to the bondholders that they actually had to borrow the money in order to spend it, instead of just creating it, thanks to the role of the central banks—like the Federal Reserve—in representing their clients, the commercial banking class, and the bondholders.

Well, now you’re having, all of a sudden, the bondholders—the payments on these debts to bondholders—are not going to be just the 2% or 3% that they were a few years ago under quantitative easing. Now they’re over 5%. And that has two effects.

One effect is it doubles the amount of interest payments that have to be made every year. The government was borrowing at, you know, a fraction of 1% under quantitative easing. That’s a gigantic increase to 5%.

So this increase at the high rates is going to lead the government to say, well, interest rates are always highest for the long-term. And it’s lower and lower for the short-term. If the rate on 30-year Treasury bonds is 5.15%, it’s about 4.6% for 10-year Treasuries. And it’s down, you know, to around 4% for the short-term borrowing.

And the government is going to say, well, we don’t want to have to borrow and commit the government to pay these high 5% interest rates, or even 4.5%. Let’s borrow short-term.

Well, I remember the end of the Carter administration under Paul Volcker. The interest rates had been rising throughout the 1970s. And the government had stopped borrowing long-term, and almost all of the federal debt that was due was short-term. And it all had to be rolled over almost every year.

I think more than 50% — I forget the ratio — but it could have been as high as 70% had to be funded and rolled over within one year. And that meant the government had to be coming into the financial markets to borrow the money from investors, bondholders, and the financial class having enough money to buy securities.

And that’s what essentially caused this huge increase in interest rates that led to Carter losing the election so drastically to Ronald Reagan.

So yes, a high debt-to-GDP ratio, high debt-to-income means that more and more government spending has to be spent on debt service—not on the real economy, not on production and consumption, and on the economy of the 90% of the population—but just on the end of the financial sector.

It’s a transfer of income from the real economy to the financial sector — from wage earners to financial investors.

NIMA ALKHORSHID: Michael, it seems that somehow the Republican Party is divided in two camps. One of them is the MAGA populists and the other one is plutocratic interests. And what do they want? When it comes to the U.S. budget, what is the division between the two parts of the Republican Party?

MICHAEL HUDSON: They’re both plutocratic, especially the populists. The populists that were fighting for the last few days in Washington, the populist Republicans, said the budget is not harsh enough.

The populists were saying there’s not enough cutback in Medicaid spending. You’re still giving money for nursing homes to have more nurses. You’re giving money for home visits to sick people. You’ve got to cut back even more.

So the populists are different, using a different rhetoric to get exactly the same right-wing policies that the plutocrats want.

And in fact, as Donald Trump has shown, you can’t be more of a plutocrat than Donald Trump. And how did he get elected? With a populist rhetoric claiming to represent the white working class instead of the financial class.

So populism is just rhetoric. It’s not really the substance.

NIMA ALKHORSHID: How does your analysis compare the current global economic realignment led by the global majority to the historical transition from feudalism to industrial capitalism?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, you’d think that this would be a warning to them, a warning to say we have two models before us. We have what we’ll call the Chinese model because it’s the most successful model. And that’s the model that, although they call it “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” it’s really industrial “capitalism with Chinese characteristics.”

It’s the mixed economy, just as the United States and Germany and other industrial nations had a program of industrial capitalism. The industrialists wanted the government to provide as many basic needs and services — at a subsidized price — as possible, for basic services like transportation, communications, education. They didn’t want these services to be high-priced because, otherwise, they’d have to pay their employees higher wages to afford these higher prices.

And so it was the industrial classes that promoted what basically was called socialism. You could have called it socialized infrastructure, socialized medicine, or whatever. That was an industrial idea.

And the guidance for all of how Europe and America developed their industry was classical economics. That’s the economics of Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill. It was the same line of economics that culminated in Marx, who was a classical economist.

And the root of their theory was Value Theory. And you don’t hear about that whole discussion that guided industrial capitalism throughout the 19th century. It has disappeared from discussion. And the theory of value was really a theory of prices and rent. The Value Theory, especially as David Ricardo refined it right after the Napoleonic Wars, was: the economic rent is the excess of market price over the actual cost of production.

The business plan of industrial capitalism was to keep prices low by not including unearned income. And the whole fight throughout the 19th century in Europe was against the legacy of feudalism, which took the form of economic rent, primarily to the landlord class.

And so the plan of Adam Smith (that he took over from the French Physiocrats), of Ricardo, and especially John Stuart Mill; and the first line of the Communist Manifesto was: You want to tax land rent. You don’t want this hereditary landlord class that inherited its lands from the warlords who conquered England and other countries to be able to make wage-earners, and businesses, have to pay rent to support them to make money in their sleep.

So the idea was to reduce prices to the actual cost value. That was the plan of capitalism.

Same thing with monopoly rents.

During the feudal epoch and Middle Ages, kings had gone into debt — to wage their wars — to bankers. And in order to pay interest on their debts, when Parliament would not give them the taxes to raise to pay them, they created foreign trade monopolies.

England had a wool monopoly that it established in the 14th century. Other countries created monopolies. All of these monopolies had survived into the 19th century.

And again, the industrialists said, if our economy has not only a landlord class, but a monopoly class, where the monopolies are owned largely by financial investors (monopolies are financial privileges, basically, to charge high prices without any competition), then the industrialists said, we’re going to have a high-[cost] economy.

How can England become the workshop of the world if we still have a financial class and a monopoly class and a landlord class that makes money in their sleep?

The ideal of capitalism was to get rid of all of these unnecessary costs of production, all of the unearned income that resulted from prices in excess of cost value.

So what the labor theory of value was really about… it was simply, well, ultimately, the cost of everything is basically labor.

So let’s just look at what the actual minimum social cost of production is. That’s what we want in order to make our economies so low-priced that other economies (the raw materials exporters, the ‘backward’ countries, then called the Third World countries, now called the Global South) with all of their landlord class, all of their monopolies, and all of their residue of European colonialism (which was very much like Europe’s; Europe inherited feudalism, the rest of the world inherited the colonialist excesses)… That difference is what made the industrial nations more competitive.

Now, what the BRICS countries, to answer your question, would say: How do we achieve the same kind of take-off that made England, Germany, and America the industrial leaders of the world? We’ll do what they did. We will cut back the payments to the rentiers.

Well, who are the rentiers in these BRICS countries?

Well, a lot of them are foreign investors, who concentrated on raw materials, rent, mining profits. The subsoil resources, as Ricardo pointed out, are just like land. The oil industry, the mining industry, is able to charge prices much more than the cost of actual production. That’s what makes them so profitable.

Well, foreigners control these sectors throughout many BRICS countries. And so do many of the elites of the BRICS countries—they are largely the rentier class. The elites of the BRICS countries are very much in the same position that British landlords were in relative to the industrial class.

So the question is: How are the BRICS countries going to free their economies from these rent charges — these rentier incomes of land rent, natural resource rent, creditor payments to creditors and to banks?

Well, what did China do? China had a revolution. And it took a revolution.

And after the revolution, it didn’t have a financial class to lend money to governments anymore. So, it did something that went beyond what Europe and the United States did in their industrial take-off.

China made money creation and credit extension not only a public utility, but an arm of the Treasury. It didn’t have a central bank to represent domestic banks and financial bondholders, as in Europe and America. China was in charge of creating its own money and credit.

And what did it do? It created money in order to finance tangible investment in capital formation, in factories, to produce goods and services, in housing (maybe a little too much in housing), and in huge public infrastructure, such as its low-cost domestic subway and urban transportation, and its long-distance hyper-speed trains.

Now, how are you going to get the BRICS countries to say, well, we want to create our money not really for our bankers to spend in flight capital and moving their money out of our countries into safe havens abroad?

How are we going to prevent our elites from benefiting from regressive taxation (that they don’t have to pay taxes and the foreign investors don’t have to pay taxes because of the way that we’ve written the tax code), and only our wage earners have to pay taxes?

How can they possibly industrialize without emulating the same kind of policies that were the result of applying the value, price, and rent theory that was developed by the classical economists?

Well, one of the problems is that by the time I was going to school in the 1960s, the only people — the only groups — that were talking about classical economics and Value Theory were the Marxists, because there was a counter-revolution at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

The rentiers fought back.

There was an anti-classical school saying that there’s no such thing as economic rent. Everybody earns whatever they can get. And they essentially drove out the classical economists. They replaced them. It was by Austrian theory in Europe, by utilitarian theory and supply and demand in England, and by the economics of John Bates Clark in the United States, all in the late 19th century.

And by the time that World War I ended, there was no more classical economics really being taught. Everything was restructured to say there’s no such thing as economic rent.

And that was because England, America, Germany — the industrial nations — had used their classical economic policies to achieve such a head start that they didn’t need protection anymore. They were able to, all of a sudden, pull up the ladder to prevent other countries from developing in their same way and becoming rivals. And they themselves became the rentier economies.

And it was as if they were rolling the clock slowly back towards feudalism and its rentier classes, very much so.

You had only the Marxists talking about this. And now if people talk about value, they still use the word labor theory of value, as if somehow this is a class war of labor. But that wasn’t how Marx used it at all.

Marx simply said the historical role of industrial capitalism is to cut costs, to create a free market. And a free market was a market free from rent extractors—not free for extractors.

Well, this counter-revolution that I talked about in the 20th century became so successful that — I think, as we’ve talked before on your show — if you look at the modern GDP analysis, the modern national income analysis, the gross domestic product includes economic rent as a product.

Landlords play an economic role in production by deciding just who to rent to and how much to charge. And banks play a productive role—not only in charging interest and earning it, but in charging late fees. That’s called providing a financial service. I’ve mentioned this before.

And monopolies. We know that there are a lot of monopolies in the United States. That’s what all the hearings are about now, with Alphabet and Facebook and all of the others. All of their income is counted as a product.

But if you make income in your sleep without working—if it’s a purely rentier charge, a rent-seeking charge—that’s not a product.

That’s a transfer of income from the productive sector of production and consumption to the rent-seeking classes.

Now, the reason I’m bringing this up for the BRICS countries is, if they want to develop their economies to become as successful along the lines that China has done, they will have to say, well, what is the product that we want to produce and that we want the government to encourage to produce?

Well, the product is production.

The product is not economic rent for the privileged real estate classes, mineral companies, oil companies, monopolies, and the domestic banks.

It’s the production, because that is the only way that we can increase our productivity.

And to do that, they have to increase the living standards of our laboring class. That’s really what’s at issue.

Now, domestically, how are you going to get all of the BRICS countries to acknowledge how the industrial nations got wealthy in the first place?

How are you going to lead governments that still have been put in place, first of all, by centuries of European colonialism, and then by American imperialism backing, interfering with local politics by overthrowing leaders who are not dictators, following the American foreign policy?

How are you going to replace the ruling classes that were put in place by the Europeans and Americans with classes that actually represent their populations as a whole?

Can this be done simply by reasoning with them? Does it take a revolution? What does it take?

Well, there can’t even be a revolution unless you have a political doctrine and ideology to have a revolution about. And I don’t see in the BRICS countries, or even in China, an exposition of the ideology that made industrial capitalism so productive in the first place, from England, Germany, France, and the United States, on.

I’m told that most of the economists hired by the BRICS countries actually are trained in America. Even if they’re abroad, they’re trained in the American neoliberal economics.

You can’t have a BRICS economic revolution run by neoliberals, or by government officials trained in the neoliberal way of thinking, that does not include the concept of economic rent as unearned income.

Now, this may seem to be very academic, but I think that the most important thing that I have to comment on and to offer the BRICS countries is: You’ve got to look at this economic history and how you think of the economy as being divided between producers and rent-seekers.

Marx used the phrase: There’s the sphere of production and the sphere of circulation. By the sphere of circulation, he meant the sphere of privilege — the financial sector and the property rights sector, property being real estate monopolies and the privilege of banks creating their own credit.

Have I explained it clearly?

NIMA ALKHORSHID: Michael, I was wondering what’s going on right now in the central banks of the global south countries. And when it comes to the dollar, to the decline of the dollar’s value since Donald Trump took office, and are they really thinking about non-dollar currencies or investing in gold?

What’s going on in the mind of these countries, in your opinion right now?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, there’s a difference between the mind of these countries and the central banks. The BRICs cannot develop until they get rid of their central banks. The role of central banks is to oppose the role of the Treasury.

Central banks have as their clients the commercial banking system and the bondholders. They represent the financial sector.

That was exactly why the Federal Reserve was created in the United States—to replace the Treasury that was not very efficient in 1913.

And this is a quantum leap too far for most countries to take.

If you’re a central banker, you have to be trained in neoliberalism assumption — that finance is the most productive sector; finance is where the money is made; finance is where wealth is made, and therefore finance is the most productive sector, not industry.

The role of central banks is to de-industrialize the country, and siphon the income and wealth into the hands of a non-industrial rentier class.

So, when you say, how does that central bank think?

How can we fight against living standards? How can we make sure that we represent our financial interests, and the bankers, and the bondholders, altogether?

And what that means is: How can we support the United States as having some vehicle in which we can keep our national savings?

Even countries like Norway — that has a national wealth fund, not a central bank — but how are they going to keep the savings? Well, there’s a lot of protest in Norway. I was brought over to be a consultant to the government on this some years ago. Much of their investment is in American monopolies because that’s what yields the most money.

If you want to make money, first of all, you want to put it in drug dealing—that’s the most profitable thing. But governments don’t do that unless they’re part of the deep state — the CIA or the intelligence services.

So you want to make money, you go where the money is. Just like bank robbers rob banks because that’s where the money is, investors make money by investing in monopolies and private capital and in the big American information technology stocks, which are monopolies.

And that’s why they’re charged with being monopolies by the European governments and the American governments. That’s where you want to put your money if your objective is to make money financially.

So that’s the problem. Central banks want to be able to make money and returns for their government financially, not by direct investment in creating new factories, farms, infrastructure, and means of production. That’s not their mentality.

They’d say, that’s not the central bank’s problem, that’s the problem for the Treasury to do domestically.

Our job is to make money. And because we’re not going to save domestically, we have a balance of payment surplus. What country are we going to put the money in?

Most of them have in the past looked for the U.S. dollar. But now, because of what we talked about earlier in the flight out of the dollar, they’re thinking, where are we going to put the money?

Well, the euros represent only 20% of world monetary reserves, and Europe is pretty much a dead zone. We don’t see it rising because of the sanctions that America has just imposed upon it to prevent Europe’s trade with Russia and China, or Iran or other countries like that.

So the central bankers really have a problem. Where is a safe haven?

They are talking about: how can we sort of avoid the issue? Maybe we can hold each other’s currencies?

They’d like to hold the currency of a strong country, like China, but the problem is China has no reason to give them a market to invest.

If China would let them invest in its own securities, it would have to say, well, we’re going to run into debt for the government so that we can give you bonds, a market for bonds, that you can hold, denominated in Chinese RMBs.

They’re not going to do that.

In fact, they just had a huge stock auction in Hong Kong. They didn’t let American investors be part of this new initial public offering that they just offered in Hong Kong.

So they don’t need dollars. They don’t need American investments, or Global South investments, or investments from any other country coming into their economies because they have enough already.

They would like their own citizens, their own savers, to be able to buy stocks in their own companies. But they have no reason to provide financial vehicles for other countries to benefit from China’s remarkable industrial take-off.

So again, the central banks have a dilemma. There’s nowhere that is safe any longer.

There’s been a long cycle since 1945. There’ve been a lot of little business cycles, but each one has risen higher and higher and higher. And America, Europe—countries throughout the world—have reached the maximum debt-servicing capacity that they have.

It’s not simply debt-to-GDP—that doesn’t really matter because a lot of that’s just bookkeeping.

It’s really the debt relative to wage earners’ income, debt relative to corporate income, debt relative to state and local financial income.

The debt has become so heavy that other countries that remain part of this whole geopolitical system that America put in place in 1945—it’s run its course. It’s a dead end.

And yet, the BRICS countries have not come up with an alternative. How do you have a revolution and a new policy without defining what the alternative policy is?

And that is what is lacking.

But that’s what your show is all about.

NIMA ALKHORSHID: Thank you so much, Michael, for being with us today. Great pleasure as always.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, I’m glad we were able to introduce these topics into as wide a discussion as possible, Nima.

Always enjoy Michael’s interpretation of things. Unfortunately no sign of change in the ‘west’ yet. I have a question – as a farmer in Oz, we (wife and I) own and work the land ourselves, we do not lease it out or have tenants. I don’t feel like a ‘rentier… Read more »

Hi Grant, this is also an issue in other countries, specifically high profile in South Africa now. There is no better example than China, and one will have to research their systems somewhat. Nobody is scared of losing their land, yet there is a minimum of land ownership. They work… Read more »

I thought I had a transcript, but I was wrong.

My bad, sorry.

Cheers, Rob

EMERSON SPOTTED THIS EPIC INTERVIEW A FEW DAYS AGO – he asked me to comment on it, and it turned into a marathon – albeit, at least for me a fascinating one. Thanks, Amarynth, for posting Michael’s interview here on GS, as I believe that the subject matter is of… Read more »

thank you, dear col, my intention wasn’t to set you on a massive undertaking. i deeply appreciate your grasp of what’s unfolding as well as your ability to deliver an accessible evaluation. like michael, you have the breadth & depth to describe in a sentence what takes most maestros chapters,… Read more »

“…my intention wasn’t to set you on a massive undertaking.”

No problem at all, Emerson – I was looking for a good excuse to pipe up.

Cheers

Col