Coexistence Not Co-Destruction: Remembering Bandung 70 Years On

Featured Image: Image credit: Dossier no. 87 ‘The Bandung Spirit’, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, 2025.

Tings Chak on the importance of cooperation among the victims of imperialist forces. South-South cooperation frameworks are receiving increased attention, together with renewed calls to strengthen cooperation and unity within the BRICS, RCEP, and other Global South multilateral platforms.

Background:

All that I need is that for peace

You fight today, you fight today

So that the children of this world

Can live and grow and laugh and play.

This was the essence of the Bandung Spirit. It was as simple as that. That essence permeates the ten principles, which were published in the conference’s final communiqué on 24 April 1955:

- Respect for fundamental human rights and for the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

- Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations.

- Recognition of the equality of all races and of the equality of all nations large and small.

- Abstention from intervention or interference in the internal affairs of another country.

- Respect for the right of each nation to defend itself singly or collectively, in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations.

(a) Abstention from the use of arrangements of collective defence to serve the particular interests of any of the big powers.

(b) Abstention by any country from exerting pressures on other countries. - Refraining from acts or threats of aggression or the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any country.

- Settlement of all international disputes by peaceful means, such as negotiation, conciliation, arbitration, or judicial settlement as well as other peaceful means of the parties’ own choice, in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations.

- Promotion of mutual interests and cooperation.

- Respect for justice and international obligations.13

Effectively, these principles argued for an international order rooted in the UN Charter (1945) rather than one based on the creation of military blocs and the use of military force to shape the world and subvert sovereignty. In his reflections on the Bandung Conference, Abdulgani suggested that it was a forum to ‘determine the standards and procedures of present-day international relations’ and that it championed coexistence instead of co-destruction.

By 1955, seventy-six countries had signed onto the UN Charter, which held treaty obligations towards its signatories; about eighty territories, including most of the African continent and a majority of the Pacific islands, remained under colonial control. The UN Charter was then, and remains now, the most important consensus document in the world; as countries gained their independence from the late 1950s to the 1970s, they joined the United Nations as full members.

There was, however, no consensus on the future towards which these countries were marching. Participating nations ranged from those in US military alliances (Turkey, the Philippines) to non-aligned states (Indonesia, Egypt, India), and included ideologically distinct regimes – from newly communist nations (North Vietnam and China) to those accusing Soviet communism of being ‘another form of colonialism’ (Ceylon, now Sri Lanka). In other words, it was unclear how unity could be built from such diversity.

In his opening speech, Indonesian President Sukarno emphasised that ‘colonialism is not dead’ and that it persists in new forms. He declared:

Colonialism also has its modern dress, in the form of economic control, intellectual control, and actual physical control by a small alien community within a nation.

Now these nations were united in their opposition to colonialism – ‘the lifeline of imperialism’ – to defend their hard-won independence. As former colonies:

This line [that] runs from the Straits of Gibraltar, through the Mediterranean, the Suez Canal, the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, the South China Sea, and the Sea of Japan. For most of that enormous distance, the territories on both sides of this lifeline were colonies; the peoples were unfree, their futures mortgaged to an alien system.

‘We have so much in common’, he added, ‘and yet we know so little of each other’.

Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai played a pivotal role by raising the banner of ‘seek[ing] common ground while reserving differences’, as part of the young communist country’s debut on the international diplomatic stage. One of the conference’s major achievements was the unanimous adoption of a ten-point ‘Declaration on the Promotion of World Peace and Cooperation’. These principles – including sovereign equality, non-aggression, non-interference, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence – have since become the cornerstone of Global South diplomacy.

Even before Bandung, the coups started.

A World of Coups

A few weeks before the Bandung Conference, in April 1955, US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles held a meeting with the British ambassador to the US, Sir Roger Makins. Dulles told Makins that he had been ‘considerably depressed’ about the ‘general situation in Asia’. This ‘situation’ was embodied by a speech made by Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister following its independence, in the Indian Parliament on 31 March 1955 in anticipation of the Bandung meeting, in which he attacked SEATO as a hostile pact, NATO for giving Portugal support to retain Goa in India, the apartheid regime in South Africa, and the West for ‘meddling’ in West Asia. Nehru’s speech, Dulles said, ‘had taken the general line that Western civilisation had failed and that some new type of civilisation was necessary to replace it’. This depressed Dulles, who wanted to scuttle the Bandung Conference since it was, he said, ‘by its very nature and concept anti-Western’.18

Coups in Iran (1953) and Guatemala (1954) announced the West’s refusal to allow a new world order to be built. This was followed by a series of coups in Africa (against the people of the Congo in 1961 and of Ghana in 1966), Latin America (against the people of Brazil in 1964), and Asia (against the people of Indonesia in 1965). Each of these four coups produced epicentres of imperialist reaction, with the new military regimes in these countries playing a continental role in suffocating any progressive developments. The coup in Indonesia, which resulted in the murder of a million communists, was almost revenge for Bandung.19

Seventy years on, a New Mood: The Rise of China and the Global South

Seventy years ago this month, leaders of twenty-nine newly or nearly independent Asian and African nations inaugurated the historic Bandung Conference, embarking on the ‘Freedom Walk’ along Asia-Africa Road to the conference’s Freedom Building (Gedung Merdeka) in Bandung, Indonesia. As a diplomatic performance and collective political action, these leaders walked among the teeming crowds to announce that the peoples of the Third World had stood up after centuries of colonialism.

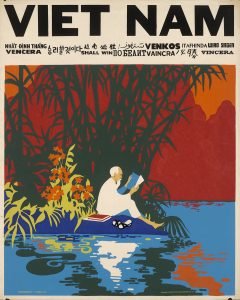

René Mederos (Cuba), Viet Nam Shall Win, 1971. (courtesy: Center for the Study of Political Graphics)

A new world order is slowly emerging, aspiring towards one of Bandung’s core ideas: that international affairs need not be dominated by Western powers. The rise of the Global South has generated new multilateral institutions embedded with the principles of equality and mutual benefit in international relations.

Notably, BRICS has grown in prominence as a platform for the Global South to cooperate – both economically and politically. It has expanded to include five new members – Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran, and the UAE – along several partner states. This new mood is backed by material changes. The centre of gravity of the world economy has shifted eastward, with China and other Asian countries becoming engines of global growth.

By 2023, China was the largest global economy in terms of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) and 47% of its foreign trade was with countries participating in the Belt and Road Initiative – a figure that rose to 50% in 2024, reflecting a deliberate diversification away from Western markets. Likewise, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a multilateral trade pact spanning Asia and the Pacific, has strengthened regional trade ties, with intra-RCEP trade growing by 12% year-on-year. These developments signal a major shift: China is now the largest trading partner for over 120 countries in the world.

As in 1955, China today occupies a central position in this unfolding Global South project –serving as both a target of imperialist aggression and a torchbearer of an alternative path. Nowhere is this dual role clearer than in the global trade war unleashed by the United States, particularly under Donald Trump’s administration. In a throwback to Cold War hostility – employing tariffs instead of troops – Trump began his series of offensives by signing an executive order placing a blanket 10% tariff on all imports into the United States in February. Then, on April 2 – labelled by Trump as ‘Liberation Day’, the US President unleashed a series of punitive ‘reciprocal’ tariffs on 57 countries. These were ostensibly to correct trade imbalances and hit friends and foes alike. A week later, Trump grandiosely announced, via social media, a ninety-day tariff reprieve for countries that ‘have not…retaliated in any way’, while doubling down on China as the primary target with a 145% tariff on all goods.

Amrus Natalsya, Mereka Yang Terusir Dari Tanahnya (Indonesia), Those Chased Away from Their Land, 1960.

Much like Dulles in 1955, the US establishment today fears China’s emergence, which in the past served as an ideological threat as the world’s largest communist Third World nation and is today seen as an economic and existential threat. The tariff onslaught has injected instability into the global economy and further eroded the norms of multilateral trade – ironically undermining the very international trading system that the US helped build in its own favour.

Beijing, however, has refused to bow to this economic aggression. China responded swiftly and resolutely to Trump’s tariff barrage. Within days, the Chinese government announced reciprocal tariffs, zeroing in on sensitive sectors to maximise pressure. ‘We have abundant means to retaliate and will by no means sit by if our interests are harmed’, Chinese officials declared, denouncing Washington’s economic coercion and asserting China’s right to defend its national sovereignty. This stance was met with an outpouring of public support inside China: Patriotic sentiment surged on social media, with the hashtag ‘China’s countermeasures are here’ with 180 million engagements in a week. As one Chinese netizen highlighted, ‘Patriotism is not just a feeling – it is an action’. That China and the Chinese people have stood united against US’ bully tactics carries symbolic significance for the Global South.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Mao Ning, invoking President Xi Jinping’s words from 2018, summed up this spirit of resistance on April 8: ‘A storm may churn a pond, but it cannot rattle the ocean. The ocean has weathered countless tempests – this time is no different’. Two weeks after Trump unleashed tariffs on the world, hitting Southeast Asian countries such as Cambodia (49%) and Vietnam (46%) the hardest, Xi toured the region, signing 31 and 37 agreements spanning various sectors in Malaysia and Cambodia, respectively. In Vietnam, where Xi called on deeper bilateral ties to resist ‘unilateral bullying’, 45 agreements were signed while party-to-party exchanges underscored the alignment between the countries’ communist parties.

Trump’s strongarm tactics and economic warfare dressed as ‘reciprocity’ is the antithesis of the Bandung principles of non-interference and equality. Within this context, South-South cooperation frameworks are receiving increased attention, together with renewed calls to strengthen cooperation and unity within the BRICS, RCEP, and other Global South multilateral platforms. Finding unity among the extreme diversity of the Global South is a tall order. This unity, however, cannot rely solely at the level of states and their leaders, but it must also come from below, from the energy of peoples’ movements and progressive forces across Africa, Asia, and Latin America to revive a true Bandung Spirit against US imperialism and unilateralism. As Zhou Enlai evoked at the Bandung Conference, the hand of imperialism has five fingers – political, military, cultural, social, and economic spheres – which can only be overcome through the unity of the Global South and its peoples.

As Sukarno wrote in ‘Towards Indonesian Independence’ (1933): ‘If the Banteng (bull) of Indonesia can work together with the Sphinx of Egypt, with the Nandi Ox of the country of India, with the Dragon of the country of China, with the champions of independence of other countries – if the Banteng of Indonesia can work together with all the enemies of international capitalism and imperialism around the world – O, surely the end of international imperialism is coming fairly soon!’ One of the major blows against US imperialism was the victory of the Vietnamese people, celebrated fifty years ago.