Why do the Chinese consider Mao as their greatest leader

This will undoubtedly be very surprising to folks who don’t understand China, and/or have only ever been fed clichés about Mao. But if you’ve taken the time to understand Chinese history and how the Chinese view it, it makes perfect sense.

First of all, what makes a great leader in the context of China’s history?

To classify as a great leader in Chinese historical memory, one must typically accomplish several key things.

First and foremost is unification – bringing together a divided China. There were several times in China’s history when the country was divided, from the Warring States period to the Century of Humiliation, and these times always constitute the darkest chapters in Chinese historical memory – creating an almost reflexive aversion to division and a profound respect for leaders who can restore unity.

Which means that, to start with, you arguably cannot possibly qualify as a great leader in the long arc of Chinese history if you haven’t reunified the country. This already dramatically shortens the list of potential “greatest leaders” to just 5-6 figures across all of Chinese history:

– Qin Shi Huang, who first unified China under the Qin dynasty;

– Liu Bang (founding the Han) who rebuilt unity after the Qin collapse;

– Yang Jian (founding the Sui) who first reunified North and South, followed by Li Shimin (as Tang Taizong) who cemented this unity;

– Zhu Yuanzhang, who expelled the Mongols and established the Ming;

– and finally, Mao, who unified China after a century of division and foreign domination.

I obviously exclude here foreign conquerors like the Mongol (Yuan) or Manchu (Qing) rulers, who “reunified” China but under foreign rule.

As an aside, interestingly, among of our list most of those figures have very humble beginnings: Liu Bang was a minor patrol officer who started as a peasant, Zhu Yuanzhang was a former beggar who grew up as an orphaned peasant and even spent time as a Buddhist monk, and Mao was the son of a former soldier who became a farmer & grain merchant in Hunan province.

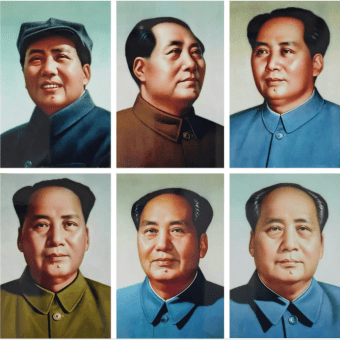

Secondly, the Chinese tradition expects its greatest leaders to be more than just military unifiers or political strongmen. They should also be figures of profound cultural impact who reshaped Chinese society itself. As such, our short list gets even shorter; in fact only three figures from our list truly stand out for their massive cultural impact: Qin Shi Huang, Tang Taizong, and Mao.

Qin Shi Huang standardized writing, measurements, and currency while reshaping the very concept of what China could be as a unified state. Tang Taizong presided over what many consider China’s cultural golden age, establishing systems of governance and cultural patterns that would influence East Asia for a millennium. And Mao, as everyone knows, fundamentally transformed Chinese society, from land ownership to gender relations to education, in ways that continue to reverberate today.

In fact interestingly, Mao was well aware of historical parallels with Qin Shi Huang in this context. In a 1958 speech about breaking with traditional authority (https://marxists.org/chinese/maozedong/1968/4-029.htm), he declared “What’s so special about Qin Shi Huang? […] We’ve surpassed Qin Shi Huang a hundredfold” (“秦始皇算什么?[…] 我们超过了秦始皇一百倍”).

Third, Chinese historical memory particularly values leaders who strengthened China’s position relative to foreign powers and restored national dignity and sovereignty. This is especially true in the modern context, given the trauma of the Century of Humiliation. Through this lens, Mao’s achievement in establishing China as a truly independent power – standing up to both the US and the USSR – takes on particular significance.

And lastly of course there’s the question of lasting impact. While Qin Shi Huang’s dynasty collapsed shortly after his death, and even the mighty Tang eventually fell, the system Mao established – albeit significantly modified by his successors – continues to govern China today. The foundational elements he put in place – universal education, industrialization, women’s rights, national sovereignty, health reforms – made possible China’s subsequent rise under Deng Xiaoping and his successors. This will be the ultimate litmus test of Mao’s “greatness”: how long his “new China” lasts. It’s already 75 years old – surpassing the brief Qin (15 years) and Sui (37 years) dynasties (though still far from the mighty Tang’s nearly three centuries of rule) – and shows no signs of fundamental instability.

Another comparison that’s often made in China is between Mao and Cao Cao, the statesman, warlord, and poet who rose to power at the end of the Han dynasty. Precisely because – very much like Mao – he was all three: renowned for his military, political and literary achievements. The key difference, of course, is that Cao Cao never managed to fully reunify China: he only laid the foundation for the state of Cao Wei which ended the Eastern Han dynasty and inaugurated the Three Kingdoms period.

Of course, to Western observers educated to see Mao only through the prism of cold-war anti-communist propaganda, this perspective may seem jarring. But it illustrates a crucial point about historical memory: how differently the same figure can be viewed through different cultural and historical lenses. While the West tends to focus on the human costs of Mao’s policies – particularly during the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution – Chinese historical memory places him within a much longer continuum of nation-building leaders who transformed their society.

This is not to say that the Chinese aren’t aware of the the complexities of Mao’s legacy or ignore the more difficult chapters of his rule. Unlike Westerners, they lived it… hence Deng Xiaoping’s famous saying that Mao was “70 percent right and 30 percent wrong”, a very common view in China.

Rather, it helps explain why, despite full awareness of all this, many Chinese still genuinely view him as their greatest historical figure. Through the lens of China’s millennia-old civilization, he stands among a very small handful of transformative figures who not only unified the nation but fundamentally reshaped its destiny.

We always say that China thinks long-term, and this is very characteristic of this: the Chinese will typically judge historical figures not through the lens of individual policies or events, but through their contribution to China’s broader historical narrative of civilization, unity, and renewal. In this light, Mao’s achievements become part of a larger story which we in the West typically aren’t even aware of.

This will undoubtedly be very surprising to folks who don't understand China, and/or have only ever been fed clichés about Mao. But if you've taken the time to understand Chinese history and how the Chinese view it, it makes perfect sense.

First of all, what makes a great leader… https://t.co/lgBRNC8eVI

— Arnaud Bertrand (@RnaudBertrand) November 24, 2024

Fun reading for the bunker bookshelf> https://archive.org/details/maos-little-red-book-a-global-history/Mao%27s%20Little%20red%20book%20_%20a%20global%20history/

Beautifully stated, Amarynth. Just my 2 cents worth – although Deng Xiaoping was only in office for a mere 5 years, and as such didn’t gain entry to this exclusive club – in terms of sheer impact in shaping the Chinese brand of socialism, he must be knocking on the… Read more »

thank you, amarynth, for this concise & beautiful summary.