WEST EUROPE BETWEEN 1200 CE AND 1950 CE: THE RISE OF ‘CAPITALISM’ AND ‘COLONIALISM’ & THE MAKING OF ‘CAPITALIST WORLD ORDER’

WEST EUROPE BETWEEN 1200 CE AND 1950 CE: THE RISE OF ‘CAPITALISM’ AND ‘COLONIALISM’ & THE MAKING OF ‘CAPITALIST WORLD ORDER’

Siddhartha Sen

1. INTRODUCTION

The rise of ‘Capitalism’, and advent of ‘colonialism’ are two of the most discussed and passionately debated subjects in the discourses of history, political economy and international politics, nevertheless these are also the topics in which scholars generally tend not to see the wood for the trees. In the mainstream media, readers will seldom come across any insightful essay or analysis that might instigate a thorough discussion on any of these topics (the reporters are almost permanently tuned to consider these phenomena as perpetual one ever since the prehistoric homo sapiens settled for sedentary lifestyle with agriculture and animal husbandry as primary occupations). In the alternate media blog-sites, many analyses and articles appear which directly or indirectly allude to these two phenomena in more detail as compared to the mainstream media. Still, apart from academic research papers and university curriculum, cogent, thorough and simple write-up on this matter that can be understood by the common people, is not an easy task. This essay is an attempt for a thorough and insightful discussion on – perhaps the most significant question of the history of the humankind in the second millennium CE – how capitalism and colonialism morphed into a single entity in west Europe, and spread its wings into the British colonies in North America and Australia, and finally established the ‘Capitalist World Order’, a world-wide system of political economy (which has been also theorized as the ‘World-System’ by a distinguished section of academicians and intellectuals).

While discussing such a contentious matter, it is necessary to identify the objectives, the underlying assumptions, and the boundary limits beforehand as noted below:

- Transformation of the late medieval feudal and semi-feudal economy in different regions of west Europe into capitalist economy took place in multiple stages starting from 13th century. Taking that into consideration, the objectives of this article are to: (a) describe in detail the politics and the economies of a few significant west European powers that were leading the process of transformation from medieval feudal and semi-feudal system to capitalist colonialist system, (b) put forward a hypothesis on the factors that acted as ‘catalysts’ in the process of the making of capitalism, colonialism, and Capitalist World Order, (c) present a hypothesis on the trajectory and final destination of capitalism, colonialism, and Capitalist World Order, and (d) present a hypothesis on the architecture of the foundation of the present Capitalist World Order and how it was constructed over centuries.

- This is not an objective of this article to get into the tale of how capitalism evolved in west Europe from the womb of feudalism through the transformation of the relations of production – after Smith-Ricardo-Marx-Engels, so many renowned liberal Capitalist, Marxist, non-liberal non-Marxist historians and economists discussed, analyzed, and debated the subject in depth, and authored hundreds of seminal books on the ‘transformation processes’ of a feudal-cum-semifeudal economy into a colonialist-capitalist economy in different regions of west Europe, USA, and the world. My focus would be restricted to the identification of the ‘key phases of the transformation’ and ‘influential agents of the transformation’ starting from the germination stage in the medieval west Europe till the maturity in the 20th century west Europe.

- West Europe is the geographical region where it all happened. So, in order to keep this write-up simple, I have avoided paying attention to the relatively low-key events related to the transformation from feudalism to capitalism in east Europe. And, the far eastern borders of Europe where East Slav communities and their contemporaries like Varangians, Khazars, Cumans, and Mongols merged into a relatively new ‘Russian’ identity, for all practical purposes were almost disconnected from the west European economic and political theatre. Even if the east European kingdoms like Polish, Hungarian, Romanian, Bulgarian, Serbian, and Russian had trading interactions with the west European principalities and Asian kingdoms during the medieval ages, they were not anyway instrumental for transformation towards capitalism, colonialism, or Capitalist World Order.

- The most significant assumption, so far as this article is concerned: whenever Jew, Dutch, Anglo, French, Spanish, or any other community is being mentioned, the reader would have to unfailingly consider it as ‘the elites, aristocrats, and oligarchs of the aforementioned community’. That, the top 5% high net worth families of any society control the remaining 95% of the society, has been an established fact ever since the homo sapiens created permanent dwelling discarding the hunter-gatherer life. However, 95% people of a community can’t be held responsible for the deeds and misdeeds of the 5%. And, it must be mentioned categorically, that this essay doesn’t identify the 95% as the motive force for ideologies such as capitalism and colonialism – on the contrary, the underlying assumption is that the 95% population of each of the west European society is ultimately the silent casualty of the application of those ideologies!

Another point that needs to be remembered is: while Anglo, French, German, Dutch, Italian etc. essentially identify the ethnicity and language (irrespective of the religious belief) of the respective community, ‘Jewry /Jewish/Jew’ word signify communities that profess Judaism or Christianity as religious faith and peoples are descendants from any ethnicity like Canaanite (Mizrahim), Berber/Arab/Phoenician (Sephardim), or Khazarian (Ashkenazim). - Ideally, scope of this analysis should include economics, politics as well as culture in detail, for capitalism, colonialism, and final destination the ‘Capitalist World Order’ involve all three aspects of the society (and state). However, due to limitations of time and space, I couldn’t detail the ‘culture’ part. However, that didn’t deter me to mention, while concluding this article, the stellar role played by ‘culture’ for spreading the Capitalist World Order.

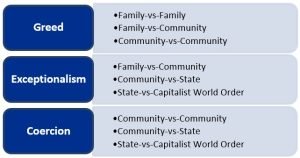

- Why this article only chose the medieval west Europe as the starting point for the journey of capitalism? Don’t we know that, 11th century Song China or 15th century Ming China had many aspects of the Chinese economy that could be termed as proto-capitalist? So, why don’t we accept medieval China as one of the few milestones of that journey? The truth, according to my understanding, is even if the Chinese technology, industry, trade and commerce were well-developed and more advanced than the contemporary west Europe, the Chinese society and state clearly lacked the essence of capitalism and colonialism – ONLY the combination of ‘greed’ for commercial profit (a trait common to traders and businessmen of all communities across the world) and ‘exceptionalism‘ (a socio-political ideology of certain European and west Asian communities) resulted in the rise of ‘capitalism’ and ‘colonialism’. The second factor was simply absent in the Chinese social psyche. Even if the medieval Chinese monetary and banking system were path-breaking, their government lacked the dogma of capitalism – the concept of capital trouncing all other creeds and ideas of human civilization, couldn’t even appear in the Chinese society and state.

- This endeavour is an inquiry into the historical progression of capitalism, colonialism, and the Capitalist World Order associated with it. The author hasn’t kept any stone unturned in order to present a cogent, logical, and rational proposition backed by appropriate historical facts. I have used a lot of relevant quotes from appropriate books and research articles, so that my proposed hypotheses are built on evidences.

Like any other research work, this one is far from being perfect. Even though, I have attempted to raise as many queries as possible, and to seek answer to those queries, it is possible that many more are still waiting to be deciphered. It is also possible, and indeed, desirable that, the readers raise questions on the hypotheses presented in section 5 of this essay.

2. POLITICS AND ECONOMY IN WEST EUROPE DURING 1200 CE TO 1950 CE

This section will be distributed in two sub-sections: brief discussion on the kingdoms and states of west Europe around 1200 CE, and detail analysis of four most significant political and economic entities of west Europe which contributed towards the germination and growth of capitalism and colonialism as well as the making of the Capitalist World Order.

2.1. Political Divisions of West Europe in 1190 CE

Let’s delve into the details of political divisions in Europe (including the geographical regions, the kingdoms and the communities they ruled over) around 1200 CE before the Mongol military forces burst into the vast steppes of east European landmass. The map has been given in Fig 1.1, and details have been tabulated in Tab 2.1. [Link for the map 🡪 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Europe_mediterranean_1190.jpg ; this has been sourced from Perry-Castañeda Library, Map Collection: From the “Historical Atlas” by William R. Shepherd, New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1923].

Fig: 2.1 Europe and the Mediterranean region, 1190 CE

If we take a snapshot of the landscape of Europe during the beginning of 13th century, we would be stunned to find that there was no cultural, social, or political identity of “Europe”. It was only a geographical region which became a melting pot of different Celtic, Latin, Germanic, Viking, Slavic, Turkic, Mongol tribes and their cultures who, for most of the period, were in conflict with each other for political power and wealth. Tentatively Tab 2.1 shows how the European landmass was populated in 1190 CE:

Tab: 2.1 Political division of Europe in 1190 CE

|

Political Entity in 1190 CE |

Compare With the Country existing in 2000 CE |

Majority Tribe/ Community in 1190 CE |

Minority Tribe/ Community in 1190 CE |

|

IBERIAN PENINSULA |

|||

|

Kingdom of Portugal |

Four-fifth territory of Portugal |

Vandal, Alan, Visigoth |

Arab, Sephardim Jew |

|

Almohad Caliphate with capital in Seville, & Córdoba |

Southern region of Spain covering 40% of territory |

Vandal, Alan, Visigoth |

Arab, Berber, Sephardim Jew |

|

Kingdom of Castile |

40% of territory of Spain |

Arab, Berber, Sephardim Jew |

|

|

Kingdom of Aragon |

20% of territory of Spain |

Galatians, Vandal, Alan, Visigoth |

Arab, Berber, Sephardim Jew |

|

Kingdom of Navarre |

|||

|

BRITISH & IRISH ISLES |

|||

|

Kingdom of England (part of Angevin empire) |

England region of the U.K. |

Anglo-Saxon |

Norman Viking |

|

Kingdom of Scotland |

Scotland region of the U.K. |

Scot |

Anglo-Saxon, Norman |

|

Kingdom of Wales |

Wales region of the U.K. |

Welsh |

Anglo-Saxon, Norman |

|

Norman Ireland (part of Angevin empire) |

70% of territory of Ireland |

Irish |

Norman Viking |

|

Gaelic Ireland (Uí Néill in north, Munster in south) |

30% of territory of Ireland |

Irish |

— |

|

SCANDINAVIAN PENINSULA |

|||

|

Kingdom of Norway |

Norway, 10% of Sweden, Iceland, Greenland |

Norwegian Vikings |

— |

|

Kingdom of Sweden |

Sweden, 50% of Finland |

Swede Vikings |

— |

|

Finland |

50% of Finland |

Finn |

Swede Viking |

|

APENNINE PENINSULA |

|||

|

Kingdom of Italy (nominally part of Holy Roman Empire) |

One-third territory of Italy in north |

Latin, Ostrogoth, Lombards |

Sephardim & Ashkenazim Jew |

|

Duchy of Tuscany |

A small region of Italy (1/15) |

Latin, Ostrogoth, Lombards |

Sephardim & Ashkenazim Jew |

|

Patrimonium – Papal States |

A small region of Italy (1/15) in central and north |

Latin, Ostrogoth, |

Sephardim & Ashkenazim Jew |

|

Republic of Venice |

A small region of Italy (1/20), a part of Slovenia (1/3) |

Latin, Ostrogoth, |

Sephardim & Ashkenazim Jew |

|

Kingdom of Sicily |

One-third territory of Italy in south |

Latin, Ostrogoth, |

Norman, Sephardim Jew |

|

Lands of Count of Savoy |

Corsica, Sardinia |

Latin, Ostrogoth, |

Sephardim Jew |

|

MAINLAND EUROPE – WEST |

|||

|

Kingdom of France |

One-fourth territory of France, Flanders region of Belgium, |

Gaul, Briton, Frank, Flemish |

Norman Vikings, Burgundians, |

|

Angevin empire |

50% of France in north and west |

Norman Viking, Gaul, Frank, |

— |

|

Kingdom of Germany (nominally part of Holy Roman Empire) |

Germany, 10% of Poland, Austria, Switzerland, 25% of France, 75% of Belgium, the Netherlands |

Ostrogoth, Frank, Burgundians, Bavarians, |

Saxon, Angles, |

|

Duchy of Austria (nominally part of Holy Roman Empire) |

Austria |

Avar, Frank, Bavarians, |

— |

|

Kingdom of Denmark |

Denmark, southernmost strip of land of Sweden |

Danish Vikings |

— |

|

MAINLAND EUROPE – EAST |

|||

|

Kingdom of Poland |

50% of Poland (except Teutonic kingdoms on Baltic coast, kingdom Lithuanian east of Vistula) |

Poles |

Khazarian |

|

Duchy of Lithuania |

Two-thirds of Lithuania |

Lithuanian |

Poles, Russians |

|

Kingdom of Bohemia and Moravia (nominally part of Holy Roman Empire) |

Czechia |

Czechs |

Slovaks |

|

Kingdom of Hungary |

Hungary, 20% of Serbia, Croatia Slovakia, One-fourth of Romania |

Hun, Avar, Magyar, Cuman, Slovak, Croat, |

Khazarian, Pecheneg, Saxon |

|

Romanian region (west end of Cuman-Kipchak confederacy that had Aral Sea as east end) |

Two-thirds of Romania |

Wallachian, Cuman |

Pecheneg |

|

Kingdom of Serbia |

Two-third of Serbia |

Serb (south Slavic), Avers |

Cuman |

|

Kingdom of Bulgaria |

Three-fourth of Bulgaria, Black Sea coast of Romania |

Bulgars, Avar, Alan |

Pecheneg, Cumans, Romanians |

|

Byzantine Empire |

Greece, 50% of Macedonia, 50% of Albania, Istanbul region of Turkey |

Greek, Roman |

Thracian, Khazarian Jews, Armenians, Bulgar, Slav, Goth |

Note: The eastern borderlands of Europe populated by the East Slavs and other minor tribes/communities are not part of the scope of this research study, hence those have not been included in this table.

Recapitulating the final canvas of the geographical settlement of the major tribal communities who became the dominant socio-political force in their final settlement places in the west and east European landmass by 1200 CE, we arrive at the following four groups of communities:

- The Germanic tribes replacing/absorbing the Latin and Celtic tribes across west Europe

- The Viking tribes replacing/blending with the Germanic and the Celtic tribes across west Europe

- The Slavic tribes replacing/blending with the Celtic tribes across east Europe

- The Turkic tribes replacing/blending with the Slavic tribes across east Europe

A further scrutiny will lead to another conclusion related to the socio-cultural fabric that developed between 900 CE and 1200 CE:

- The Germanic and Viking (and Latin, Celtic) communities got converted into Catholic Christianity

- Some of the Slavic and Turkic communities got converted into Orthodox Christianity

- The West Slavic communities like Pole, Czech, Slovak communities chose Catholic Christianity

- The upper echelon of the Khazar Turkic community chose Judaic religion

The most enduring effect of invasion by the Mongol empire (the largest land empire in the recorded human history) in Europe during the first half of the 13th century was the socio-political reorganization of the east European lands (along with west Asia and central Asia):

- In the vast steppes of east Europe and west Eurasia, the Cuman-Kipchak confederacy (with Alans as an ally) that was built from 1030 CE onward after driving out the Pecheneg tribes (who, earlier expelled the Khazars from the same landmass with the help of Kievan Rus), was completely destroyed by the Mongol warlords. The fearsome warrior Cumans escaped from the Mongol Golden Horde wrath and migrated into the then kingdoms of Hungary, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Byzantium; According to Russian scholars like A.P. Grigorev and O.B. Frolova, Mongol Golden Horde had zones (directly ruled by them) demarcated for administrative purposes – Khiva, Khazaria, Kipchak land, Crimea, Azov region, Circassian Caucasus, Alanian Caucasus, Volga Bulgar region, Walachia. Besides the directly controlled landmass, the Golden Horde also extracted taxes from the East Slavic / Russian principalities like Grand Duchy of Muscovy, Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Pskov, Novgorod, Principality of Smolensk etc. (who established a dependency relationship with the Mongol warlords).

- The Rus Slavic principalities (spread between Ural and Dniester) who after initial onslaught of the Mongol forces was over, accepted suzerainty of the Mongol Golden Horde, built their own areas of influence, and finally coalesced into a kingdom where Orthodox Christianity became the state religion; Alexander Nevsky, a clan member of Rurikid dynasty formed the Grand Duchy of Muscovy, which started as a vassal state to the Golden Horde Mongol Empire, soon absorbed its parent Duchy of Vladimir-Suzdal, Duchy of Tver, Republic of Novgorod, Republic of Pskov, Ryazan, Novgorod-Seversky, and all small principalities by 1522 CE. The Golden Horde collaborated with rising Muscovy Rus till Muscovy Rus denied to pay tributes in 1480 CE. During the long period 500 to 1500 CE, the East Slavic Rus communities and their predecessors and contemporaries like Scythians, Varangians, Khazars, Pecheneg, Cumans, Kipchaks, Mongols merged into a new ‘Russia’ (Russ+Asia) identity – thus, ‘Kaganovich’ surname originated from Khazar ‘Kagan’, ‘Kumanov’ surname signifies a descendant of a Cuman aristocrat, ‘Chaadayev’ family title has been in use by the descendants of Mongol emperor Chagatai Khan. During the 16th, 17th, 18th century Muscovy Rus went on to build the Russian empire (ruling over the central Asian principalities of erstwhile Mongol empire) which hardly could be called as ‘European’, even if, for two centuries – 18th and 19th – the Russian emperors believed so.

- After the Khazar khagans were subjected to repeated assaults by the Kievan/Novgorod Rus and Pecheneg warlords for thirty years after 960 CE, the Khazar Turkic tribes migrated westwards and during the next two centuries, majority of them settled in Polish kingdom, and few smaller groups settled in the lands of Russia and Holy Roman Empire (now Germany) maintaining their separate Judaic religious and social identity. “In 1264, Duke Bolesław the Pious of Greater Poland granted the privileges of the Statute of Kalisz, which specified a broad range of freedoms of religious practices, movement, and trading for the Jews. It also created a legal precedent for the official protection of Jews from local harassment and exclusion. The act exempted the Jews from enslavement or serfdom and was the foundation of future Jewish prosperity in the Polish kingdom; it was later followed by many other comparable legal pronouncements”. [Refer ‘Wikipedia’ 🡪https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Poland_during_the_Piast_dynasty#Reunification_attempts_and_the_reigns_of_Przemys%C5%82_II_and_V%C3%A1clav_II_(1232%E2%80%931305) ],.

Apart from the Mongol invasion, the east European and west Eurasian lands were rocked by an equally far-reaching historical event. In 1204 CE, the Byzantine Empire was invaded, defeated, and dismembered by the military forces of fourth Crusade (drawn from the west European kingdoms financed by the merchants and bankers of the Italian Peninsula). The results were:

- Four principalities arose from the Byzantine empire – Nicaea (one-third of Turkey), Latin kingdom (Thessaloniki region of Greece, and Constantinople region of Byzantine Empire), Epirus (Macedonia, north and central Greece), Achaea (south Greece). Even though the Byzantine Empire was re-established after about 60 years piecing together some of the regions, the reconstructed empire was a pale shadow of its glorious past losing its wherewithal altogether.

- Repeated attacks from the Turkic tribes (Seljuk Turks, Timur’s empire, Ottoman Turks) chipped away the territory of the Byzantine Empire for three centuries before its capital Constantinople was captured by the Ottoman Turk forces in 1453 CE.

- The Ottoman Turk warlords penetrated deep into the east European lands of Orthodox and Catholic Christian kingdoms for another three centuries; in the absence of a well-organized political and military entity like the Byzantine Empire, east Europe was helpless against the formidable military machinery of the Ottoman Turks.

During the early medieval era, the declining Carolingian dynasty which flourished in west Europe between 750 to 890 CE gave rise to 4 – 5 branches each of which established splinter kingdoms across west Europe, each of which in turn fragmented into a number of principalities. As the decentralized power centres multiplied, a socio-political concept came into being in west Europe that has been termed as ‘Feudalism’. A rural estate with a fortified manor building in which the ‘noble’ family i.e., the owner of the estate would live and administer the estate, which would also include a large number of commoners who would toil on the land in the estate for growing agricultural produces and also to produce different kinds of artifacts and items necessary for war. These ‘serfs’ had two types of obligation: (i) to produce enough foodgrains and other food items to support themselves and the family of noble, (ii) to act as soldiers in the army raised by the noble and actively participate in armed conflicts when requisitioned. The ‘nobles’ had four types of duty: (i) to provide agricultural land and security to the people living within the estate, (ii) to provide troops and military gear to his ‘lord’ (who is a ‘vassal’ of king/queen), carry out fortifications, and participate in armed conflicts, (iii) to perform the court duties like rendering advice in council (iv) to pay special taxes i.e., levies due upon contingent events like royal marriages. Apart from the ‘noble’ and ‘serf’/’commoner’ the other class of peoples in the medieval feudalism was ‘clergy’ who led the religious matters and all peoples related to the Catholic Church. Thus, by 1000 CE the socio-political hierarchical architecture in west Europe comprised of three social classes: the ‘nobles’, the ‘clergy’, the ‘serfs’/ ’commoners’. In west Europe, the political and social dynamics during mid-12th century staged quite a few interesting events:

- Consolidation of dynastic monarchies across west Europe – rulers sought to consolidate their authority and hold over political power and the exchequer. These monarchs (such as Henry II in England, Philip II in France, and Frederick I Barbarossa in the Holy Roman Empire) shaped the political landscape of the time. Some of the political framework developed during this period were – (i) bureaucratic systems for running administration and fiscal system, (ii) codification of law that would be used for governance, (iii) control over the feudal vassals, (iv) framework of diplomatic relations.

- The Crusades – the west European military campaigns sanctioned by the Catholic Church had declared aim of recapturing the Holy Land (Palestine) from Muslim rulers, but in reality, it had religious, political, and economic motivations. Actually, the Crusades appear to be the first application of colonialism (by the west European powers). While the European monarchs sought to extend their influence and secure new territories, the merchants and businessmen of the Italian Peninsula wanted to expand their business empire and expand the footprint of their nascent mercantile capitalism around the Mediterranean region.

- Urbanization – it was a key factor of economic growth, as towns and cities grew in size and began to flourish as centers of trade, commerce, and cultural exchange. This led to the emergence of a new social class, the bourgeoisie, comprised of bankers, merchants (existing since ancient times), and artisans, professionals (add-on during Middle Ages). This class was also called as ‘middle class (occupying middle layer between aristocracy as higher layer and peasantry as lowest layer). It played a crucial role in the economic development of society and challenged the traditional feudal order. ‘Bourgeoisie’ word was derived from French borgeis / Dutch burgher both meaning town dweller. However, the Marxist literature defines ‘bourgeoisie’ in a narrow way, as the owners of capital (i.e., the means of production) – essentially the bankers, merchants, industrialists, and owners of different businesses. Guilds and merchant associations were established across different trading towns and cities to protect the interests of various groups of artisans in urban centres, thereby developing organized professional communities. The growing influence of the urban centers led to conflicts with the traditional aristocracy of feudal order, as the bourgeoisie sought to secure their economic and political rights as well as to establish control over the political and governing institutions. The ongoing power struggle between the monarchy and aristocracy on one side and the Catholic Church on the other side now got extended into a three-dimensional tussle with the entry of the bourgeoisie class.

Starting from feudalism during the high medieval era, the history of Europe went through many noteworthy changes in the political, economic, and socio-cultural aspects of life. And, it can be stated further that during the entire second millennium CE, west Europe had unparallel transformational impact on the humankind which, till date has been far beyond the influence dispensed by any other region of this planet in the recorded history of humankind.

2.2. Society, Politics, & Economy in Select Countries of West Europe: 1200 CE to 1950 CE

The following sub-sections peep into the past of a few select geographical regions (that later on transformed into nation-states in the modern era) which became the milestones in the initial journey of capitalism and colonialism, and finally became a part of the foundation of the Capitalist World Order. A brief sketch of the following aspects of the history of those regions have been prepared in sub-sections 2.2.1, 2.2.2, 2.2.3, and 2.2.4:

- Political setup and key historical events

- Economic activities and significant developments

- Scrutiny of select parameters to explore the extent of development of capitalist colonialist economy

- Exploring how colonialism flourished along with capitalism

2.2.1. Society, Politics, & Economy in The ITALIAN PENINSULA: 1200 CE to 1950 CE

Politics: The political history of the Italian Peninsula during beginning of the first millennium is marked by significant political, economic, and socio-cultural transformations. The canvas is dotted with extraordinary events like the rise and fall of powerful city-states, conflict between the papal authority and monarchy, the birth of the Renaissance, the Napoleonic Wars, and the unification of Italy as a modern nation-state. The brief outline of the key events and developments is noted below:

- During the period from 12th to 15th century, the Italian Peninsula was fragmented into numerous kingdoms, principalities, and city-states each governed by its own ruling elite:

(a) In the north – a part of Holy Roman Empire, Marquisates of Montferrat and Saluzzo, Bishoprics of Trent and Bressanone, autonomous city-states of Venice, Milan, Genoa, Mantua, Parma, and Ferrara;

(b) In the central – papal states of Marches and Umbria, autonomous city-states of Florence, Perugia, Urbino, and Siena;

(c) In the south – House of Aragon regions of Sicily and Sardinia islands, kingdom of Naples, and papal states of Benevento.

During the 14th century conflicts like the Wars of Lombardy and the War of the Sicilian Vespers driven by territorial ambitions and power struggles, weakened the states in the Italian Peninsula. The Italic League, an agreement concluded in Venice in 1454 CE maintained balance of power between the Papal States, the Republic of Venice, the Duchy of Milan, the Republic of Florence, and the Kingdom of Naples, as a result of which peace was sustained. All the states thrived economically and culturally (except the two decades following the Black Plague that ravaged Europe from 1347 CE) fostering trade, sculpture and arts.

Renaissance – The elites and aristocrats in the Italian Peninsula yearned for revival of learning and rejuvenation of culture which would bring back the memories of Greko-Roman civilization based in the Apennine and Balkan Peninsulas. The period from 1250 CE to 1500 CE witnessed a renewed interest in classical knowledge, and the flourishing of intellectual and philosophical quests. The renewed interests in study of ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, art and literature led to a new beginning in Europe. Brilliant paintings and sculptures became the hallmark of extraordinary outburst of artistic talents. Scholars, and philosophers engaged in debates and attempted to reconcile reason and faith. Scholars like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Dante Alighieri contributed significantly. Renaissance proved to be one of the greatest milestones in the journey of humankind on this planet!

- In the high Middle Ages, the Catholic Church and clergy became an integral part of west European societies primarily to deal with the ‘spiritual’ matters. However, in reality, the Church became an institution that would firmly get involved in ‘temporal’ matters also. By receiving territorial fiefs from king/duke the Church became one of the largest land-owner in west Europe. The Church with Pope as the head of the institution, during the 1000 to 1400 CE period was involved in operating educational institutions, hospitals, as well as legal courts across west Europe. So, along with the dominance over the religious matters, the Church established itself as the dominant party in (social) governance. Little wonder then, that the Church wanted to also control the political matters in west Europe. This resulted in the Investiture Controversy (conflict between the Church and the state 11th century onwards, over the authority to choose and install bishops of monasteries and pope). The Church-state conflicts grew after the 13th century, with conflict between two factions – Guelphs (Italian supporters of papacy) and Ghibellines (German supporters of Holy Roman Emperor). In the Italian Peninsula, ‘papal states’ became a reality where land under the Church transformed into a state which was ruled by pope. However, with the Reformation movement during the 16th century, the Catholic Church lost most of its temporal authorities.

- During the 16th century, Italy’s political landscape again witnessed upheavals. The Italian Wars, a series of conflicts between 1494 and 1559 CE fought mainly in the Italian peninsula (later expanding into Flanders, and the Rhineland), were primarily fought between the kings of France and Habsburg dynasty (ruling the Holy Roman Empire and Spain). As ‘Wikipedia’ describes it, at the end of the wars, Italy was “divided between viceroyalties of the Spanish Habsburgs in the south and formal fiefs of the Austrian Habsburgs in the north”, and the Papacy remained the most significant Italian power in central Italy. As per the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis on 1559 CE, Corsica went to Genoa, France retained Calais and the Three Bishoprics of Toul, Verdun, and Metz, while Savoyard state in northern peninsula became an independent entity. In west Europe, the ‘Reformation’ movement among the Protestants as well as ‘Counter-Reformation’ movement among the Catholics contributed immensely to the conflicts and warfare during the 16th and 17th centuries.

- During the 17th and 18th centuries, the states in the Apennine Peninsula continued to be under foreign domination – the northern region was under the indirect rule of the Austrian Habsburgs (in their positions as Holy Roman Emperor), and the southern region was under the direct rule of the Spanish Habsburgs, in the central Italy few small but powerful papal states existed due to the influence of Catholic Church (during the Counter-Reformation, the Catholic reaction against the Protestant Reformation). Spain’s involvement in the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648 CE) and the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648 CE) was partly financed by its Italian possessions, and that thoroughly drained the economy of the Italian Peninsula.

Following the European wars of successions of the 1700s, the southern region of Italy passed to a cadet branch of the Spanish Bourbons and the northern region remained under control of the Austrian Habsburgs. Treaty of Utrecht and Rastatt (in 1713, 1714, 1715 CE) passed control of much of the northern and central peninsula (Milan, Naples and Sardinia) from Spain to Austria, while Sicily went to the Duchy of Savoy (and the north-western region of Piedmont). As a result of the Treaty of Hague in 1720 CE, the Duke of Savoy exchanged Sicily with Austria, for the island of Sardinia. In 1738 CE, however, the Spanish Empire regained Naples and Sicily following the Battle of Bitonto.

- Napoleon conquered most of the Italian Peninsula in the name of the French Revolution during the period 1797 to 1799 CE. He set up a few new republics abolishing old feudal privileges, introducing new codes of governance and law, and encouraging trade and commerce. After temporary setback, in 1805 CE Napoleon formed the Kingdom of Italy, converted the Netherlands into the Batavian Republic, and Switzerland into the Helvetic Republic. All these new countries were setup as satellites of the (Napoleonic) French Empire who would make large payments and provide military supports for Napoleonic wars. In 1809 CE Napoleon occupied Rome, and exiled the Pope (who excommunicated Napoleon earlier) first to Savona and then to France. Following the defeat of Napoleon, the Congress of Vienna (1815 CE) redrew the political map of the European continent. In the Italian Peninsula, the Congress restored the pre-Napoleonic patchwork of multiple independent states, directly and indirectly ruled by the prevailing European powers.

After 1820 CE, inspired by the ‘nationalist’ ideas and the desire for independence, various Italian intellectuals and political figures called for the unification of the Italian Peninsula into a single nation-state. Giuseppe Garibaldi, Count Camillo di Cavour, and Giuseppe Mazzini were the key figures in this political movement. Through a series of military campaigns and political negotiations, Italy finally achieved its unification in 1870 CE. King Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia-Piedmont became the king of Italy, and the capital was established in Rome in 1871 CE.

- During the 20th century, Italy experienced significant political changes, including power grab by the Fascist party and participation in both World War I and World War II. Benito Mussolini, the leader of the National Fascist Party, rose to power in 1922, aligned with Nazi Germany during World War II, which devastated Italy and its colonial holdings in northern region of Africa. Italy became a republic through a referendum in 1946 CE, and in 1948 CE a new constitution was adopted. Italy became one of the founding members of the European Coal and Steel Community (the precursor to the EU) which came into force in July 1952 CE, and in 1949 CE Italy became a member of NATO. Due to an economic boom after World War II, Italy became one of the world’s leading industrial nations.

Economy: Economy, and its components – agriculture, industry, trade, and commerce – in the Italian Peninsula underwent momentous changes as the society moved from 1200 CE to 2010 CE.

- The economy of the Italian Peninsula during the 12th to mid-14th century period (before the Black Death) was primarily agrarian, with a feudal system dominating the rural areas with large estates owned by the nobility and worked by peasants. Crops such as wheat, barley, olives, and grapes were cultivated, and techniques like crop rotation and irrigation were practiced. The economy expanded as the merchant class gained prominence, and the Italian city-states became major centers of trade, banking, and manufacturing.

The emergence of the powerful city-states, and the banking families in Venice, Florence, Naples, and Genoa, stimulated trade and commerce and played a crucial role in financing business ventures and facilitating international trade. They controlled maritime trade routes, facilitating the exchange of goods between Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. The merchants engaged in long-distance trade, importing luxury goods like spices, silk, and precious metals. ‘The Cambridge History of Capitalism’ (volume I) mentioned, “At first Sicily and Amalfi were the main foci of trading connections; Genoa and Pisa were the protagonists of the next phase. In the early twelfth century the merchants of the two northern cities pushed their interests towards the eastern Mediterranean and a harsh struggle broke out between them, which was eventually won by Genoa. By this time Venice had expanded its influence over the Adriatic Sea, having by the eighth century already established commercial relations with the eastern Mediterranean. […] While in the Middle Ages the merchants of Venice and Genoa were inextricably linked to overseas trade, the Florentines looked instead to land trade, textile manufacturing, and finance”. Several powerful commercial and banking families emerged in the city-states of the Italian Peninsula who played a crucial role in shaping the economic and political landscapes of their respective cities. As a result, mercantile capitalism appeared on the horizon with its full vigour.

- After the Ottoman Empire occupied Constantinople thereby abolishing the Byzantine empire, the old trade routes from Europe to the East i.e., Asian countries were disconnected. Starting from the end of 15th century through the 16th century, Italian explorers like Christopher Columbus, and Amerigo Vespucci left an indelible mark in the exploration of the so-called “New World” (primarily North America and South America continents, Africa being the other). Generally, the Italian merchants traded goods like textiles, weapons, and other manufactured products in exchange for agricultural commodities, including sugar, tobacco, and cocoa. But, during this period it facilitated the Spanish colonization and empire building in the American continents.

Between the 16th and 17th centuries, the economic centre of gravity shifted from the Mediterranean Sea to the North Sea. The Italian Peninsula went down a long path of decline, though it was not a dramatic one. ‘The Cambridge History of Capitalism’ (volume I) observed that, “The Venetian network shrank and was replaced by Greek and Jewish operators; Florentines reduced their role in western Europe and maintained significant positions in eastern Europe; the Genoese saw a relevant reduction of their control radius as well.”

- The Italian Peninsula faced a period of foreign domination and political fragmentation during this period 17th to 19th centuries CE, with various European powers controlling different parts of the peninsula. Economic activity continued, but it suffered due to the instability and conflicts resulting from foreign invasions. Agriculture and small-scale industry remained the backbone of economy. However, the peninsular bankers and merchants were very much active in the Iberian Peninsula and the Low Countries to promote colonialist and capitalist ventures.

- Italy’s unification completed in 1870 CE marked a turning point in its economic history. The country embraced rapid industrialization, with the northern regions leading the way. Manufacturing and mechanized industries, such as textiles, steel, and machinery thrived, and infrastructure development, like railways, facilitated the domestic and international trade.

The process of industrialization during 19th century brought about changes in the agricultural sector. The advances in machinery and technology improved productivity and efficiency. The large landowners consolidated smaller farms, leading to the concentration of land ownership. Commercial agriculture and specialized production, such as wine, citrus fruits, and olive oil, became prominent. The industrial revolution in Italy transformed its trade patterns. The country became a leading exporter of textiles, machinery, and luxury goods, such as fashion and furniture. Italian emigrants like merchants and bankers played a crucial role in establishing commercial networks around the world, contributing to global trade.

- Post-World War II (20th century): After World War II, Italy experienced an economic boom, also known as the “Italian Economic Miracle.” The country rapidly industrialized, with sectors like automobile manufacturing, fashion, and design gaining international recognition. In the late 20th century, Italy faced economic challenges, including inflation, high public debt, and political instability. However, sectors such as finance, tourism, fashion, and luxury goods continued to contribute significantly to the economy. The Italian economy integrated into the European Union and adopted the euro as its currency, further facilitating trade.

Economy & Politics in Italian Peninsula between 1200 CE and 1500 CE

It is often said that the Italian Peninsula was on the verge of ‘industrial capitalism’ during the beginning of the 1st millennium CE. Finally, it didn’t turn out to be ‘the cradle of industrial capitalism’, however, for agrarian capitalism and mercantile capitalism, it was certainly the place of origin.

Tab: 2.2

|

Economic System & Banking |

|

|

Evolution of Agrarian capitalism |

Aymard observed that by the mid-fifteenth century, the remains of serfdom had disappeared throughout the Italian Peninsula. A stage had been reached in which people could sell their labour freely. Indeed, the expropriation of the peasantry through enclosures – considered as a hallmark of capitalism in the 16th century England – had already begun in Italy in the 13th and 14th centuries. In the wide plains of the Po valley – the most productive land in the Italian Peninsula – capitalist farming became prevalent. Throughout the rest of the peninsula, but especially in the centre, share-cropping was the most widespread form of tenure. The Cambridge History of Capitalism (volume I) commented, “Regarding the control of lords over peasants, northern and central Italy saw an early decline with respect to the rest of Europe. Both peasant and urban communities drastically reduced the power of the lords and their customary rights. This contributed to the separation of land rights from rights over men. Both in Tuscany and the Veneto, feudal institutions were not important and seigniorial rights were quite limited. The presence of fiefs and lordships was significant in Liguria, however. The principal clans of the Genoese aristocracy enjoyed seigniorial rights in the countryside. Lords, however, did not hold full rights over their vassals and – it seems – were unable to prevent them from selling their goods. Apart from some areas – for example in the Sienese countryside – there were no manorial encumbrances on the land. In much of the Italian countryside, nonetheless, the cities imposed their own legislative systems that tended to favour urban property over that of the countryside. In this context, customary rights that rural communities enjoyed over farmland, grazing land, and forests were progressively eroded, at the expense of both citizen property holders and rural elites.” In ‘Rational Capitalism in Renaissance Italy’ published in American Journal of Sociology, May 1980, Volume 85, No. 6, pp. 1340-1355, Jere Cohen mentioned, “the serfs had been freed in Italy before the Renaissance; land was generally divided into smaller estates and was often owned as a business investment by the nobility, the communes, or the capitalists themselves.” |

|

Evolution of Mercantile capitalism |

The Italian city-states tended to specialize in particular sectors, such as Florence with textiles, Venice with shipbuilding, or Milan with metalworking. By 1200 CE, tanners, carpenters, bakers, weavers, metal-workers and almost every other type of craftspeople organized their business around trade-specific associations called as guilds. These guilds tightly regulated production and hence, competition, aiming to protect their members’ interests. The guild system tended to promote small-scale, artisanal production that could be controlled by a small team rather than large-scale industrial production. Jere Cohen noted in ‘Rational Capitalism in Renaissance Italy’, “Guilds, which attempted to set prices, control output, maintain the manufacture of traditional products, and restrict entry into trades, were often very powerful, but were sometimes weak, notably in international trade and banking. This led to the infringement of their rules and privileges and enhanced the influence of market forces. […] Business firms… Branches were commonplace, and bureaucratic chains of command included senior partners, a general manager, branch managers, assistant managers, purchasing agents and bookkeepers, shop foremen, and laborers and garzone.” By 1100 CE, Flanders and Italy were exchanging goods regularly. To encourage this trade, the counts of Champagne in northern France began holding trade fairs. The north European merchants exchanged furs, tin, honey, wool for cloth and swords from northern Italy and silks, sugar, and spices from Asia. To quote Jere Cohen again, “Florence, Pisa, Rome, Genoa, Venice, Siena, Prato, Lucca, and other cities became important trading towns with hundreds of mercantile companies; there were numerous banking firms (over 80 in Florence alone); and while the giant industrial bureaucracies of the 19th century were non-existent, Cox (1959) reports hundreds of manufacturing and processing establishments, employing some 30,000 workers, in the woollen industry alone.” ‘The Cambridge History of Capitalism’ (volume I) commented on the pan-European presence of Italian merchants and bankers as, “We find before us a complex network of family, institutional, and economic ties which were at the base of a gigantic trust composed of thousands of people. Several hundred merchants and firms were scattered across Europe forming the Italian diaspora. This system stretched beyond city walls across a vast area that comprised the Mediterranean, the Black Sea, and the North Sea. The competitive advantages of Italian merchants, that is their capacity to create money of account and transfer it wherever necessary, in addition to their ability to make use of sophisticated credit mechanisms, positioned them within an informal network dominated by family ties and friendships. This undoubtedly facilitated the circulation of both goods and credit, as well as the transmission of economic information. It is worth asking if in this context real market competition could exist. The large commercial and financial markets seem rather to have been characterized by oligopolistic groups that, even when in competition against each other, did not reject cooperation at all, as happened between Genoese bankers in Madrid or between Tuscan and Venetian merchants.” Commenting on the financing of long-distance trade, ‘The Cambridge History of Capitalism’ (volume I) noted that, “The bill of exchange developed in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and it is essentially a promise of payment to a payee and his principal at some future date. It was of great use in long-distance trade and exploited the fact that trading partners in different locations could offset debts and credits. By clearing debt and credit bills locally merchants and bankers could minimize the use of specie, which greatly reduced the risk of theft, apart from the cost of transporting heavy bullion between long-distance markets. Although initially developed by Mediterranean merchants the Italian merchant bankers were instrumental in introducing them to northwestern Europe.” |

|

Presence of the ‘capitalist’ institutions; presence of practices of the ‘capitalist’ system |

The Italian merchants and bankers revolutionized the use of financial techniques between 1200 and 1500 CE. These include business partnerships, holding company, double-entry book-keeping, international giro payments and bill of exchange. In Northern Italy the first bonds were traded, the first private and public banks were set up and the predecessors of the modern company were established. The oldest surviving bank in the world, Monte dei Paschi di Siena which dates from 1472 CE, emerged during this era. The cities of Genoa, Florence and Venice together became the birthplace of modern finance. In support of this view, I quote extensively from ‘Rational Capitalism in Renaissance Italy’ published in American Journal of Sociology, May 1980, Vol. 85, No. 6, written by Jere Cohen: “Although partners added personal cash to the firm to cover debts in crises, and owners’ personal liability was usually unlimited, some forms of partnership did limit liability, notably the acomandz. Conversely, owners’ claims to company assets and profits were determined in advance in the articles of association. Profits and losses were divided according to the number of shares held in the company. While 15th-century partnerships were not joint stock companies they closely resembled them. Joint stock companies, which became a regular feature in 16th- and 17th-century Italy had their roots in 14th- and 15th-century Genoa, where negotiable shares of stock were easily transferable and could be used for collateral or sold. […] “Supervisors and officials in Renaissance firms were chosen carefully: although family and connections played a part (as is still true today in some cases), selection, advancement, and salary generally depended on merit, namely, ability, honesty, and efficient performance. Managers and accountants were trained officials, trained either by schooling or within the firm. […] Italian boys were taught to compute interest and discounts. Officials were trained in correspondence, bookkeeping, and, where there were foreign branches, in a foreign language. […] “The Italians invented bookkeeping, double-entry, commercial law, and marine insurance, were the only ones to use them up to 1500, and maintained their superiority well into the 16th century. Historians agree that other countries, including Calvinist Holland and England as well as Catholic Portugal and Spain, obtained these techniques only insofar as they learned and copied Italian methods. The Fuggers and the Welsers brought capitalist patterns to Germany from Venice, where they were educated. German merchants customarily visited Italy to learn bookkeeping and commercial accounting. The spread of double-entry throughout Europe, which depended on the spread of printing, was aided by Italian textbooks. The Italian writer Pacioli influenced German, Dutch, and English writers on this subject; […] “Italian notaries of the Renaissance era developed and codified commercial or mercantile law, and its rules still form the basis of commercial law today. Notaries drafted deeds and contracts according to legal formulas based on traditions rooted in Roman law. These contracts were legally safeguarded and enforced impartially by local courts, including specialized commercial courts in some cities. Even in their dealings abroad Italian businessmen obtained guarantees of legal rights, impartial judgments, and sometimes even the use of Italian merchant law. (Shakespeare’s ‘Merchant of Venice’ climaxed around a ‘contract’ while depicting a detailed socio-economic profile of Venice – author). “Woolen producers tried to determine the costs of production, including overhead and indirect costs, of each piece of cloth as accurately as possible. The famous merchant Datini test-marketed armour in Spain to see whether profits justified further shipments, Florentine wool producers computed the probabilities of profit and loss, and the pre-estimation of risks was common in moneylending and shipping. Risks were reduced through forming partnerships, branching out to spread the risk, dividing a cargo onto several ships, and buying insurance. “In Datini’s firm, which was not atypical, there were separate books for material costs, petty cash, loans, and salaries, and the firm’s main account book summarized the costs of each separate process and each piece of cloth. […] Benedetto Cotrugli recommended an annual trial balance in Naples in 1458. Trial balances were fully known and in general use at the end of the 15th century; sometimes, especially in Florence and Genoa, they were struck annually, near-annually, or at other regular intervals, although sometimes, especially in Venice, books were balanced infrequently and irregularly … many firms did balance their books to determine profits, losses, assets, and liabilities.” In 1408 CE, the Banco of San Giorgio was set up in Genoa as a banking unit of the Casa – in all probability this was the world’s first public bank that accepted deposits, made money transfers between accounts, and lent money to its account holders. The Banco di San Giorgio was the inspiration for the Venetian Banco di Rialto (1587 CE), which in turn was the example for the Exchange Bank of Amsterdam (1609 CE). Commenting on how the fractional reserve banking system came into existence in the Italian Peninsula, ‘The Cambridge History of Capitalism’ (volume I) noted, “Given the diversity of currencies moneychangers were essential participants in the trading network. They gradually developed banking services when accepting deposits and developing a type of fractional reserve banking as well as services such as transfers between accounts. Thereby payments, both local and international, were made through simple bookkeeping transfers between demand accounts. The primitive forms of fractional reserve banking that developed were predictably associated with occasional failures that alerted the city authorities, who tried and sometimes succeeded in banning the practice for shorter or longer periods”. The Liber Abaci, the Book of Calculations, was published in 1202 CE by Leonardo of Pisa, popularly known as Fibonacci (Fibonacci Sequence for number). He provided calculation techniques for present value, profit sharing, interest rate, and fractions and introduced the Hindu-Arabic numerical of 0 – 9. |

|

The labour market |

The movement of surplus labour from rural agricultural economy to urban economy driven by guilds and unorganised service sectors has been a phenomenon since the medieval era. The Italian Peninsula was no exception. Even if feudal economic forces constrained labour in the rural region before the Black Death, skilled labour made their way to the great urban centres of the peninsula. In ‘Rational Capitalism in Renaissance Italy, Jere Cohen wrote, “The labour market was somewhat freer, despite hiring on the basis of kinship, the importance of independent craftsmen working under guild regulations, and restrictions against foreign workers. Hired wage laborers were commonplace: examples include Florentine industrial woolworkers, Venetian ship crews, and caulkers and smiths, whose guilds were weak. In Florence emancipated serfs formed a formally free labour proletariat, and outside workers were hired to evade fixed guild wages. Workers migrated from town to town when dissatisfied, depending on employment opportunities. It was common for some workers, spinners and weavers, for example, to be chosen on merit. Good workers were often enticed away from competitors to increase profits; for example, skilled brocade weavers, who were in demand, received good wages as an inducement to shift employment.” The Black Death reduced the population drastically, effects of which were felt by both rural and urban centres: the feudal structure was precipitously diminished, and the rising fortunes of mercantile capitalism were grounded. |

|

‘Money lending’, banking and ‘tax farming’ as profession |

Historically, the Christian and Muslim communities were prohibited from lending money at interest by their respective religious scriptures (it would mean taking advantage of the poor, and desperate peoples). The Jewish communities filled in the gap (because their scriptures only prohibit usuary with a fellow Jew) until Protestant reformism cancelled the prohibition on usuary during the 16th century CE. In ‘A Concise Financial History of Europe’ published by Robeco (2018) Jan Sytze Mosselaar wrote about the Italian usuary business, “Two groups of financiers openly charged interest for loaning money, and were socially excluded from society for their usurious activities. The first were the Jews, who could charge interest rates to Christians as they were not regarded as their ‘brothers’. The second group were the pawnbrokers, nicknamed the Lombards, as most of them originally came from the Northern Italian region of Lombardy.” By the 11th century, Jewish moneylending was extensive, and a very important branch of economic activities of the Jewish community. The Christian borrowers, sometimes even the Church would approach the Jew bankers for loans. Nine Cistercian monasteries in England and St. Alban’s Abbey were financed by Aaron of Lincoln. Someone commented ‘The Church regarded Jewish usurers as a morally regrettable by-product of the ban on Christian usury, cities found them a necessary economic corollary, and the more economically advanced countries disregarded the ban (like, Italy)’. Some of the larger merchants who had become merchant bankers, were mostly involved in exchanging money, making them the predecessors of modern foreign exchange (forex) dealers. For this reason, the guild of bankers in Florence was called Arte del Cambio (guild of moneychangers). The huge archive of one of these early bankers, Francesco Datini, has survived until today. Datini, a distinguished merchant in Florence who lived from 1335 to 1410 CE, left us some 150,000 letters, 500 account books and 300 notary letters. His documents give an excellent insight into the early days of modern finance, the use of bills of exchange, the forex contracts. There were no issues regarding availability of ‘credit’ in the medieval Italian peninsula – a free-charge loan to a usurious loan, from a short-term loan to a loan redeemable at borrower’s discretion – traders and borrowers enjoyed wide ranging options. |

|

Public debt |

If city administration council, kings, and emperors wanted to expand infrastructure, or finance a war, which couldn’t be met through regular taxation, they’d either turn to the private bankers and merchants or issue bond (public debt) to arrange the required funds. The earliest form of public debt in Europe was launched in Genoa in 1149 CE and in Venice in 1164 CE. The loans were called compere that were paid off with tax revenues. In 1214 CE, this public debt in Genoa was divided into shares of 100 lire (luoghi in Latin) – these standardized luoghi was the predecessor of government bond in modern era. Two centuries later in 1407, Genoa set up the Casa di San Giorgio in order to consolidate the city’s total debt – all existing comperes were converted into San Giorgio bonds, yielding 7%, and which were transferable. Such consolidation of government debt into a share-issuing institution was the precursor to establishment of the Bank of England in 1694 CE. |

|

Presence of ‘capitalist’ class with concentration of wealth as capital (money and property); Non-Jewish family-owned business houses |

During the medieval era in the Italian Peninsula, several powerful commercial and banking families emerged in the city-states who played a crucial role in shaping the economic and political policies of their cities. A few of them were: 1. The Medici family, particularly Cosimo de’ Medici and his descendants, became one of the most influential and wealthy families in Florence. They were renowned bankers, patrons of the arts, and political leaders. The Medici Bank (pope’s banker) was one of the largest and most respected financial institutions in Europe. It is important to note that the modern form of fractional reserve banking, as we understand it today, emerged during the Renaissance in Europe. In the 15th-century Florence the Medici banks operated on a fractional reserve basis, accepting deposits and issuing loans while maintaining a reserve of a fraction of the deposited funds. 2. The Bardi and Peruzzi families were prominent Florentine banking houses. They enjoyed immense success and accumulated vast wealth through their banking operations, particularly in international trade and financing. A brief description of the Peruzzi family business has been provided as Annexure 1 3. Although not strictly Italian, the Fugger family from Augsburg, Germany, had significant influence in Italian city-states during the Renaissance. They were renowned bankers and merchants, engaging in extensive trade and money lending. The Fugger family maintained close ties with the Medici family and financed several notable figures, including Emperor Charles V. 4. The Pazzi family was another influential banking family in Florence. They competed with the Medici family for power and influence but were ultimately defeated in the infamous Pazzi Conspiracy, an assassination plot against the Medici. 5. The Sforza family rose to prominence in Milan, initially as condottieri (mercenary leaders) and later as rulers. They were successful in consolidating power, and their wealth and influence extended beyond banking into military and political spheres. 6. The Doria family, originating from Genoa, was a powerful merchant family that played a crucial role in the maritime trade and politics of the Mediterranean. They had a strong naval fleet and held significant influence over the Republic of Genoa. 7. The Este family ruled the Duchy of Ferrara and were influential patrons of the arts. While not primarily known for banking activities, their wealth and political power contributed to their prominence. |

|

Presence of influential Jewish families – Sephardim, Ashkenazim – who migrated from west Asia, north Africa, east Europe |

The Italian Peninsula have been a place where Jews (Mizrahim and Sephardim) lived since the first millennium BCE. The Jewish communities were persecuted in the Roman Empire and its splinter kingdoms/principalities – degree of persecution varied from very lenient up to expulsion. ‘Wikipedia’ [Link 🡪 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_Italy ] noted on Jewish presence in the peninsula during the middle era, “The great centres, such as Venice, Florence, Genoa, and Pisa, realized that their commercial interests were of more importance than the affairs of the spiritual leaders of the Church; and accordingly the Jews, many of whom were bankers and leading merchants, found their condition better than ever before. It thus became easy for Jewish bankers to obtain permission to establish banks and to engage in monetary transactions. Indeed, in one instance even the Bishop of Mantua, in the name of the pope, accorded permission to the Jews to lend money at interest. All the banking negotiations of Tuscany were in the hands of a Jew, Jehiel of Pisa.” Some of the well-known Jewish families during the period 1200 to 1500 CE in the peninsula were: 1. The Kalonymos family was a prominent Jewish family known for their involvement in Jewish scholarship and diplomacy. They were influential in several Italian cities, including Rome, Naples, and Amalfi. Members of the family held positions of importance and were often appointed as court physicians and advisors to rulers. 2. The Abravanel family was a renowned Sephardic Jewish family that originated in Spain and later settled in Italy. They were prominent financiers and patrons of the arts. One of the most notable members of the family was Don Isaac Abravanel, a philosopher, statesman, and financier who served as a trusted advisor to various European rulers. 3. The Sarfati family was a distinguished Sephardic Jewish family primarily based in Genoa. They were involved in international trade and finance and played a crucial role in establishing commercial ties between Italy and other Mediterranean regions. Members of the Sarfati family were highly respected and held positions of influence in both Jewish and general society. 4. The Pardo family was a prominent Jewish family that originated in Venice. They were involved in various economic activities, including banking, trade, and money lending. The family had significant connections throughout Europe and the Mediterranean and played a significant role in Venice. 5. The Luzzatto family, originally from Germany, settled in Italy during the 14th century. They were a respected Jewish family known for their scholarship, poetry, and intellectual contributions. Members of the Luzzatto family held important positions in Jewish communal organizations and were influential in the cultural and religious life of Italian Jewry. |

|

Political System, Society & State |

|

|

State apparatus with sizeable population and territory under its jurisdiction; ruling by oligarchy |

During the medieval era, the Italian Peninsula was divided into dozens of sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities like city-state, principality, bishopric, kingdom, papal state, and empire. The city-state like Venice, Genoa, Florence, Milan, and principality like Tuscany, Savoy, and kingdom like Naples had effective administration and strong military. These independent entities vied for power and commercial influence. The absence of a unified central authority made it difficult to establish a uniform policy for governance and economy or to create a conducive environment for large scale industrial capitalism to flourish. However, political and military power was under firm control of the ruling oligarchy (consisting of aristocratic ‘nobles’, wealthy merchants, and bankers). ‘The Cambridge History of Capitalism’ (volume I) described the political architecture in Venice as, “Beginning in the 14th century, the republic of Venice was run by an oligarchy of patricians. This was composed of families with the right to participate in the Great Council, the large assembly that elected the offices of the government. The Great Council also selected the doge, the highest representative of the state sovereignty, who held the office until his death. But the most important government organ was the senate, comprising about two hundred patricians, whose population changed over time. It was the senate that decided major issues concerning foreign policy, trade, finance, and so on. Below the patricians there were the so-called citizens (cittadini), namely individuals who were Venetians either by birth or who had been granted citizenship, who exercised liberal professions, and provided personnel for the bureaucracy. It is important to stress that only the patricians and the citizens had the right to trade overseas; they furthermore enjoyed commercial advantages and privileges in custom duties… Immigrants residing for twenty-five years in Venice could obtain the citizenship (de intus et de extra) by privilege and enjoy the same advantages reserved to nobles and citizens by birth. The commoners (craftsmen, workers, petty traders, and the like) represented the rest of the population.” In ‘Rational Capitalism in Renaissance Italy, Jere Cohen mentioned, “An early 12th-century period of free enterprise gave way to increasing government regulations and restrictions, which included licensing, government ownership, price determination, special trading privileges, restrictions on foreigners, and tariffs. Some cities, for example, Bruges and Venice, were exceptional in permitting free trade and had laws for the negotiation of free trading rights.” |

|

Judicial system |

Due to multiple sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities, the judicial system differed from entity to entity, and within an entity from place to place. ‘The Cambridge History of Capitalism’ (volume I) noted on the complexity of the judicial process in the Italian Peninsula, “The institutions that certified property rights were manifold, because the actors were considered according to their origins and their social status. Men, women, citizens, artisans, nobles, clergy, foreigners, subjects of feudal or ecclesiastical lords, Jews, all had at their disposal specific courts. This legal pluralism consisted of coexisting bodies of law, sometimes conflicting, sometimes complementary. There were state, municipal, and guild courts, feudal and ecclesiastical jurisdictions, customary and merchant laws, each with their own judges. In a framework of deep uncertainty about rights, it was common to turn to the tribunals, to better define the terms of transaction and those same property rights. Nonetheless, it was in this context that some Genoese merchants, in contrast to their Florentine colleagues, preferred to avoid the courts because the judicial system could be inefficient and inadequate to their needs. Main objective was the safeguard of their merchants’ rights, which were regarded as the true pillar of the republic. It is noteworthy that Venetian law forbade tax assessors to use bankers’ records to find out the wealth of taxpayers. The bankruptcy law was severe, and dishonest bankers, even if they belonged to the ruling group, were rigorously prosecuted. Likewise, the Florentine justice system worked quite well.” |

|

Society, culture and religion |

Rome being the seat of Pope, Catholic Christian religion continued to be a central pillar of Italian society during this period. The Catholic Church held immense power and influence, both spiritually and politically. The Papal States, ruled by the Pope, played a significant role in the political affairs of the Italian Peninsula. The Church’s authority was also evident through its patronage of art and architecture. The construction of cathedrals, churches, and the religious artworks flourished as the religious institutions and the religious leaders sought to showcase their spiritual prowess. Religious reform movements, such as the Franciscans and Dominicans emphasized piety, poverty, and service to the common people of the society. One of the most remarkable aspects of the Italian Peninsula between 1200 and 1500 CE was the Renaissance. Italian city-states became hubs of innovative ideas in classical art, sculpture, literature, and philosophy fostering the growth of talents like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. Humanism, a philosophical and intellectual movement that emphasized the study of classical texts, also gained prominence during this time. The revival of ancient Greek and Roman ideas profoundly influenced education, scholarship, and cultural production, ultimately shaping the modern world. The medieval class structure, however, endured with a hierarchical division between nobility, clergy, and commoners. Peasant communities continued to live in rural areas, heavily reliant on agrarian practices. Urban centres, on the other hand, were characterized by a burgeoning middle class engaged in trade and craftsmanship. These social hierarchies constrained the opportunities available to individuals from lower socioeconomic strata. |

What were the political and economic circumstances in Italian Peninsula during 1200 to 1500 CE that were unfavourable for industrial capitalism (if compared with mid-18th century England)?

1) The Italian Peninsula was fragmented in a number of entities which resulted in (i) lack of a single centralized governing authority whose writ would run across the entire territory, (ii) lack of a uniform economic policy that would create a single market (for produces and labour) across the territory, (iii) lack of a uniform legal framework that would ensure ownership of means of production across the peninsula and beyond across generations irrespective of the owners’ religion, ethnicity, and language. As a result of such fragmentation, the Italian Peninsula was at a disadvantage within Europe due to the reduction of the size of the internal market and due to substantial loss of resources in conflicts over the control of external trading network. None of the Italian kingdoms, principalities, papal states reaped the full benefits of economic growth in the other parts of the peninsula;

2) As per ‘Wikipedia’, “The arrival of the Black Death to Sicily has been described by the chronicler Michele da Piazza. In October 1347, 12 Genoese ships from the East arrived to Messina on Sicily. […] According to Agnolo di Tura, the Black Death migrated from Genova to Pisa in January 1348 and spread from Pisa to the rest of Central Italy: to Piombino, Lucca in February, to Florence in March and Siena, Perugia and Orvieto in April and May 1348. Agnolo di Tura described how people abandoned their loved ones whose bodies were thrown down holes all over the city of Siena, but how no one cried because everyone thought that they would soon die as well. […] In March 1348, the plague reached Florence, where it lasted until July.” Black plague devastated the Italian Peninsula in all aspects – social, economic, and political. In an article ‘Pandemics, Places, and Populations: Evidence from the Black Death’ published in 27th Nov’2019, Remi Jedwab, Noel D. Johnson, and Mark Koyama stated, “Some regions and cities were spared, others were severely hit: England, France, Italy and Spain lost as much as 50-60% of their population in just one or two years.”

In the opinion of this author, Bubonic Plage in Europe during 1347 to 1352 CE had an adverse impact which was too radical to be ignored (surpassing all other incidents and factors)! Black Death precipitated the decline of feudalism in Europe. With population down by average 40% there were simply no working-age people who would look for work and employment.

3) In the absence of a unified state, a central bank didn’t get developed in the Italian Peninsula. As a result, there was no coordination between monetary and taxation policies across multiple state authorities. Neither the ‘multiplier effect’ of the fractional reserve banking system could be put to use by the central bank and the state authorities for providing credit to the merchants, traders, and guilds. With the Catholic Church acting as moral guardian, the practice of money creation from thin air by the central bank and earning interest from that, couldn’t become an acceptable economic practice.

4) The socio-economic and socio-political environments were not fully conducive to application of the scientific knowledge in day-to-day life. Thus, world’s greatest polymath, Leonardo da Vinci (April 1452 – May 1519) conceptualized technologically complex machines like a flying machine, an armored fighting vehicle, concentrated solar power, as well as small machines like an automated bobbin winder, tensile strength tester etc. However, such concepts were never developed or tested. Unless scientific knowledge could be utilized for practical purpose, economy couldn’t gain from such knowledge.

5) The Italian city states were involved in colonial expansion of territory and commerce in the Mediterranean region (city-states undertook such initiatives themselves; but a far more interesting attempt of indirect colonization could be noted as the merchants and bankers of the peninsula funded the crusades), but those were not very consequential in terms of scale, hence its merchants and bankers (i) lacked opportunities of profit accumulation driven by slave-operated plantations and mines, (ii) lacked foreign lands from where raw materials could be sourced and finished goods could be marketed (both of which were part of colonial empires built by the well-known countries of west Europe);

6) The merchants and bankers in Italian peninsula were divided into different communities on religious lines – Catholic Christian (mixture of Latin, Ostrogoth, Lombard, and other Germanic communities) and Jew (Mizrahim, Sephardim) – as well as different professional lines – different guilds built on the basis of industrial sectors – long before other European societies experienced that. However, few significant characteristics were (i) out of many wealthy merchant-banker families, no single group of ‘oligarchy and aristocracy‘ coalesced to present a powerful and resourceful lobby, (i) the Christian and Jew wealthy families didn’t establish marital relationship that would merge their economic and political interests, (iii) the Christian and Jew wealthy families couldn’t become the undisputed top layer of the social hierarchy which was also dominated by the Italian renaissance elites (artists, scholars, patrons) with multifaceted personalities, (iv) the wealthy merchant and bankers were not pursuing business with single-minded devotion, they had to also (partially) fund the humongous initiatives of architecture, sculpture, and art – Italian renaissance – that continue to bewilder the world even now!

7) The Italian Peninsula had relatively limited natural resources. The scarcity of resources, such as metals, minerals, coal, and other energy made the overall economic environment somewhat immune to large-scale industrialization. However, manufacturing of glass for which the required raw materials could be easily sourced, was abundantly practiced.

As a result of the above-mentioned factors, even though the Italian city states and kingdoms had a strong economy based on mercantile capitalism and agrarian capitalism (that co-existed with the feudalist mode of production in agriculture), a conducive environment for further transformation into slave capitalism (as practiced during the 16th to 19th century west Europe) or industrial capitalism (as blossomed during the 18th century onward in west Europe) was absent.